Manaslu – ski descent: A story of a ski descent at 8,000m, without oxygen nor sherpa support

Manaslu Ski Descent – The Journey

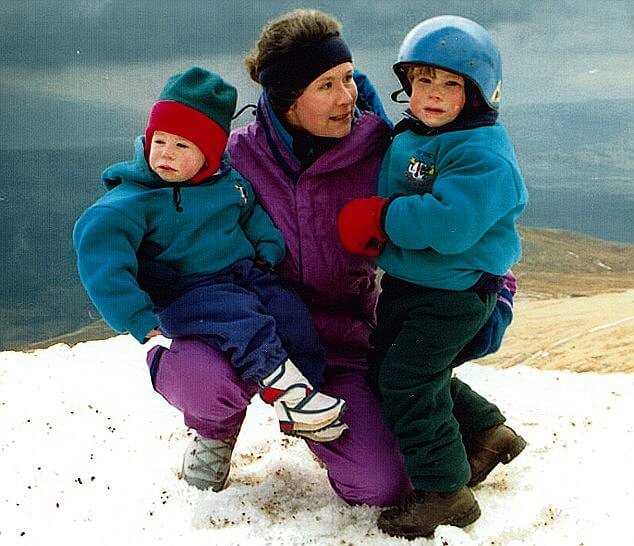

After a few months of procrastinating and getting my life back together, I’ve finally come around to writing a brief trip report of my climb and ski descent of Manaslu, an 8200m peak in the Himalayas. I completed this journey without a sherpa, sans oxygen and alone (sort of?). The approach was from Uzbekistan to Pakistan, carrying all my equipment on my bicycle. That story is for another time 🙂 however, this was my bicycle setup through the Karakoram and the gear I ultimately used on Manaslu.

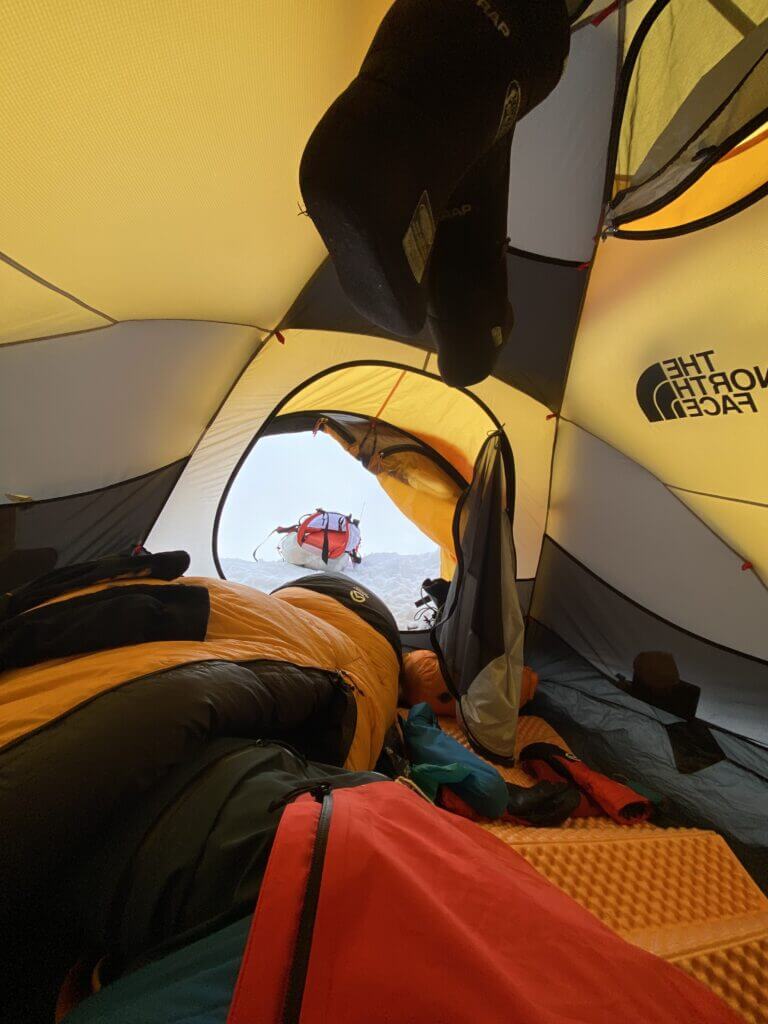

The bike felt heavy, but I was as MINIMAL as possible. For example, I decided I would have to get by with only a +20F bag on an 8000m peak if I wanted to pull this off. This meant a tricky strategy and a push from Camp 2 at 6400m to the summit at nearly 8200m. On top of that, I was carrying the bare necessities. After several months of bicycle speed, testing my setup on 7000m+ peaks, various hardships & mishaps (there was some joy!) I gave up the bicycle near Gilgit, Pakistan and booked a flight to Nepal from Islamabad with my limited gear, forcing me to climb in a very minimalist fashion. Before this climb, I found little information online, so I hope this trip report can be beneficial for others, whether you are climbing with or without support.

