“Everest”, the cinematic marvel of 2015, is a biographical survival adventure film that meticulously recreates the harrowing events of the 1996 Mount Everest disaster. Under the directorial and production mastery of Baltasar Kormákur, with screenplay credits going to William Nicholson and Simon Beaufoy, the film takes viewers on a chilling expedition led by Rob Hall, portrayed by Jason Clarke, and Scott Fischer, brought to life by Jake Gyllenhaal. The ensemble cast, featuring stellar performances from Josh Brolin, John Hawkes, Robin Wright, Michael Kelly, Sam Worthington, Keira Knightley, Martin Henderson, and Emily Watson, breathe authenticity into this thrilling narrative. In a poignant gesture, the film is dedicated to the late British actress Natasha Richardson by Kormákur and production collaborators Universal, Walden Media, Cross Creek, and Working Title.

The film’s journey kicked off on a grand note as the opening spectacle at the 72nd Venice International Film Festival on September 2, 2015. Its theatrical release was on September 18, 2015, following its premiere in IMAX 3D in the UK on September 11. The film spread its wings internationally in various formats, including IMAX 3D, RealD 3D, and 2D, and had a limited IMAX 3D exclusive release in the United States, Canada, and 36 other countries. A wider release in the United States followed on September 25. The film’s captivating portrayal of the epic survival story was a commercial success, grossing $203 million worldwide over a $55 million budget, accompanied by a warm reception from critics.

Plot: Summit to Survival

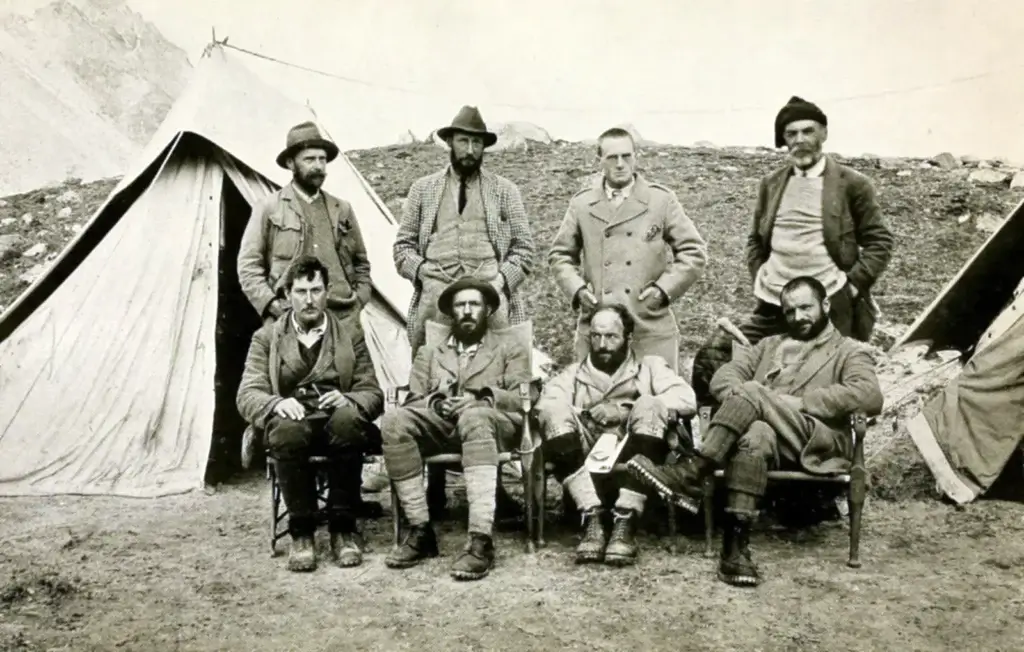

“Everest” follows commercial expeditions at Mount Everest’s base camp in May 1996. Two main groups, Adventure Consultants, led by Rob Hall, and Mountain Madness, directed by Scott Fischer, prepare to ascend. Climbers include Beck Weathers, Doug Hansen, Yasuko Namba, and journalist Jon Krakauer, with Helen Wilton overseeing Rob’s base camp. Rob promises his pregnant wife, Jan, he’ll return home in time for their baby’s birth.

As the climb progresses, Rob becomes concerned about overcrowding on the ascent route and partners with Scott to reduce delays. They start their summit attempt from Camp IV before dawn, aiming to descend by 2:00 PM for safety. However, uninstalled guide ropes and Beck’s vision problems cause delays, and Scott drops to help another climber despite Rob’s warning about overexertion risks.

