Mount Everest, revered as Sagarmāthā in Nepali, Chomolungma in Tibetan, and named 珠穆朗玛峰 (Zhūmùlǎngmǎ Fēng) in Chinese, stands as the apex of our planet, the zenith above sea level. Nestled within the rugged contours of the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas, this formidable peak serves as a stark and magnificent reminder of nature’s supremacy, with the China-Nepal border slicing across its icy crest. An elevation of 8,848.86 m (29,031 ft 8+1⁄2 in), affirmed in 2020 by Chinese and Nepali authorities, underscores its stature as Earth’s highest summit.

Notwithstanding its grandeur, Mount Everest is an emblem of both the allure and the perils inherent in high-altitude mountaineering. Its towering heights draw a spectrum of climbers, from eager amateurs to the most seasoned mountaineers. Two chief routes challenge these adventurers – the “standard route” hailing from the southeast in Nepal and its counterpart emerging from the north in Tibet. While the standard route does not present major technical challenges, climbers must confront and endure altitude sickness, capricious weather and wind conditions, and risks from avalanches and the notorious Khumbu Icefall. As of 2022, the mountain has claimed the lives of 310 climbers, with over 200 bodies still tethered to its treacherous slopes.

The narrative of the human endeavour to conquer Everest begins with British mountaineers, who, restricted by Nepal’s closed borders, pursued the summit from the north ridge route on the Tibetan side. From the initial reconnaissance in 1921, the British expeditions gradually scaled new heights by reaching 7,000 m (22,970 ft). The 1922 expedition marked the first time a human climbed above 8,000 m (26,247 ft). This saga of resilience and exploration further deepened with the 1924 expedition, embedding one of Everest’s enduring mysteries – the fate of George Mallory and Andrew Irvine, who vanished during their final summit attempt.

It was only in 1953 that the peak was definitively conquered, with Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay ascending the southeast ridge. Norgay had previously reached 8,595 m (28,199 ft) with the 1952 Swiss expedition. The Chinese mountaineers, Wang Fuzhou, Gonpo, and Qu Yinhua, etched their names into the history of Everest as the first to ascend from the north ridge on 25 May 1960. This storied history and the rugged allure of Mount Everest continue to beckon adventurers from around the globe, challenging them to pit their mettle against its icy grandeur.

General outline

- Mount Everest: Names and Legends of the World’s Highest Peak

- Beyond the Summit: Surprising Facts About Mount Everest’s Height

- Conquering the Roof of the World: Historic Expeditions

- Conquering Everest: Challenges and Triumphs Across Seasons and Altitudes

- Everest Commercialization: Costs, Controversies, and Challenges

- Extreme Everest: A Playground for High-Altitude Sports

- Environmental Crisis: Impact of Commercial Climbing

- Everest’s Ecosystem: Flora and Fauna at High Altitudes

- Climate and Meteo on Mount Everest

Mount Everest: Names and Legends of the World’s Highest Peak

Famed as the highest peak on Earth, Mount Everest is known by various names across different cultures. Among these, the Tibetan moniker Qomolangma or Chomolungma, meaning “Holy Mother”, holds historical prominence. This name was first transcribed in Chinese in the Kangxi Atlas during the reign of Emperor Kangxi, in 1721, making its Western debut on a 1733 Parisian map by French geographer D’Anville.

In Chinese, the majestic peak is formally known as 珠穆朗玛峰, with the pinyin transcription reading as Zhūmùlǎngmǎ Fēng. While alternative Chinese names like Shèngmǔ Fēng (“Holy Mother Peak”) have existed, a 1952 decree from China’s Ministry of Internal Affairs consolidated the use of a single name, favouring the official transcription.

However, the narrative of Everest’s name is intertwined with colonial history, largely influenced by the British survey’s intent to uphold local nomenclature, as seen with peaks like Kangchenjunga and Dhaulagiri. The British Surveyor General of India, Andrew Waugh, found this endeavour challenging due to the exclusion of foreigners by Nepal and Tibet, alongside the multitude of local names. Waugh proposed naming the peak after his predecessor, British surveyor Sir George Everest, resulting in the title “Mount Everest” being officially adopted by the Royal Geographical Society in 1865, despite Sir George’s objections. Intriguingly, the contemporary pronunciation of “Everest” deviates from Sir George’s original pronunciation of his surname.

In the 1960s, the Nepali government introduced the name Sagarmāthā, translating to “goddess of the sky” or “the Head in the Great Blue Sky”. This name draws from सगर (sagar), meaning “sky”, and माथा (māthā), meaning “head”.

Other historical names include “Deodungha” (“Holy Mountain”), “Peak XV”, and “Gauri Shankar” or “Gaurisankar”. However, the latter has since been associated with a different peak approximately 30 miles away. The myriad names of Mount Everest reflect the cultural diversity and historic complexity surrounding this towering peak, each narrative adding another layer to its enduring allure.

Beyond the Summit: Surprising Facts About Mount Everest’s Height

Though renowned as the world’s highest peak, Mount Everest, straddling the borders of Nepal and Tibet, doesn’t claim every superlative in the record books. Its summit, towering at 8,849 meters (29,032 feet), indeed holds the title for the highest point above global mean sea level, the average elevation of the ocean’s surface used as a baseline for measuring heights. Yet, intriguingly, Everest’s pinnacle does not stand as the point farthest from Earth’s centre.

Our planet, contrary to the perfect sphere we often envision, exhibits a subtle bulge at the Equator due to the centrifugal force generated by its constant rotation. This equatorial protuberance means that the peak of Ecuador’s Mount Chimborazo, located just one degree south of the Equator, is actually the highest point relative to Earth’s centre. While the apex of Chimborazo only reaches 6,268 meters (20,564 feet) above sea level, its position on the Earth’s bulging midriff situates it over 2,072 meters (6,800 feet) farther from the Earth’s heart than Everest’s summit. As a result, Chimborazo enjoys the unique distinction of being the closest terrestrial point to the stars.

Further confounding common perception, Everest does not constitute the tallest mountain on Earth. This accolade goes to Mauna Kea, a majestic volcano nestled on the Big Island of Hawaii. Originating from the depths of the Pacific Ocean, Mauna Kea’s grandeur emerges as it ascends over 10,210 meters (33,500 feet) from base to summit, offering a distinct perspective on our understanding of “height” and “tallness” in the geological realm.

Conquering the Roof of the World: Historic Expeditions

Boasting the highest summit on Earth, Mount Everest stands as an enduring testament to the human spirit’s relentless quest for exploration and achievement. Its commanding stature has consistently drawn the gaze of adventurers and mountaineers, eager to etch their footprints on its icy slopes. The question of whether the peak was surmounted in ancient times, however, remains shrouded in the mists of history, with no definitive evidence to support or refute such ascents.

The allure of Everest reached a poignant climax in 1924 during a daring attempt by George Mallory and Andrew Irvine to reach the elusive summit. Their expedition, steeped in intrigue and speculation, concluded with their tragic disappearance. Despite persistent debate and research, it remains unconfirmed whether the duo succeeded in their audacious quest, transforming their tale into one of mountaineering’s most captivating mysteries.

Over decades, the magnetism of Everest has drawn a tapestry of expeditions, each leaving their unique imprint on the mountain. These successive journeys have established several climbing routes, tracing a web of paths through the treacherous terrain. These routes not only mark the historical progression of Everest exploration but also provide critical insights for future climbers, charting a course through the challenges and dangers of the world’s highest peak. From its initial obscurity to its contemporary renown, Mount Everest continues to evoke a sense of awe and challenge, calling forth generations of climbers to test their mettle against its formidable heights.

The Pursuit of the World’s Highest Summit

Ever since the inaugural documented ascent of Mount Everest in 1953, the mountain has remained an irresistible beacon for mountaineers. However, the high-altitude citadel surrendered its summit sparingly in the early decades, with just about 200 climbers breaching its zenith by 1987. These years were marked by strenuous endeavours by professional climbers and large-scale national expeditions, a trend that endured until the advent of commercial expeditions in the 1990s.

As the turn of the century approached, the frequency of successful ascents began to rise. By March 2012, Everest had been summited 5,656 times, albeit with 223 fatalities, reflecting the inherent risks of such high-altitude pursuits. Despite being less technically demanding compared to certain lower mountains, Everest’s altitude brings it within reach of the jet stream, subjecting climbers to potential winds exceeding 320 km/h (200 mph). While shifts in the jet stream provide periods of relative calm at certain times of the year, the mountain’s environment remains treacherously unpredictable, with blizzards and avalanches posing constant threats.