What you need to do to climb Manaslu

I started in Kathmandu, contracting with a company named ‘Satori’. This is a basecamp+ service company, assisting climbers with logistics and any other support they need. Unfortunately, the Nepalese government will generally not allow you to climb completely independent for an entire climb, forcing climbers to hire ‘base camp services’. While I’m sure it benefits the local economy, these services are quite cushy and overpriced. They include an army of porters to basecamp, basecamp cooks, basecamp tents, teahouses on the trek in, fixed lines (critical service imo) etc. Ideally, I would’ve liked to climb Manaslu completely unsupported, but found it was damn near impossible. Plus, being solo, I really wanted to use fixed lines across the crevasses. In the end, I was happy with what I got… an incredible experience with some safety.

The cost was nearly prohibitive since I funded it all on my own dime… At least it was cheaper than Cho Oyu eye roll. Cho Oyu is technically easier and maybe safer, but closer to $15,000USD in a very minimal package. I paid roughly $7500USD for the package on Manaslu, which included all the normal basecamp services, plus my permit.

With a sherpa and oxygen, you can expect to pay around $12,000USD. With a guide, I don’t care to even think about… Probably around a hefty $20,000USD. Turns out, Nepal also charges a ‘heli ski’ permit for any skier on the mountain. Clearly, they have no understanding of the concept of ski mountaineering, as no helis were used. This was extremely frustrating, as the extra permit was $1500. A bit mind-boggling, as I consider my skis a safety tool to climb at that altitude without oxygen. Should the government also charge for a ‘heli mountaineering boot permit’?! In the end, I managed to find a way to split the ski permit price sharing with the Bulgarian and an unknown/unseen Chinese skier (??), in which the cost was reduced by a third. Yay.

Day 1:

Starting in the classicly dirty and chaotic Kathmandu! There, I met the team and sorted out all the permits. The other climbers were pretty cool, a badass French Woman named Elizabeth Revol, a Canadian named Sebastian, two Italians named Angelo and Davide and a charismatic Bulgarian named Vladimir Pavlov (with a snowboard)! They made great conversation and were themselves pretty inspiring individuals who told great stories. They would become great friends of mine by the end of the journey. All members seemed pretty dialled with their training and fitness, I was impressed. Turns out, not all Himalayan climbers are high paying clients with limited experience… Surprise!

Day 3:

After a few days putzing around Kathmandu, we took a long jeep ride (10+ hours) to the first drop off point, Besishahar. This tiny village was on the start of the popular Manaslu & Annapurna circuit, so it had all the amenities, it was quite comfy. Being previously acclimated from my bicycle journey, the next task was a slow plod to basecamp during the rainy season. To keep me sane and fit, I would go trail running in the evenings. The other climbers were not acclimated to the same standards, so some struggled a bit at Larke La (pass) 5100m.

The trek was mostly uneventful and without views (rainy season approach), answering questions from curious trekkers and bonding with my base camp team. The clientele we met heading for Manaslu was sometimes a bit baffling…. Mostly undertrained and well-off people, with the dream of climbing an 8000m peak. Naturally, everyone claims they will be doing an oxygenless attempt, but in reality, only about 2% make it to the top without oxygen, and most have sherpas carrying their equipment. I tried not to pass judgement, but I felt too many people had unrealistic fantasies (maybe mine were as well?) A few rainy days later, we crossed over Larke Pass and into Samagoan, the city below basecamp. Here, we had our first blue skies and view of the mythical Manaslu!

Day 8?:

Once we arrived at base camp, we were given our base camp tents, excellent meals and introductions to the entire base camp team. Everyone was friendly, but I found the sherpas to be quite apathetic towards the westerners. Don’t get me wrong, they were great people in the end…. But you got the vibe that they really did not care for outsiders. Maybe for a good reason? Maybe not. They were curious about my skis, so at least it kept them entertained. The sherpas found it amusing and terribly dangerous that someone would carry up skis to the summit of an 8000m peak. I tried my best to explain that skis were safe, with no luck. At one point, I built a ski track around basecamp and had some sherpas try to ski for the first time! Hilarity and laughter ensued.