Rob reaches the summit, joined by other climbers, including Yasuko. On the descent, he meets Doug, who is struggling but insists on pressing on. Their continued ascent exceeds the safe return time, leaving Doug exhausted and sick from the altitude. Scott also suffers from high-altitude pulmonary oedema — a blizzard strikes during their descent, depleting Doug’s oxygen tank. Doug detaches from the guide rope and perishes as Rob calls for more oxygen.

Scott’s condition worsens, and he asks to be left behind. Beck, still vision-impaired, gets lost with other climbers in the blizzard. Beck and Yasuko are left behind while others descend for help. An attempt to bring Rob more oxygen ends tragically when guide Andy ‘Harold’ Harris freezes to death. Rob succumbs to the cold after notifying Helen of Doug and Andy’s deaths.

The returning climbers alert the base camp about Beck and Yasuko, but severe weather prevents rescue. Surprisingly, Beck survives and returns to camp. After a helicopter rescue, he goes home severely frostbitten. The film concludes with Helen and Beck’s emotional homecomings, the birth of Rob’s daughter Sarah, and a reminder of Everest’s unforgiving nature.

Production of the Everest Movie

Development

Baltasar Kormákur helmed the directorial role for ”Everest”, meticulously executing scripts crafted by Simon Beaufoy and Mark Medoff. Justin Isbell and William Nicholson also provided the preparatory groundwork for the hands. The film, a product of Working Title Films, commenced shooting in November 2013 under the production supervision of Tim Bevan and Eric Fellner. Although Emmett/Furla/Oasis Films initially planned to co-finance the film, they withdrew from the project in October 2013.

Overcoming a minor setback in the production schedule, Cross Creek Pictures and Walden Media entered production on November 12, 2013, providing a crucial $65 million financing. Filming started in earnest on January 13, 2014, beginning in Italy’s Ötztal Alps and later transitioning to Nepal and Iceland. Further funding came from South Tyrol’s regional film board, contributing an additional $1 million.

A star-studded ensemble began in February 2013, with Christian Bale in talks to portray Rob Hall, the leader of Adventure Consultants. However, in July, Bale exited the project and the leading roles were eventually filled by Jake Gyllenhaal, Josh Brolin, Jason Clarke, and John Hawkes. Other additions to the cast during filming included Clive Standen, Martin Henderson, Emily Watson, Thomas M. Wright, Michael Kelly, Micah Hauptman, Sam Worthington, and Robin Wright. Their diverse roles ranged from playing seasoned expedition leaders and climbers, a caring base camp figure, an author, a filmmaker and mountaineer, to the concerned wife of a climber, thereby enriching the narrative texture of ”Everest”.

Filming

The ”Everest movie” occurred across several spectacular locations, commencing on January 13, 2014, in Italy’s Ötztal Alps. Brian Oliver, the co-financier, outlined the filming process as planned in three stages—six weeks in Italy, a month in Iceland, and another month in Nepal. To prepare for their roles, mountain climbing training was provided to actors Jake Gyllenhaal and Josh Brolin in the Santa Monica Mountains. The 44-member film crew then travelled to Kathmandu, Nepal, and secured permission for filming between January 9 and 23, with the Everest shoots starting on January 13, 2014.

The actors and crew dealt with several challenges during the shoot. As English actor Clive Standen described, the freezing temperatures made on-site filming difficult yet enjoyable. They filmed exterior shots at Cinecitta Studios in Rome to mimic Everest’s base camp’s bright sunlight. On April 18, 2014, a close call with disaster occurred. An avalanche hit Camp II on Everest, where the second unit crew was present. As a result, they had to halt production for a while. This tragic event led to the loss of 16 Sherpa guides. However, the film crew remained unharmed, with no injuries or fatalities.

The production team went to Pinewood Studios in the UK. Here, they recreated Everest elements against a greenscreen for future CG effects. These elements included Hillary Step, camp 4, icefall, and the summit. Salvatore Totino, the cinematographer, utilized SoftSun lights. His goal was to imitate the intense sunlight of Everest. The team cooled part of the set to 26-28 degrees Fahrenheit for authenticity. They also introduced real snow. These conditions helped Jason Clarke to portray Rob Hall enduring freezing temperatures realistically. The team captured the entire film with Arri Alexa XT cameras in the Arriraw format. This technique significantly boosted the film’s visual attraction.

Music

The musical score for the Everest movie was the work of Dario Marianelli. This score played a crucial role in creating the film’s atmosphere. The film’s soundtrack was filled with a wide range of tunes. These tunes mirrored the diverse experiences of the climbers, starting from their time in Nepal. Their journey through a busy Nepali market was vividly depicted. The Bollywood song “Yeh ladka hai Allah” underscored this depiction. This song is from the 2001 film Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham.