Nevertheless, the allure of Everest’s summit has proven undeterred. The Himalayan Database, by 2013, had logged 6,871 successful ascents by 4,042 distinct climbers. These statistics bear testimony to the enduring fascination with conquering the world’s highest peak and the indomitable human spirit that spurs on each attempt to reach the roof of the world.

Early Attempts, Forging the Path: Pioneering Expeditions and the Road to Everest’s Conquest

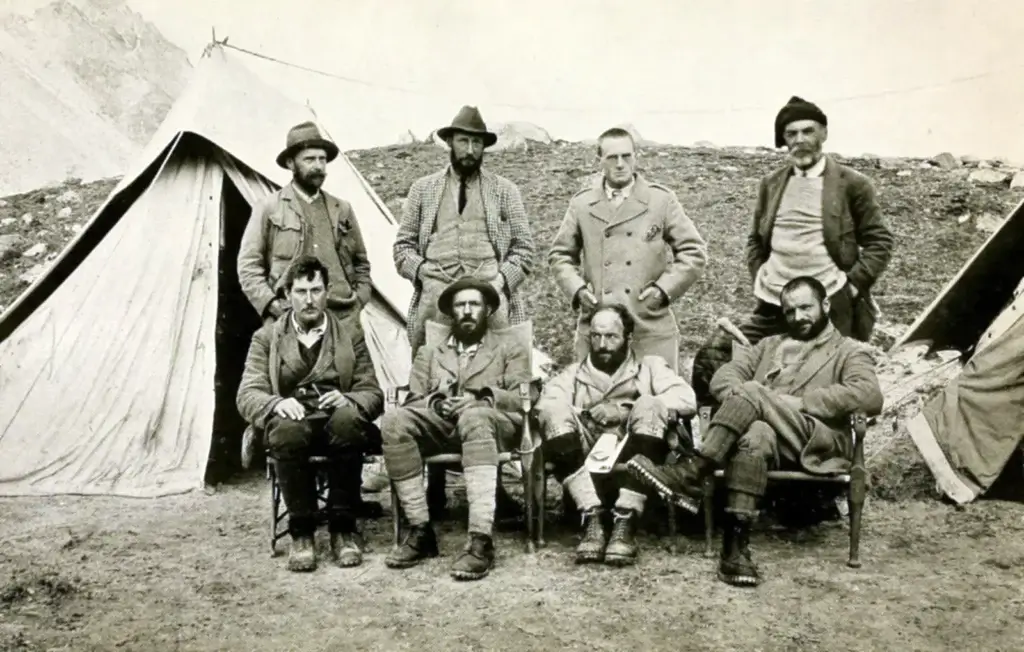

The journey towards conquering Mount Everest commenced in 1885, when Clinton Thomas Dent, the president of the Alpine Club, proposed the idea of ascending the peak in his book “Above the Snow Line”. Yet, it was not until 1921 that the first significant strides were made, courtesy of George Mallory and Guy Bullock during the inaugural British Reconnaissance Expedition. They discovered the northern approach to Everest, ascending to 7,005 metres (22,982 ft) on the North Col. While Mallory envisioned a potential route to the summit, the party lacked the equipment to venture higher.

Determined, the British returned in 1922, equipped with groundbreaking oxygen gear. George Finch, utilizing this equipment, scaled an astonishing 290 metres (951 ft) per hour, reaching a height of 8,320 m (27,300 ft) – the first reported ascent beyond the 8,000 m threshold. Further attempts by Mallory and Col. Felix Norton, however, did not yield success.

Undeterred, another British expedition was launched in 1924. While initial attempts were thwarted by adverse weather, Norton and T. Howard Somervell managed to ascend to 8,550 m (28,050 ft), sans oxygen, under optimal weather conditions. Then, Mallory, joined by Andrew Irvine and equipped with oxygen apparatus, embarked on a fateful ascent on 8 June 1924, from which neither climber returned. Mallory’s body was found in 1999, triggering debates on whether they had successfully summited before their demise, nearly three decades before Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s confirmed conquest of Everest.

In the early 1930s, expeditions continued, marked by endeavours such as the Houston Everest Flight in 1933, funded by British millionairess Lady Houston, which witnessed a formation of two aircraft flying over Everest’s summit. Access from the northern side was closed to Western expeditions in 1950 following China’s control over Tibet, prompting exploratory ventures through Nepal. This led to the formation of what is now the standard southern approach to Everest.

In 1952, Edouard Wyss-Dunant led the significant Swiss Mount Everest expedition through that route. The Swiss team forged a route through the Khumbu icefall, ascending to the South Col at 7,986 m (26,201 ft). Raymond Lambert and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay set a new altitude record by reaching about 8,595 m (28,199 ft) on the southeast ridge. Despite their ultimate retreat due to harsh winter winds, the expedition’s experiences, particularly those of Norgay, would prove instrumental in the successful 1953 British expedition. Thus, the early expeditions, laced with courage, innovation, and resilience, gradually demystified Everest, paving the way for its eventual conquest.

Triumph at the Summit: Hillary and Tenzing’s Historic Conquest

In the annals of mountaineering, the year 1953 marks a landmark moment. This was the year when the 9th British expedition. Led by John Hunt, it returned to Nepal, poised for a fresh attempt on Mount Everest’s summit. Hunt identified two climbing duos for the summit assault. Charles Evans and Tom Bourdillon launched their ambitious climb on 26 May 1953. Despite their valiant efforts, they were forced to retreat a mere 100 m (330 ft) from the summit, grappling with oxygen difficulties. Their pathfinding efforts and strategically placed oxygen caches, however, would prove invaluable for the subsequent pair.

Two days later, Edmund Hillary, a New Zealander, and Tenzing Norgay, a Nepali Sherpa, embarked on their journey towards the summit, following the South Col route. Their painstaking efforts culminated in triumph on the morning of May 29th, 1953, as they stood atop the world’s highest peak. In the spirit of camaraderie that marked the expedition, they celebrated their achievement as a collective victory. Yet, it was later revealed by Tenzing that it was Hillary who had first set foot on the summit. They commemorated their success by taking photographs and leaving behind a few sweets and a small cross in the snow.

The news of their historic ascent reached London on 2 June, coinciding with Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation. Following the euphoria of their achievement, Hunt and Hillary were knighted by the Queen, while Tenzing was awarded the George Medal. In time, Hunt was made a life peer in Britain, and Hillary was included as a founding member of the Order of New Zealand. Both Hillary and Tenzing were honoured in Nepal with statues and the christening of Hillary Peak and Tenzing Peak in their memory, underscoring the lasting legacy of their monumental feat. Their triumph ushered in a new era of high-altitude exploration, etching their names into the saga of Everest, forever synonymous with the audacity of human endeavour.

1950s–1960s – Expanding Horizons: Diverse Climbing Expeditions

Following the historic 1953 ascent, Mount Everest continued to captivate the global mountaineering community throughout the 1950s and 1960s. A flurry of successful summit bids added to the growing legacy of this formidable peak. Ernst Schmied and Juerg Marmet claimed their place in the annals of the Everest conquests on May 23rd, 1956. Their achievement was echoed a year later, on 24 May 1957, by Dölf Reist and Hans-Rudolf von Gunten, further asserting Everest’s allure to climbers worldwide.

The 1960s saw fresh milestones on the Everest timeline. On 25 May 1960, the Chinese trio of Wang Fuzhou, Gonpo, and Qu Yinhua accomplished the first reported ascent from the North Ridge, marking a significant achievement for Asian mountaineering.

Everest’s appeal transcended continents, as demonstrated on 1 May 1963, when Jim Whittaker became the first American to stand atop the world’s highest peak. Accompanied by Nawang Gombu, their ascent carved a new chapter in Everest’s history, extending the roll call of successful climbers to include the United States. Through these ventures, Mount Everest’s reputation as the ultimate mountaineering challenge was reaffirmed, inspiring a generation of climbers and underlining its status as an iconic symbol of human endeavour and resilience.