Basecamp was virtually a small city, with hundreds of tents, Wifi(!!!), trekkers, cooks, sherpas, porters, and dogs. Privacy was rare, but the setting was stunning. Most often, it was cloudy above basecamp, although we got the occasional rare glimpse of that beautiful Himalayan range.

The other climbers from Satori arrived by helicopter, a group of 7 Italians, 3 Andorrans and an Australian. From the start, I knew most of them were not going to make it. They seemed competent enough, however, flying into basecamp is a shitty strategy, and it is not recommended it. It’s also a super lame style to climb the mountain, sorry to burst some bubbles.

These climbers were punished for their lack of time commitment, and rightfully so. All except 3 managed to get sick (no summit), and one lived in a refugio in the Dolomites. The other Andorrans were fit & experienced enough to push through… Although one had a serious case of HACE and had to be sent down with oxygen. He actually almost died at Camp 4. I understand that not everyone has the luxury to take a month off to climb an 8000m mountain… If this is the case, just don’t! End rant.

I went up to camp 1 the next sunny day to stash some gear and my tent, it was a chore to carry everything. However, the glacier was well filled in at the time, so I really enjoyed the skiing back down. Usually, I could beat the standard descent times by several hours with the skis, minimizing my time in the hottest part of the day. I really enjoyed taking turns with my new snowboarding buddy, Vlad.

The next step was to wait for our ‘Puja’ ceremony to end, in which the monks come up to basecamp in order to ask the mountain Gods permission to climb. The rule is to stay below camp 1 until the Puja ceremony was over. This probably helped a lot of people with acclimatization, but to those who were acclimated, we had to wait, respect the culture and hold off on moving forward.

Day 13?:

After Puja, we were free to go. The climbers with Sherpas were stuck for a few days, but the independents moved on. I found the higher route on Manaslu to be quite straightforward and minimal in hazard, minus a few sections above Camp 1. The icefall from C1 to C2 is indeed dangerous… Filled with hidden crevasses, hang fire, and slow climbers. At least the ladders were exciting.

I tried my best to gun it through these sections but was often finding myself behind a horde of slow and out of shape clients. It was stressful, as you knew any seracs above were coming down on the route if they decided to blow. The range of fitness and style can be a bit insane at times. For example, the Chinese teams generally lay siege to the mountain, and typically start taking oxygen as low as C2!!! Other clients are basically spoon-fed by their sherpas, while some climbers tend to require minimal assistance. Lots of flavours in the Himalayas.

Once at C2, I set up my final camp and skied back down to basecamp, skiing through most of the icefall and lower slopes. After a few days of stormy weather and rest, I went back up to C2 to sleep for a few days and acclimate. C2 is around 6400m, so I couldn’t tolerate sleeping for long. Often I would spend 2 days max, going up to C3 to ski the mellow powder slopes. C3 is only a few hours from C2 and 400m higher, so I never felt the need to haul my gear up there. The skiing was usually fantastic and the climbing was mellow. Below is a rough route overview, with the most dangerous hazard from C1 to C2.

My plan of attack was to go from C2 to the summit and back down in a single push. Most people told me this was impossible, as it was nearly 1800m (6000′) to the summit, but I felt confident and also that it was my only option to avoid getting too sick, too cold or bogging myself down with weight. I had trained hard and tested my strategy in various ranges around the world. The ability to skip camps is a blessing, not a curse. In my opinion, sleeping high is the real killer. I spent a lot of time between C3 & C2, just walking around and searching for lines. As a bonus, Camp 3 was usually above the cloud deck and afforded beautiful views of Manaslu.

Day 20ish?:

Finally, after a few weeks of acclimatizing and skiing, we started to get our first instincts that a summit window was approaching. Summit window in the post-monsoon Himalayas is tricky. It’s a balancing act between storms, crevasses, snow, winds, temperatures and avalanche stability. If you go to early, you are risking some serious post-holing, cold temps and epic storms. If you go too late, the crevasses are a mess and you risk being up high during a jet stream event… Not quite ideal on the summit of one of the tallest peaks in the world.

There was a larger percentage of sunny days, the winds were dissipating, and the snow was consolidating. Overall, looking good on the mountain. I felt pretty good about my health, so I was ready to go. Unfortunately, I jumped the gun a little too early and went to C2 with 3 days until the ideal summit push. I couldn’t stand sleeping at C2 after day 2 and tucked my tail between my legs and skied back down to basecamp.