Music also solidified the film’s period setting, with songs like Sheryl Crow’s “All I Wanna Do” symbolic of the mid-1990s when the film’s events took place. Another notable inclusion in the soundtrack was “Weather with You” by Crowded House, further diversifying the film’s sonic landscape. Varèse Sarabande officially released the rich and immersive soundtrack of the Everest movie on September 18, 2015, thereby completing the auditory journey for audiences worldwide.

Release

The movie Everest had a carefully planned release strategy, with Universal Pictures initially scheduling it for a February 27 2015, debut in the United States and Canada. However, the release date was moved to September 18, 2015, marking the film’s exclusive release in IMAX 3D. A week after, on September 25, the film had a broader theatrical release. Everest became the first Universal Pictures film released in the Dolby Vision format in Dolby Cinema in the US and Canada.

In anticipation of its wide release, the film was presented at the 2015 CineEurope on June 23, held at the Centre Convencions Internacional Barcelona. This screening took place in full 3D Dolby Atmos, providing attendees with a captivating auditory and visual experience. The film’s world premiere was notable at the 72nd Venice International Film Festival. It was unveiled on September 2 2015, in the Sala Grande at the Palazzo del Cinema.

After enjoying a successful theatrical run, the adventure film ‘Everest’ was made available for home viewing, initially through DVD, Blu-ray, and Blu-ray 3D formats, released in January 2016. Catering to the desires of adventure film enthusiasts, the thrilling expedition could now be experienced in the comfort of their homes. Further enhancing the viewing experience, Universal Studios Home Entertainment released a 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray Disc edition of the film in September 2016. This pivotal release ensured that viewers could immerse themselves in Everest’s breathtaking visuals at the apex of available quality.

The Box Office Success of Everest Movie

The film Everest achieved impressive financial success, grossing $43.4 million in North America and $159.9 million in other territories. The global earnings amounted to $203.4 million, surpassing its production budget of $55 million. Everest also broke records, securing the most extensive September worldwide IMAX opening with earnings of $7.2 million, a feat that surpassed the previous record-holder, Resident Evil: Retribution.

Ahead of its wide release on 25 September 25 the United States and Canada, Everest had a limited debut in IMAX 3D and other premium large format screens across 545 theatres on 18 September 18his strategic early release resulted in earnings of $325,000 from late-night showings, eventually making $2.3 million on its opening day. The opening weekend saw the movie ranked at number five, earning $7.6 million. Notably, this broke the record for the largest IMAX September debut.

Everest expanded to 3,006 theatres, making an additional $4 million on its broad opening day. The movie garnered $13.09 million from the opening weekend, with a substantial $3.7 million coming from IMAX screens. This pushed North American IMAX revenue to $11.5 million, a first for any September IMAX release.

Released across 65 countries, Everest opened at number one in 12 countries, grossing $28.8 million from 5,154 screens. The movie continued to expand internationally, opening strongly in several markets. It grossed $5.2 million in Russia and the CIS. The United Kingdom, Ireland, and Malta contributed $4.9 million. In Mexico, it earned $4.4 million. The United Kingdom ($16 million) and Germany ($9.3 million) were key earners for total earnings. The film’s debuts in China and Japan increased its revenues, bringing in $11.3 million and $1.4 million, respectively. Overall, the mountainous adventure film demonstrated its box-office prowess, reaching lofty heights in its global release.

Critiques and Controversies: Critical Response

In film criticism, “Everest” garnered a respectable response. Aggregator Rotten Tomatoes shows a favourable rating of 73%, drawn from 231 reviews, yielding an average score of 6.6 out of 10. The site’s consensus applauds the film’s ‘dizzying cinematography’, though it suggests the narrative covers less adventurous ground. Another notable critique aggregator, Metacritic, rates the movie at 64 out of 100 based on 39 reviews, indicating a generally favourable reception. The CinemaScore audience survey also shows approval, assigning the film an average “A” grade on its A+ to F scale.

Despite these positive reviews, Jon Krakauer, author of “Into Thin Air”, sharply criticized the movie. Krakauer pointed out fabricated details and defamation, expressing regret over Sony’s quick acquisition of the book’s rights. However, director Baltasar Kormákur refuted these critiques, claiming they didn’t use Krakauer’s first-person account as a source for the film and alleging discrepancies between Krakauer’s version and the actual events.