Explorations and Triumphs: Unforgettable Feats on Mount Everest in the 1970s

The 1970s ushered in a dynamic period of exploration on Mount Everest, marked by a series of remarkable exploits and a fair share of adversity. In 1970, a Japanese expedition led by Saburo Matsukata embarked on an audacious mission to carve out a new route up the formidable southwest face of Everest. The large-scale venture, characterised by a “siege”-style approach, saw over a hundred participants striving to conquer the peak. Despite a decade of meticulous planning, the expedition was unfortunately marred by eight fatalities and failed to reach the summit via the intended routes.

Nonetheless, the Japanese expedition was not without its triumphs. In a breathtaking display of daring, Yuichiro Miura became the first person to ski down Everest from the South Col, descending nearly 1,300 vertical metres (4,200 ft) before suffering severe injuries. Furthermore, another contingent successfully summited via the South Col route. Miura’s adrenaline-charged descent was captured in a film, and he subsequently set records as the oldest person to summit Everest in 2003 and 2013, at ages 70 and 80, respectively.

1975 was a landmark year on Everest, as Junko Tabei, another Japanese mountaineer, etched her name into history as the first woman to conquer the summit. That same year, the British Mount Everest Southwest Face expedition, helmed by Chris Bonington, marked the first successful ascent of Everest’s southwest face from the western cwm.

In 1976, the British and Nepalese Army Expedition, led by Tony Streather, saw Bronco Lane and Brummy Stokes reach the peak following the conventional route.

Yet another feat was achieved in 1978 when Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler ascended Everest without supplemental oxygen, a pioneering achievement that redefined the boundaries of high-altitude mountaineering. The bold ventures and awe-inspiring achievements of the 1970s served to further highlight Mount Everest as a beacon of human endurance and adventurous spirit.

Breaking Barriers: The Historic Winter Ascent of Mount Everest in 1980

As the 1970s drew to a close, the focus of mountaineering shifted to a new challenge: Winter Himalaism. Pioneering this realm was the Polish climber Andrzej Zawada, who led the inaugural winter ascent of Mount Everest in 1980, marking the first successful winter climb of an eight-thousander. The intrepid team, comprising 20 Polish climbers and 4 Sherpas, established their base camp on the Khumbu Glacier in the opening days of January.

Despite establishing Camp III at 7,150 metres above sea level by 15 January, their progress was stymied by hurricane-force winds. A break in the weather after 11 February allowed Leszek Cichy, Walenty Fiut, and Krzysztof Wielicki to set up Camp IV on the South Col at an elevation of 7,906 metres. On 17 February, Cichy and Wielicki embarked on their summit bid. By 2:40 pm, their triumphant voices echoed over the radio at base camp, “We are on the summit! The strong wind blows all the time. It is unimaginably cold.”

This pioneering winter ascent of Mount Everest heralded the advent of a new era in mountaineering, with Winter Himalaism becoming a forte of Polish climbers. Throughout the 1980s, Polish teams achieved an impressive ten first winter ascents of 8000-metre peaks, earning them the moniker of “Ice Warriors”. Their endeavours revolutionised high-altitude climbing, introducing a new dimension of challenge and resilience in the face of Everest’s brutal winter conditions.

Avalanche Tragedy on Mount Everest: The Lho La Incident of 1989

The history of Mount Everest is punctuated with triumphs and tragedies, and one such tragic event unfolded in May 1989. This year bore witness to an international expedition led by the Polish climber Eugeniusz Chrobak, which aimed to conquer the mountain’s formidable western ridge. The expedition comprised ten Polish climbers and nine international participants, although as the climb progressed, only the Polish team members pursued the ultimate goal.

On 24 May, against significant odds, Chrobak and fellow climber Andrzej Marciniak launched their summit bid from Camp V, situated at an altitude of 8,200 m. Overcoming the daunting ridge, they successfully reached the summit. However, their triumph was marred by a tragic turn of events. On 27 May, an avalanche originating from Khumbutse near the Lho La pass claimed the lives of four Polish climbers: Mirosław Gardzielewski, Mirosław Dąsal, Wacław Otręba, and Zygmunt Andrzej Heinrich. Chrobak, who had sustained injuries, succumbed the following day.

Despite the disastrous circumstances, a glimmer of hope emerged when an international rescue operation was organised. The injured Marciniak was saved by a rescue team comprising Artur Hajzer, Gary Ball, Rob Hall, and others. Notable personalities like Reinhold Messner, Elizabeth Hawley, Carlos Carsolio, and the US consul also contributed to the organisation of the rescue operation. The Lho La tragedy stands as a sobering reminder of the inherent risks of high-altitude mountaineering, underscoring the extreme challenges that Everest poses even to the most experienced climbers.

The 1996 Everest Tragedy: Peril and Resilience on the Roof of the World

The allure of Mount Everest has often been juxtaposed with its inherent dangers, with the tragedy that struck in May 1996 standing out as one of the mountain’s deadliest episodes. On 10 and 11 May, a sudden blizzard trapped several guided expeditions high on Everest during their summit attempt. Eight climbers tragically lost their lives, and the season’s overall death toll reached 15, the highest for any single weather event and single season until the catastrophic avalanche in 2014.

This disaster brought the commercialisation of climbing and the safety protocols of guided expeditions on Everest into sharp focus. Jon Krakauer, a journalist who was part of one of the guided parties, penned the bestselling book “Into Thin Air“, providing a first-hand account of the event. Krakauer’s critical portrayal of guide Anatoli Boukreev sparked controversy and spurred Boukreev to co-author “The Climb” as a rebuttal, leading to a significant debate within the climbing community. For his rescue efforts, Boukreev was posthumously awarded The American Alpine Club’s David Sowles Award.

Researchers Kent Moore and John L. Semple analysed the weather conditions on 11 May, suggesting that oxygen levels fell by an estimated 14% due to the storm. Among the survivors was Beck Weathers, who incredibly managed to return to Camp 4 despite severe frostbite and snow blindness. After a night on the mountain, he was left in a tent, as his condition was considered terminal. Yet, in a testament to human resilience, Weathers survived and was eventually evacuated by a Nepali Army helicopter, an extraordinary feat considering the high altitude of Camp 4.

The North Ridge of Everest was also heavily impacted by the storm, with several climbers losing their lives. Detailed accounts of the event emerged in various formats, from Matt Dickinson’s “The Other Side of Everest” to Mark Pfetzer’s “Within Reach: My Everest Story”. The harrowing ordeal was further brought to life in the 2015 feature film “Everest” directed by Baltasar Kormákur, underscoring the perilous nature of Everest expeditions and the indomitable human spirit in the face of life-threatening adversity.

Ethics and Survival: The Controversy of David Sharp and the Miraculous Rescue of Lincoln Hall on Mount Everest, 2006

The 2006 mountaineering season on Mount Everest stands out as a year of stark contrasts, marked by both deep tragedies and improbable survivals. A total of twelve climbers lost their lives that year, one of the highest death tolls on record. One death, in particular, cast a long shadow over the season and ignited an international debate about the ethics of high-altitude climbing, sparking discussions that would continue for years. However, amid these unfortunate fatalities, an inspiring tale of survival emerged. Lincoln Hall, an Australian climber, was left for dead by his own team only to be discovered alive the following day. His remarkable rescue off the mountain served as a poignant reminder of human resilience in the face of Everest’s formidable challenges.

Controversial Solo Ascent: The Tragic Death of David Sharp and the Ethical Debate on Mount Everest, 2006

The 2006 mountaineering season on Mount Everest was marred by a tragic event that spurred an international debate on climbing ethics. The heart of the controversy centred around the death of David Sharp, a British climber who attempted the daring feat solo, resulting in fatal consequences.

The Solo Summit Attempt

Sharp embarked on his expedition with fewer oxygen bottles than considered typical for a summit attempt, declining the assistance of a Sherpa or guide. Opting for the services of a low-budget Nepali guide firm, Sharp received support only until Base Camp, beyond which he was part of a “loose group,” ensuring a significant degree of independence. The manager of Sharp’s guide support noted his lack of sufficient oxygen for the summit attempt and the absence of a Sherpa guide, factors contributing to the tragic outcome. On 15 May 2006, suffering from hypoxia, Sharp was believed to be in trouble, roughly 300 meters from the summit on the North Side route.