Thinking I let my impatience get the best of me, I was bummed. Luckily, there was a 3-day summit window, so my new plan was to rest for a day in basecamp, and go straight to the summit once I reached C2 again. After a full day of rest & recovery, I went from basecamp to C2 and tried to keep myself as healthy as possible before the ascent, with the plan to start moving towards the summit at 10 PM. With little sleep, I packed my gear and started making my way up.

The start from C2 was cold and snowy, I knew the route well to C3, but I was post-holing and breaking trail, which was incredibly frustrating. Once I made it to C3 and could make out the other tents, I started moving up the ridge to C4. At this point, the snow was knee-deep and I was yet again breaking trail. I contemplated turning around, as I knew I couldn’t reach the summit in the current temps and exhausting trail breaking.

However, I had the assumption that things would change once I got to C4, which I was very fortunate that they did. On the way up, I found a headlamp buried in the snow…. To my surprise, it was a lone & obese Japanese climber on the brink of death. He was incoherent, purple and clearly exhausted. There was absolutely nothing I could do, except notify sherpas when I got to C4. Turns out, this guy survived! I suspect he had no business being on the mountain. From C4, shit hit the fan for me. C4 sits at a ridiculous 7400m…The sun was rising, but I was feeling the altitude at this point and seeing the other climbers and sherpas with oxygen didn’t help my cause. Around 7300m, the altitude really starts to kick my ass.

Video of Camp 4, from my friend Sandro, who carried two drones up the mountain! I believe he crashed one… Free drone if you’re willing to explore! 🙂 Camp 4, Manaslu.

The thing about supplemental oxygen is that it puts that mountain on a completely different playing field. An 8000m peak becomes a 7000m peak. While still difficult, the degree of difficulty without oxygen is several magnitudes in difference. Oxygen using climbers could maintain a steady pace, smile, talk, and perform tasks reasonably. They were happy. I felt like I was in a different world. Speaking was difficult, I was terribly cold (even in reasonable temps), and I was not stoked. My pace was roughly 100-200m vertical per hour…. barely snail speed. The words of encouragement from climbers descending only made me more upset, as they didn’t seem to grasp the hell I was experiencing. I knew they meant well, but it’s hard to stay positive being so oxygen-deprived. In the end, I gritted my teeth and kept plodding forward.

As I was climbing and nearing the summit, small storms were rolling in and then fizzling out to beautiful bluebird conditions. It certainly gave me anxiety, but I kept faith that the storms would stay small and dissipate. The last 100m felt nearly impossible, I can recount 1 deep breath for every 10 steps…. Brutal.

Finally, I reached the summit plateau alone & in poor shape… I was exhausted and ready to be off the mountain. Plus, it was cloudy, cold and miserable. After this experience, I had more respect for the “Death Zone”. On top, there was still another 50m exposed traverse to reach the top. Ugh. I sucked it up and put one foot in front of the other, utterly exhausted. I was being extra cautious as to not fall on the exposed traverse into the void. Once I reached the summit, I took a quick break and can recall my mental state… Not good. I was definitely in a place I did not belong. This only meant one thing: Time to ski! 🙂

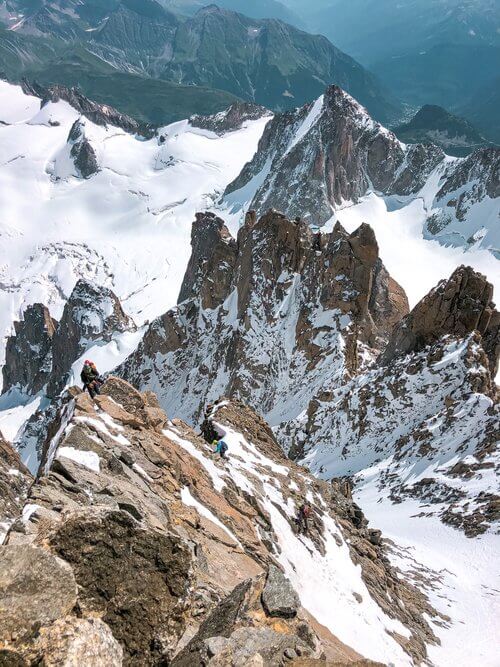

Being alert & alarmed with my state, I clicked on my skis and started wheezing down the slope in between very noodly S turns. My legs were fried beyond frying. Finally, I felt the oxygen surging back into my bloodstream and my focus came back rapidly. I must’ve been below the death zone once again. I could finally ski the mountain as I wanted, so I started opening things up. Sure enough, about 400m off the top, I hit a buried fixed line… Sending me into a triple summersault in powder. I was livid at the situation. My first thought was ‘Anthony, get your shit together… NOW. Don’t blow it on the descent’. After recollecting myself, I skied smoothly and confidently on the mellow slope until I reached C4, where I felt home free! Lots of cheering from Camp 4 had me stoked.