A Climbing Community in Conflict

Double-amputee climber Mark Inglis and his climbing party, along with numerous others, reported passing by Sharp, who was taking shelter under a rock overhang. This sparked widespread debate, as Sharp might have been overlooked, with climbers presuming he was the previously deceased climber known as “Green Boots“. Inglis’s comments were later revised, attributing initial inaccuracies to physical and mental exhaustion, along with the pain from severe frostbite, which later led to the amputation of five of his fingertips.

The controversy was exacerbated by reports of an attempted rescue by Dawa from Arun Treks, who had given Sharp oxygen and tried to assist him for approximately an hour. Despite these efforts, Sharp’s condition deteriorated to the point where he could not stand alone or even lean on Dawa’s shoulders, leading Dawa to leave him behind.

Media Spotlight and Aftermath

The tragedy unfolded under the spotlight of international media and elicited strong reactions from the mountaineering community. The incident sparked an introspective dialogue about the duty of climbers to aid fellow mountaineers in distress.

The story was widely covered by the Discovery Channel in the program “Everest: Beyond the Limit,” which featured a crucial decision affecting Sharp’s fate. Lebanese climber Maxim Chaya, upon discovering a frostbitten and unconscious climber in distress, communicated the situation to his base camp manager, Russell Brice. Unable to identify the unresponsive climber as Sharp, who was attempting the climb solo without any support, Chaya was advised that there was no chance of him helping Sharp alone.

As Sharp’s condition worsened throughout the day, his rescue prospects diminished. His frostbitten legs and feet curled, rendering him incapable of walking, and the descending climbers passing by him were low on oxygen and lacked the strength to provide assistance. Eventually, time ran out for any potential Sherpa rescue.

The memory of David Sharp endures on Everest. His body, along with that of the unidentified “Green Boots“, once shared a space in a small rock cave serving as an improvised tomb. The tragedy of David Sharp’s death remains a stark reminder of the ruthless environment of Mount Everest and the ethical challenges it presents to those who dare to scale its heights.

Miraculous Rescue: Lincoln Hall’s Astonishing Survival on Mount Everest, 2006

Just as the climbing world was grappling with the ethics controversy surrounding the death of David Sharp in May 2006, a remarkable event transpired on Mount Everest that served as a beacon of hope. Australian climber Lincoln Hall, who had been left for dead on the mountainside the day before, was found alive.

An Unexpected Encounter

On the fateful morning of 26 May 2006, a team of four climbers – Dan Mazur, Andrew Brash, Myles Osborne, and Jangbu Sherpa – encountered Hall at an altitude of 28,200 feet with no gloves, hat, oxygen bottles, or sleeping bag. Mazur, the team leader, expressed his disbelief upon finding Hall just sitting there at the break of dawn. Sacrificing their own summit attempt, they elected to stay with Hall, marking the start of an incredible rescue mission.

Hall’s initial response to his rescuers was one of quiet acceptance. He greeted his fellow climbers simply with, “I imagine you are surprised to see me here.” His calm demeanour belied the severity of his situation. His team had assumed he had succumbed to cerebral oedema, a potentially fatal altitude sickness that causes brain swelling. With no rocks in the vicinity to cover him as instructed, he was left abandoned, and the erroneous information about his demise was passed on to his family.

The Rescue and Aftermath

The group of four climbers, in conjunction with a rescue team of 11 Sherpas dispatched from below, carefully descended with Hall, ensuring his survival. Against all odds, Hall made a full recovery, living to share his near-death experience on Mount Everest with audiences worldwide.

His miraculous survival story served as a stark contrast to the tragedy that unfolded during the same season on Everest, shedding light on the extreme challenges and ethical dilemmas encountered in high-altitude mountaineering. Hall continued to talk about his experience and the importance of survival instincts and teamwork in the unforgiving conditions of Mount Everest until his death in 2012, at the age of 56, from unrelated medical issues. His story is a testament to the power of human resilience and the indomitable spirit of survival.

2007: Everest’s Record Ascents, Rescue Heroism, and Challenges of Overcrowding

The 2007 mountaineering season on Mount Everest was marked by notable ascents and successful rescues, alongside an ongoing examination of the risks climbers faced. A pivotal moment came on 21 May when Meagan McGrath, a Canadian climber, initiated the successful high-altitude rescue of Nepali climber Usha Bista. McGrath’s quick response and humanitarian act later earned her the 2011 Sir Edmund Hillary Foundation of Canada Humanitarian Award.

The popularity of Everest expeditions showed no signs of waning in 2007, with the mountain experiencing a record number of 633 ascents, accomplished by 350 climbers and 253 Sherpas. This marked a tremendous growth in Everest climbing, with 77 per cent of all ascents occurring since the turn of the millennium.

The 2007 season also underscored the potential challenges of overcrowding on Everest. Comparing the 1996 disaster, where a then-unusual number of 33 to 36 climbers attempting to summit on the same day contributed to fatal delays, the number of climbers has increased dramatically. For instance, on 23 May 2010, the summit was reached by a staggering 169 climbers, more than the total number of summits from 1953 through 1983.

However, this popularity brought an inevitable toll. Up to the end of 2010, there had been 219 fatalities recorded on Mount Everest, a rate of 4.3 deaths for every 100 summits. Despite a decrease in fatality rates since the year 2000, the sheer increase in the total number of climbers resulted in 54 fatalities from 2000 to 2010.

The route to the summit also proved to be a point of interest during this period. Two main routes are generally used, their popularity varying from year to year. The more challenging but less costly northeast route attracted more than half of all climbers from 2005 to 2007. However, closures by the Chinese government in 2008 and 2009 for political reasons saw a decrease in its usage. By 2010, the majority of climbers, two-thirds in fact, opted to ascend via the southern route.

The 2010s on Everest: Records, Setbacks, and the Unyielding Allure

The 2010s on Mount Everest witnessed a whirlwind of contrasts, from new records set to unprecedented challenges. While this decade for Everest brought an influx of climbers eager to conquer the peak, it was also marred by back-to-back disasters that resulted in record fatalities in 2013 and 2014.

For the first time in decades, 2015 saw a barren year without any successful ascents. This unique occurrence stood as a stark reminder of the unforgiving nature of the world’s highest peak and the capriciousness of the conditions that could stall even the most ambitious expeditions.

However, despite the setbacks, the lure of Everest remained undiminished. In a testament to the enduring allure of the mountain, the later part of the decade saw an influx of climbers achieving the coveted summit. The record set in 2013 for the number of successful ascents, standing at around 667, was toppled five years later when approximately 800 climbers managed to reach the peak in 2018.

The allure of Everest remained strong, and its attraction was only heightened in the following year. The record set in 2018 was promptly broken the very next year, with more than 890 climbers reaching the summit in 2019. These figures underscored the ongoing fascination with Mount Everest, demonstrating the determination of adventurers to test their limits against the awe-inspiring challenge of the world’s highest peak.

The 2014 Season: Tragedy, Triumphs, and Unyielding Spirit

A tragic avalanche and exceptional ascents marked the 2014 season on Mount Everest. An avalanche that struck just below Base Camp 2 in the early hours of 18 April was one of the deadliest incidents in the mountain’s history. The avalanche hit at around 01:00 UTC (06:30 local time) at an elevation of approximately 5,900 metres (19,400 ft). It claimed the lives of 16 Nepali guides and inflicted injuries on an additional nine individuals, casting a sombre shadow over the climbing season.

In the face of such adversity, a few climbers nonetheless made their mark. The season saw the youngest female climber, a 13-year-old girl named Malavath Purna, conquer the summit. Her accomplishment served as an inspiring testament to determination and youthful audacity.

An inventive approach to tackling the mountain was seen when one team used a helicopter to fly from the South Base Camp to Camp 2, bypassing the treacherous Khumbu Icefall. A member of this team, Jing Wang, who was compelled to use the south side after the Chinese authorities denied them a permit to climb, generously donated US$30,000 to a local hospital. In recognition of her significant contribution, she was honoured as the Nepali “International Mountaineer of the Year”.

Despite the season’s grim beginning, more than 100 climbers still reached the summit from China’s Tibet region, and six ascents were recorded from Nepal. The successful summiters included 72-year-old Bill Burke, the young Indian climber Malavath Purna, and Jing Wang from China. Ming Kipa Sherpa, another young female climber, who had previously reached the summit with her elder sister Lhakpa Sherpa in 2003, also returned. Lhakpa Sherpa had by then distinguished herself by summiting Mount Everest more times than any other woman at that time.

A Season of Devastation: The 2015 Earthquake and Avalanche on Everest

The 2015 climbing season on Mount Everest was set to be a record-breaker, with permits for ascents issued in their hundreds in both Nepal and Tibet. Yet, Mother Nature had other plans. On 25 April 2015, a powerful earthquake measuring 7.8 Mw struck, triggering a deadly avalanche that engulfed Everest Base Camp. This catastrophic event led to the death of 18 climbers; their bodies were later recovered by an Indian Army mountaineering team. The avalanche, initiated on Pumori, travelled through the Khumbu Icefall on Everest’s southwest side and devastated the South Base Camp.

The catastrophe caused the Everest climbing season to come to an abrupt halt, marking 2015 as the first year since 1974 with no successful spring summits. All climbing teams were compelled to withdraw due to the substantial risk of aftershocks, which the United States Geological Survey estimated at over 50 per cent. This prediction proved accurate when the region was rocked once again by a 7.3 magnitude quake just weeks later, accompanied by numerous significant aftershocks.

The aftermath of the earthquakes was chaotic. Hundreds of climbers found themselves stranded above the Khumbu Icefall, and as supplies dwindled, they had to be evacuated by helicopter. The quake had altered the route through the icefall, making it virtually impassable. Complicating matters further, adverse weather conditions often hampered the helicopter evacuation efforts.

However, the Everest tragedy was minor compared to the devastation wrought across Nepal, where nearly 9,000 people perished and approximately 22,000 were injured. By 28 April, at least 25 people had died, with 117 injured, in Tibet. The Tibet Mountaineering Association, by 29 April 2015, closed Everest and other peaks to climbing, leaving 25 teams and about 300 people stranded on the mountain’s north side. On the south side, helicopters rescued 180 people marooned at Camps 1 and 2.

A Season of Triumph and Tragedy: The 2019 Climbing Season on Mount Everest

The 2019 pre-monsoon climbing window on Mount Everest was a season of notable triumphs and tragedies. The untimely deaths of several climbers marked this period, and media worldwide published startling images of hundreds of mountaineers caught in queues to reach the summit. Reports of climbers stepping over deceased climbers shocked audiences globally.

Before the main Everest climbing season, various winter expeditions to other peaks in the Himalayas created a buzz, including those to K2, Nanga Parbat, and Meru. Among these, renowned climber Cory Richards announced plans to establish a new route to Everest’s summit in 2019. Another intriguing expedition aimed to remeasure the height of Everest, particularly in the aftermath of the 2015 earthquakes.

By early April, teams from around the globe started arriving for the 2019 spring climbing season. These included a scientific expedition to study pollution, as well as the impact of factors like snow and vegetation on the availability of food and water in the region. On the Nepali side alone, about 40 teams, comprised of approximately 400 climbers and hundreds of guides, attempted to summit. Nepal issued 381 climbing permits that year, while authorities in Chinese Tibet granted several hundred additional permits for the northern routes.

The season saw Nepali mountaineering guide, Kami Rita, making international headlines by summiting Mount Everest twice within a week, marking his 23rd and 24th ascents. His first Everest summit took place in 1994, and he has also climbed other formidable peaks such as K2 and Lhotse.

By 23 May 2019, about seven people had tragically lost their lives, possibly due to the congestion leading to delays high on the mountain and shorter weather windows. By 26 May 2019, the death toll for the spring climbing season had risen to 10. The fatalities increased to 11 by 28 May, and a 12th climber went missing and was presumed dead. Despite these tragedies, the 2019 spring climbing season set a new record with approximately 891 climbers reaching the summit.

The 2019 climbing season, despite various permit restrictions from China and a required doctor’s approval for climbing permits from Nepal, will be remembered for its high death toll, attributed to the natural dangers of climbing and medical complications exacerbated by the extreme altitude of Everest.

Conquering Everest: Challenges and Triumphs Across Seasons and Altitudes

Permits and Restrictions: Navigating the Regulations to Conquer Mount Everest

Climbing Mount Everest, the world’s highest peak requires acquiring the necessary permits issued by the authorities of Nepal and China. In 2014, Nepal issued 334 climbing permits, which were extended until 2019 due to the closure of the mountain. In 2015, Nepal issued 357 permits, but yet again, the mountain was closed due to an avalanche and earthquake. These permits were thus extended for use until 2017.

The consequence of attempting to climb Everest without the required permit can be severe, as evidenced in 2017 when a climber bypassed the Khumbu Icefall without the $11,000 permit. He was apprehended and faced multiple penalties, including a fine of $22,000 and a potential jail term of up to four years. While he was ultimately allowed to return home, he was banned from mountaineering in Nepal for a decade.

The northern side of Everest, located in the Chinese region of Tibet, also mandates the need for permits to summit the peak. Notably, no permits were issued in 2008 due to the Olympic torch relay’s ascent to the summit of Mount Everest.

The year 2020 saw the unprecedented cancellation of all climbing permits for Mount Everest by both China and Nepal due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the restrictions, a group of Chinese mountaineers began an expedition from the Chinese side in April 2020. The mountain remained closed to foreign climbers on the Chinese side. In May 2021, Chinese authorities introduced a separation line on the summit to prevent the potential spread of coronavirus from climbers ascending from Nepal’s side of the mountain.

Two Routes, One Dream: Scaling Mount Everest’s Southeast and North Ridges

The formidable Mount Everest offers climbers a selection of routes towards its summit, with two primary paths standing out – the southeast ridge from Nepal and the north ridge from Tibet. Numerous other paths exist but are less frequently embarked upon. The southeast ridge, considered technically easier, is the more commonly trodden path. This was the route taken by the pioneering mountaineers Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay in 1953. The choice of this route was more a product of political circumstances than design, as the Chinese border was inaccessible to the Western world in the 1950s after the People’s Republic of China invaded Tibet.

The window for most climbing attempts comes in May, just before the onset of the summer monsoon season. During this period, the shifting jet stream mitigates the high wind speeds at the mountain’s summit. While attempts are made in September and October, post-monsoon, the increased snowfall and unstable weather conditions, consequences of the tail end of the monsoons, make the ascent exceedingly challenging.

The Journey Up Everest’s Southeast Ridge: From Base Camp to the Summit

Embarking on a journey via the southeast ridge of Mount Everest commences with a trek to Base Camp, situated at an altitude of 5,380 m (17,700 ft) in Nepal. Initial steps see expeditions fly into Lukla (2,860 m) from Kathmandu before passing through Namche Bazaar. From here, a six to eight-day hike leads climbers to Base Camp, a journey purposefully designed for adequate altitude acclimatisation to help combat altitude sickness. Supplies and climbing equipment are typically transported to the Base Camp on the Khumbu Glacier by yaks, dzopkyos (yak-cow hybrids), and human porters.

Following arrival, climbers spend around two weeks at Base Camp to acclimatise to the high altitude. During this time, Sherpas and some expedition climbers install ropes and ladders across the perilous Khumbu Icefall, one of the most hazardous sections of the route, fraught with crevasses, shifting ice blocks, and towering seracs. To minimise risk, climbers usually initiate their ascent before dawn when freezing temperatures help secure the ice blocks.

Beyond the icefall lies Camp I, perched at an elevation of 6,065 metres (19,900 ft). From this point, climbers navigate up the Western Cwm to the foot of the Lhotse face, where Advanced Base Camp (”ABC”) or Camp II is set up at 6,500 m (21,300 ft). The Western Cwm is a gently rising glacial valley notorious for its immense lateral crevasses that hinder direct access to the upper reaches. As such, climbers are compelled to cross to the far right, towards the base of Nuptse, and pass through a narrow passage known as the “Nuptse corner”.

From ABC, climbers, with the assistance of fixed ropes, ascend the Lhotse face, reaching Camp III, a small ledge at 7,470 m (24,500 ft). It’s a further 500 metres to Camp IV, situated on the South Col at 7,920 m (26,000 ft). Between Camp III and Camp IV, climbers encounter two distinct challenges: the Geneva Spur and the Yellow Band.

Upon reaching the South Col, climbers enter the infamous “death zone”. This altitude is so extreme that climbers can only endure two to three days at most. Any summit attempts must occur within this window, with clear, low-wind weather being vital. If these conditions do not present themselves, climbers are forced to descend, in many cases, as far back as Base Camp.