Vlad on the ski descent from near the summit (not my video): Snowboard Descent from near summit

This wasn’t the end of my adventure, however. The climbing route is NOT a skiing route… littered with buried oxygen bottles, fixed lines, ice bulges, and generally bad snow. I decided to traverse skiers left to the massive 40-45 degree snow slope above C3. While conditions were whiteout, I could make out tracks from my Bulgarian snowboard buddy down the face.

Vladimir had skied off the summit earlier and we had both scoped out the line a few days prior. I followed his tracks until they disappeared. Since I had seen the face before, I had confidence that I could open up the face without any hazards. It was some of the best skiing I had ever done! A massive 2000′ face of knee-deep powder. I couldn’t believe the setting I was in. There was a concern of instability & I had to manage some sluff, but otherwise felt conditions were stable and good. Stoked!

Video of Vlad on the snowboard descent from C4: Snowboard Descent C4-C3 Headwall

Finally, I made it to C3 and opened it up further to C2, whooping and hollering, although the snow had turned into mashed potatoes and gravy. At C2, as I was packing up and eating, I managed to fall asleep in my sleeping bag, mid snickers bar. Looks like I wasn’t making it to basecamp for dinner… Oh well 🙂

I woke up the next morning to bluebird conditions, admiring the mountain and my ski tracks down the face. I was elated and very satisfied. A few hours later I reached basecamp, sunburned, haggard, and exhausted. I was greeted with cheers from my basecamp teammates and the sherpas. Everyone was happy that I skied off the summit safely and we were celebrating successful climbs coming from everyone! Good food and rest couldn’t come soon enough.

After a day or two of rest, my time on Manaslu came to an end. Nearly everyone except the sherpas and porters takes a heli back to Kathmandu. Since I had no time obligations, it was time to enjoy my newfound superpowers as Red Blood Cell Man! I decided I would run the Manaslu circuit, Annapurna Circuit, Annapurna Sanctuary, and Everest 3 Pass Trek + Basecamp. It was the best few weeks I had of running and celebrating. Since the monsoon was gone, I enjoyed shorts & t-shirts and running through some of the most epic scenery imaginable. A few shots from trail running the classic circuits:

Overall, my time spent in Nepal was amazing. I enjoyed nearly every minute and tried to get the most out of my time there. I met some incredibly inspiring people, pushed myself in ways I never thought were possible and learned a lot about myself. Obviously, there is a lot more I could write about this, and so many more stories. One day I hope to document more, but this is as far as I get for now! I hope you’ve found this trip report informative, inspirational or mildly entertaining. If you have any questions, feel free to reach out. Thanks for reading!

Gear List for a ski descent at 8,000m, on Manaslu

- Boots – Fischer Travers Carbon (Not oversized)

- Overboots – 40 Below

- Skis – Salomon MTN Explorers 88 – 170 length

- Bindings – Plum 150 AT Binding

- Poles – Whippet & BD Alpine Cork

- Sleeping Bag – Western Mountaineering, Alpinlite (+20F Rating)

- Booties – Western Mtneering

- Crocs (The most essential piece of gear on the planet)

- Tent – Rab, Latok 2

- Shell – Rab Windshell

- Hydration – Platypus, Softshell Flask, 1L

- Shovel – Climbing Technologies Axe/Shovel Combo

- Hydration – Ultralite Nalgene, 1L

- Baselayer Top – Rab 150 Merino Half Zip

- Baselayer Bottom – Smartwool Midweight

- Hat – Arcteryx Cap

- Midlayer – Patagonia R1

- Puffy – Arcteryx Cerium LT

- Midlayer – Rab

- Softshell – Ortovox

- Stove – MSR Reactor with 1L Pot

- Pack – Hyperlite Mountain Gear 45L, Porter with Modified Ski Strap

- Garmin InReach Mini

- Gloves – OR Alti Mitts & OR Alti Gloves

- Socks – Midweight Smartwool

- Goggles – Julbo Aerospace

- Sunglasses – Julbo MonteBianco w/ Sideshields

- Harness – BD Couloir

- 1 Prusik

- 1 Alpine Sling

- 3 Locking Caribines

- Ascender – Petzl Micro Traxion

- PAS for Ascender Extension

- Crampons – Singing Rock, Strap version

- 1 Petzl Lazer Speed Icescrew

- 2 Buffs