The summit push typically begins at midnight from Camp IV, aiming to reach the summit within 10 to 12 hours. Climbers encounter a series of formidable obstacles, including the notorious Hillary Step at 8,790 m (28,840 ft). Once above the step, it is a relatively easy climb to the top, albeit with extreme exposure along the ridge, especially while traversing large cornices of snow.

The Hillary Step has become a major bottleneck in recent years due to increasing numbers of climbers, causing delays and subsequent problems with efficient ascents and descents. Beyond the Hillary Step, climbers face a loose, rocky section fraught with tangled fixed ropes. Once surmounted, climbers typically spend less than half an hour at the summit due to rapidly changing afternoon weather, dwindling supplemental oxygen supplies, and the need to reach Camp IV before nightfall.

Scaling the North Ridge: Challenges and Triumphs on Everest’s Tibetan Route

The North Ridge route, commencing from the northern side of Everest in Tibet, starts with an expedition to the Rongbuk Glacier. The base camp is established on a gravel plain just beneath the glacier at an altitude of 5,180 m (16,990 ft). The journey to Camp II involves an ascent of the medial moraine of the east Rongbuk Glacier, arriving at the base of Changtse at approximately 6,100 m (20,000 ft).

Advanced Base Camp (ABC), or Camp III, is located beneath the North Col at 6,500 m (21,300 ft). Climbers scale the glacier to the base of the col, where fixed ropes aid the ascent to the North Col, or Camp IV, at 7,010 m (23,000 ft). From the North Col, the rocky north ridge is ascended to establish Camp V at around 7,775 m (25,500 ft). The route then cuts across the North Face diagonally, leading to the base of the Yellow Band and the location of Camp VI at 8,230 m (27,000 ft). From here, climbers gear up for their final push towards the summit.

One of the major challenges on this route is a treacherous traverse from the base of the First Step, ascending from 8,501 to 8,534 m (27,890 to 28,000 ft), followed by the crucial Second Step, ascending from 8,577 to 8,626 m (28,140 to 28,300 ft). The Second Step is notorious for a climbing aid known as the “Chinese ladder,” a metal structure installed semi-permanently in 1975 by a Chinese climbing party. The ladder has since been a fixture of the climb, used by nearly all climbers who embark on this route.

Beyond the Second Step lies the comparatively minor Third Step, from 8,690 to 8,800 m (28,510 to 28,870 ft). Once surmounted, climbers face the summit pyramid, a 50-degree snow slope, which leads to the final summit ridge and, ultimately, the peak of Mount Everest.

Summit and Beyond: Exploring the Terrain of Mount Everest

The pinnacle of Mount Everest, often compared to the dimensions of a dining room table, is capped with layers of snow over ice over rock. The thickness of the snow varies annually. The rock at the summit is a low-grade metamorphic rock formed of Ordovician limestone.

As one descends from the summit, an area known as the “Rainbow Valley” unfolds. It derives its name from the brightly coloured winter gear adorning the numerous bodies of fallen climbers that lay strewn across the valley. Further down, at about 8,000 m (26,000 ft), lies the ominously named “death zone”. This area is known for its high risk and low oxygen levels due to low atmospheric pressure.

From here, the slopes of Mount Everest descend towards the three principal faces of the mountain: the North Face, the South-West Face, and the East or Kangshung Face. Each of these faces presents a unique and challenging terrain for climbers to navigate in their quest to conquer the world’s highest peak.

The Perils of the Death Zone: Surviving at Extreme Altitudes

The upper reaches of Mount Everest, altitudes beyond 8,000 metres (26,000 ft), known as the death zone, pose significant survival challenges to climbers. Temperatures in this zone can drop significantly, causing severe frostbite on any exposed body part. Certain areas in the death zone are frozen solid, making slipping and falling a tangible risk. Climbers also need to contend with high winds that could become potential hazards.

One of the most critical threats at these elevations is the low atmospheric pressure. At Everest’s summit, the atmospheric pressure is approximately a third of sea level pressure, resulting in only about a third as much available oxygen to breathe. This low oxygen availability makes the journey from South Col to the summit, a distance of 1.72 kilometres (1.07 mi), a gruelling endeavour that can take up to 12 hours. Even this achievement requires prolonged altitude acclimatisation, typically taking 40–60 days for an average expedition. Without acclimatisation, a person from sea level would likely lose consciousness within 2 to 3 minutes at these elevations.

The Caudwell Xtreme Everest medical study in May 2007 evaluated blood oxygen levels at extreme altitudes. Test results showed a decrease in blood oxygen saturation levels even at base camp. At sea level, oxygen saturation is around 98 to 99 per cent, which drops to 85 to 87 per cent at base camp. Tests conducted at the summit indicated dangerously low oxygen levels in the blood, leading to a significantly increased breathing rate, often 80–90 breaths per minute compared to the normal 20–30. This state can lead to exhaustion just from the effort of breathing.

Multiple factors such as oxygen deficiency, exhaustion, extreme cold, and climbing hazards contribute to the death toll on Everest. An injured person who cannot walk faces grave danger, as helicopter rescue is generally unfeasible, and physically carrying the person down is high risk. Bodies of climbers who die during their ascent are usually left on the mountain, and as of 2015, over 200 bodies remain.

A 2008 study pointed out that most deaths occur in the death zone, predominantly during the descent. The risk of falling in this zone is significant but avalanches present a more common danger at lower altitudes. However, even with these risks, by certain measures, Everest is safer than peaks such as Kangchenjunga, K2, Annapurna, Nanga Parbat, and the Eiger, with the overall lethality of a mountain influenced by factors like its popularity, the skill level of climbers, and the difficulty of the climb.

Another potential health risk in the death zone is retinal haemorrhages, which can impair vision and lead to blindness. Up to a quarter of Everest, climbers may experience this condition, which generally heals within weeks upon returning to lower altitudes. However, in one case in 2010, a climber went blind in the death zone and subsequently died.

In this unforgiving environment, rescuing an incapacitated individual can be an insurmountable challenge. One innovative solution was attempted by two Nepali men in 2011, who were forced to paraglide off the summit due to depleted oxygen and supplies. Their high-risk strategy succeeded, and they descended to Namche Bazaar in just 42 minutes, circumventing the perilous climb down.

Oxygen and Everest: The Lifeline and Controversy

The endeavour to conquer Everest is an immense undertaking, and for most climbers, oxygen masks and tanks become indispensable equipment above 8,000 m (26,000 ft). The human capacity for clear thought diminishes with decreasing oxygen levels, a condition that poses serious risks given the harsh weather, biting cold, and steep slopes that often necessitate swift, precise decision-making. While about five per cent of climbers have ascended Everest without supplemental oxygen, the death rate doubles for these audacious individuals.

The use of bottled oxygen in ascending Mount Everest has been controversial since its first application during the 1922 British Mount Everest Expedition. George Finch and Geoffrey Bruce, despite achieving a remarkable ascent rate by employing oxygen, faced criticism from the wider alpine community that deemed the practice unsportsmanlike. Nevertheless, George Mallory, an initial critic of oxygen use, resorted to it during his final attempt in 1953, while Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary also used open-circuit bottled oxygen sets during their first successful summit that same year.

The tradition of using supplemental oxygen was first broken by Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler in 1978, followed by Messner’s solo summit without oxygen or any climbing partners in 1980. This shift in the climbing community opened up the debate about how Everest should be climbed, with many purists insisting on an oxygen-free ascent.

The catastrophic events of the 1996 Everest disaster amplified this debate. Jon Krakauer, in his book “Into Thin Air“, argued that bottled oxygen allowed marginally qualified climbers to attempt the summit, leading to hazardous situations and more fatalities. He proposed banning its use, except in emergencies, to reduce the increasing pollution on Everest’s slopes and the number of potentially unqualified climbers on the mountain.

The disaster also highlighted the guide’s role concerning bottled oxygen. Krakauer criticised guide Anatoli Boukreev’s decision to forego bottled oxygen, though Boukreev’s supporters counterargued that supplemental oxygen gives a false sense of security.

A significant concern tied to low oxygen levels is the resultant cognitive impairment, described as a “delayed and lethargic thought process,” or bradypsychia, which can persist even after descending to lower altitudes. In severe instances, climbers can experience hallucinations, and some studies have found altered brain structure in high-altitude climbers. Research continues on the impacts of high altitude on the brain and the potential for permanent damage.

Autumn Ascents: Conquering Everest’s Perilous Season

While spring is the prime season for Everest expeditions, the mountain has also been conquered in autumn, or the “post-monsoon season.” The autumnal period, however, is regarded as more perilous due to the typically heavy, new snowfall that can lead to instability. Yet, paradoxically, this increased snow also attracts certain winter sports enthusiasts, with skiing and snowboarding attempts becoming increasingly popular.

There are significant historical autumn ascents to note. In 2010, Eric Larsen and his team of five Nepali guides made it to the summit, marking the first autumnal ascent in a decade. Going further back, two Japanese climbers reached their peak in October 1973. Chris Chandler and Bob Cormack of the American Bicentennial Everest Expedition also successfully summited in October 1976, becoming the first Americans to achieve an autumn ascent, as reported by the Los Angeles Times.

In the 1980s, autumn climbing was even more popular than spring expeditions. However, the season is not without its tragedies: U.S. astronaut Karl Gordon Henize, for example, died on an autumn expedition in October 1993 while conducting a radiation experiment, a significant risk factor as background radiation intensifies with altitude.

Winter climbs, while feasible, are rarely undertaken due to the harsh conditions climbers must endure. With 170 mph (270 km/h) winds, average temperatures around −33 °F (−36 °C), and reduced daylight, winter presents the most formidable of Everest’s seasonal challenges.

Everest Commercialization: Costs, Controversies, and Challenges

The Commercialization of Everest: Guided Tours and Financial Realities

The landscape of Everest climbing experienced a transformation in 1985, marking the start of the commercialisation era of Everest. This shift was catalyzed by an expedition led by David Breashears, where Richard Bass, a wealthy 55-year-old businessman with a mere four years of climbing experience, successfully reached the summit. By the early 1990s, numerous companies were capitalising on this commercial trend, offering guided tours to Everest’s peak.

One notable guide was Rob Hall, who, despite his tragic demise in the 1996 disaster, had an illustrious record of guiding 39 clients to the Everest summit. Over the years, the cost of these guided services has escalated, with most ranging from US$35,000 to a staggering US$200,000 by 2016. The price climbs even steeper for those desiring the guidance of a “celebrity guide”—a renowned mountaineer with extensive climbing experience and possibly multiple Everest ascents—exceeding £100,000 in 2015.

However, potential climbers are advised to proceed with caution. Services offered can fluctuate wildly, and the nature of conducting business in Nepal, one of the world’s poorest and least developed countries, necessitates a “buyer beware” mindset. Despite the country grappling with high unemployment, tourism, contributing 7.9 per cent of the GDP in 2019, offers a lifeline for many. Everest holds a unique position in this landscape; porters can earn nearly double the nation’s average wage, providing a crucial income source in a region with few alternatives.

Cost Considerations: The Financial Realities of Climbing Everest

The pursuit of climbing Everest comes with a variety of financial considerations. While it is feasible to ascend with minimal additional expenses, many opt for the services of travel agencies offering logistical support, and even “budget” options exist that provide a stripped-down version of these services. For as little as US$7,000, as of 2007, climbers can avail of a limited support service that includes some meals at base camp and administrative necessities such as obtaining a permit. However, this budget approach is often seen as more difficult and perilous, as illustrated by the case of David Sharp.

The cost of equipment necessary for a successful summit attempt can exceed US$8,000, and most climbers opt to use bottled oxygen, adding approximately US$3,000 to their expenses. Entry permits to the Everest region via Nepal can range from US$10,000 to US$30,000 per person, contingent on the team size. With both base camps situated roughly 100 kilometres (60 miles) from Kathmandu and 300 kilometres (190 miles) from Lhasa, transportation of equipment from these major airport hubs to base camp can add a further expense of up to US$2,000.

Many climbers opt to hire “full service” guide companies, which offer comprehensive packages covering a wide array of services. These can include permit acquisition, transportation to and from base camp, provision of food and tents, setting of fixed ropes, on-mountain medical assistance, the guidance of an experienced mountaineer, and even the services of personal porters to carry backpacks and prepare meals. The cost for such services can range from US$40,000 to $80,000 per person. Engaging such services often allows climbers to maintain their backpack weight below 10 kilograms (22 lbs) as Sherpas transport most equipment. Some even opt to hire a Sherpa to carry their backpacks. This stands in stark contrast to the experiences on less commercialised peaks, such as Denali, where climbers are frequently expected to carry backpacks exceeding 30 kilograms (66 lbs) and occasionally tow a sled loaded with 35 kilograms (77 lbs) of equipment and food.

Controversies of Commercialization: Challenging the Spirit of Mountaineering

The commercialisation of Mount Everest has sparked ongoing controversy in the climbing community. Critics argue that the mountain’s spirit of adventure is being eroded as inexperienced climbers, equipped with ample funds but little knowledge, ascend its slopes. Jamling Tenzing Norgay, son of famed Everest climber Tenzing Norgay, expressed concern over the safety implications and loss of the mountaineering spirit. He criticized the increasing trend of inexperienced climbers relying on paid services to reach the summit, a practice he deems selfish due to the potential endangerment of others’ lives.

A testament to this criticism was the 2012 incident involving Shriya Shah-Klorfine, who paid a new guiding company at least US$40,000 for her summit attempt. Shah-Klorfine had such minimal climbing experience that she had to be taught how to don crampons during her climb. Tragically, she died during her descent after a gruelling 27-hour summit attempt, highlighting the potentially fatal consequences of such ventures.

Reinhold Messner, a renowned mountaineer, echoed this sentiment in 2004, lamenting the transformation of high-altitude alpinism into a form of tourism and spectacle. He argued that real mountaineering necessitated an understanding of the inherent risks and dangers. Messner critiqued the false sense of security provided by commercial expeditions, which promise clients safety with prepared routes, extra oxygen, and full camp services. He expressed concern that these assurances led climbers to disregard the risks, consequently endangering lives and undermining the true essence of mountaineering.

Regulations: Balancing Safety and Accessibility

In the context of the commercialisation and increasing accessibility of Mount Everest, the Nepalese government contemplated new regulations by 2015 to enforce climbers’ experience before attempting the summit. The twin goals of this proposition were to enhance the safety of climbers on Everest’s treacherous slopes and boost the economic revenue of climbing tourism.

Despite this proposition, lower-budget firms often capitalise on taking less experienced climbers at least partway up the mountain. In contrast to Western firms that persuade climbers deemed unfit to retreat, these companies give clients the autonomy to decide, sometimes resulting in inexperienced climbers venturing dangerously high.

Nevertheless, some celebrated mountaineers hold nuanced views of the changing Everest landscape. Edmund Hillary, a renowned Everest climber, admitted his dissatisfaction with paying substantial fees for guided ascents, as he felt it stripped away the essence of mountaineering. Yet he also acknowledged the significant improvements brought to the Everest region by Western influence. His endeavours, in collaboration with Sherpa communities, have led to enhanced local living conditions, including establishing schools, hospitals, medical clinics, bridges, and freshwater pipelines.

Emphasising the imperative of prior high-altitude experience, Richard Bass, an early guided summiter, highlighted the gross underestimation of Everest’s challenges. He cautioned against the misconception of equating the experience of climbing lower peaks like Denali or Aconcagua with that of Everest. According to Bass, the effect of altitude on the human body increases exponentially with height, making the journey to Everest’s summit profoundly more challenging than other mountains.

Extreme Everest: A Playground for High-Altitude Sports

Mount Everest, the pinnacle of the Earth, has served as a captivating stage not only for mountaineering but also for a broad spectrum of adrenaline-charged extreme sports. Enticed by its formidable heights and challenging conditions, daredevils from across the globe have turned to Everest to push the boundaries of snowboarding, skiing, paragliding, and even the audacious act of BASE jumping.

Downhill Daredevils: Skiing and Snowboarding

Pushing the boundaries of extreme sports, adventurers have taken to Mount Everest not just to climb, but to ski and snowboard down its imposing slopes. The first to perform such an audacious feat was Yuichiro Miura in the 1970s. Despite suffering serious injuries, Miura skied nearly 1,300 vertical metres from the South Col, marking the initiation of skiing expeditions on Everest.

The 21st century brought more winter sports enthusiasts to Everest’s challenging terrains. Stefan Gatt and Marco Siffredi carved their snowboarding paths down Everest in 2001, marking another milestone in high-altitude sports. Several daring individuals have attempted skiing descents, including Davo Karničar of Slovenia, who achieved a top-to-south-base-camp descent in 2000, and Kit DesLauriers of the United States, who etched her name in the annals of Everest history in 2006.

The treacherous North Face has also been the stage for daring descents. In 1996, Italian mountaineer Hans Kammerlander skied down this face, followed a decade later by Swede Tomas Olsson and Norwegian Tormod Granheim. Unfortunately, their 2006 joint venture ended in tragedy when Olsson’s anchor broke while rappelling down a cliff in the Norton couloir at around 8,500 metres, resulting in a fatal fall. Granheim, despite the tragedy, continued his descent to Camp III. Similarly, Marco Siffredi, a pioneer in Everest snowboarding, met his untimely demise in 2002 during his second snowboarding expedition. These ventures underscore the enticing allure and inherent dangers of engaging in extreme winter sports at the world’s highest peak.

Airborne Adventures: Gliding and BASE Jumping

Mount Everest has served as a launchpad for several pioneering gliding adventures, adding a new dimension to the exploration of the world’s highest peak. Gliding descents, celebrated for their rapid transit to lower camps, have been gaining popularity amongst the extreme sports community.

In 1986, Steve McKinney etched his name in Everest’s history by becoming the first person to fly a hang-glider off the mountain. Another significant feat followed this bold endeavour in 1988 when Frenchman Jean-Marc Boivin performed the first paraglider descent from Everest. He embarked from the southeast ridge, swiftly descending in mere minutes to a lower camp.

These pioneering efforts inspired further endeavours. In 2011, two Nepali adventurers took to the sky, paragliding from the summit of Everest. They descended a staggering 5,000 metres in 45 minutes, an achievement that demonstrated not only the exhilarating speed of gliding descents but also the boldness of the human spirit.

Adding to the range of aerial adventures, on 5th May 2013, Valery Rozov undertook a daring BASE jump sponsored by Red Bull. Wearing a wingsuit, he leapt off the mountain, setting a record for the world’s highest BASE jump. Everest, thus, continues to be a towering playground for extreme sports, continually pushing the limits of human endurance and audacity.

Environmental Crisis: Impact of Commercial Climbing

Climbing Everest has undoubtedly become a landmark achievement for adventurers worldwide. However, this significant rise in popularity has had severe environmental implications. The president of the Nepal Mountaineering Association reported in 2015 that pollution, particularly human waste, has reached alarming levels, with about 12,000 kg of excrement left on the mountain each season.

These waste materials are often carelessly strewn around sleeping areas and common routes, thus transforming the pristine snowscape into a hazardous field. The situation escalates with the addition of other waste forms like spent oxygen tanks, abandoned tents, and empty cans, contributing to the mountain’s litter issue. To curb this, the Nepalese government now mandates every climber to descend with at least eight kilograms of their waste.

Mount Everest’s Base Camp, the buzzing hub of acclimatisation and rest, is the only location where climbers can relieve themselves without contributing to the mountain’s pollution. Expeditions now employ toilets fashioned from large blue plastic barrels, offering some semblance of waste management.

The human footprint on Everest extends beyond the waste left by climbers. Overcrowding during the peak climbing season, which sees more than 600 summit attempts, creates a bottleneck at the summit and along popular routes. Coupled with the high volume of visitors in the Sagarmatha National Park, the natural environment is under enormous strain. Deforestation to accommodate tourists, erosion of footpaths, and a vast quantity of waste jeopardise the park’s status as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Climate change has further aggravated the issue, with receding snow and ice revealing even more decades-old rubbish. This trash influx poses a significant health risk for residents within the Everest watershed, an essential water source for surrounding communities. With no waste management or sanitation facilities, this watershed is increasingly contaminated, potentially facilitating the spread of deadly waterborne diseases such as cholera and hepatitis A. The Everest ecosystem is reaching a critical point, and preserving this majestic landscape is becoming a monumental challenge in its own right.

Everest’s Ecosystem: Flora and Fauna at High Altitudes

Mount Everest, a natural wonder, is not only renowned for its towering heights but also for the unique ecosystem it nurtures within and around its slopes. The mountain’s lower regions are home to a variety of vegetation, including birch, juniper, blue pines, firs, bamboo, and rhododendron. Interestingly, a particular herb species, Saxifraga lychnitis, identified as the highest-altitude vascular plant, thrives on Everest’s slopes up to an altitude of 21,260 feet (6,480 m).

The rich biodiversity extends to animal life inhabiting areas below 16,400 feet. Species like the musk deer, wild yak, red pandas, snow leopards, and Himalayan black bears can be found. The region also hosts small populations of Himalayan tahrs, langur monkeys, hares, mountain foxes, martens, and Himalayan wolves.

As the altitude increases, life forms become sparse. However, a type of moss found at 6,480 meters and an alpine cushion plant called Arenaria growing below 5,500 meters underscore nature’s resilience. In fact, recent satellite data suggests vegetation expansion in areas previously considered barren.

Mount Everest also hosts the Euophrys omnisuperstes, a tiny black jumping spider found as high as 6,700 meters, likely the highest non-microscopic permanent resident on Earth. The base camp area is home to its cousin, the Euophrys everestensis, which survives on frozen insects carried by the wind.

Even at high altitudes, birds such as the bar-headed goose and the chough have been observed, with the latter spotted at 7,920 meters at the South Col. It’s worth noting that George Lowe, a member of Tenzing and Hillary’s 1953 expedition, reported seeing bar-headed geese flying over Everest’s summit.

Among the most recognized fauna in the region are the yaks, frequently used for hauling gear due to their robust physical adaptations. Other noteworthy species include the Himalayan tahr, prey to snow leopards, and the Himalayan black bear. Red pandas also roam the region, contributing to its biodiversity. Recent expeditions have discovered new species, including a pika and ten new species of ants, indicating that Everest continues to hold fascinating ecological surprises.

Climate and Meteo on Mount Everest

Climate Change: The Imminent Relocation of Base Camp

The climate change impact on Mount Everest is increasingly becoming a concern for expeditions. Khumbu Glacier, the site of the base camp for Nepalese Everest expeditions, is witnessing rapid thinning and destabilization. This progression, driven by climate change, has made the area less safe for climbers. In response, a committee formed by the government of Nepal to oversee mountaineering activities in the Everest region has recommended a shift in the location of the base camp to a lower altitude. Taranath Adhikari, the director general of Nepal’s tourism department, supports this change.

While this move would increase the distance between the base camp and Camp 1, thereby adding to the climbers’ challenge, it would considerably enhance safety. Despite these concerns, the current base camp remains functional for now and could serve its purpose for another three to four years. Nonetheless, as per official sources, a relocation could occur as soon as 2024, highlighting the escalating urgency of climate change considerations in mountaineering operations.

Decoding the Summit’s Weather Mysteries

Mount Everest’s extreme altitude poses unique meteorological challenges, and in 2008, a significant step was taken to understand and monitor these conditions. A new weather station was established at about 8,000 metres (26,000 feet). Initial data recorded in May 2008 included air temperature of -17 °C (1 °F), relative humidity of 41.3%, atmospheric pressure of 382.1 hPa (38.21 kPa), wind direction of 262.8°, wind speed of 12.8 m/s (28.6 mph, 46.1 km/h), and global solar radiation of 711.9 watts/m². This station, orchestrated by the Stations at High Altitude for Research on the Environment (SHARE), runs on solar power and is located on the South Col.

Mount Everest’s height extends into the upper troposphere and penetrates the stratosphere, with air pressure at the summit typically about one-third of that at sea level. This makes the summit susceptible to the swift and freezing winds of the jet stream, which can reach speeds of 160 km/h (100 mph). A record-breaking wind speed of 280 km/h (175 mph) was observed at the summit in February 2004.

Such powerful winds pose significant hazards to climbers, potentially blowing them into chasms or, through Bernoulli’s principle, further lowering the air pressure and thereby reducing available oxygen by up to 14%. To evade these severe winds, climbers generally aim for a 7 to 10-day window in spring or fall, aligning with the start or end of the Asian monsoon season.