The Matterhorn, a menacing mountain

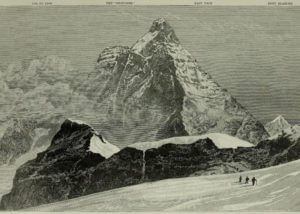

Around 1860, the most prestigious alpine summit, the most challenging and hard to access is the Matterhorn (Cervino).

It is an incredible mountain. At 4,478 m (14,692 ft), it is slightly shorter than Mont-Blanc but rises from the valley and enjoys a high prominence as well as isolation. It is isolated from other mountains and dominates all other summits around it.

It has some sort of menacing shape. At the time, everybody in the surroundings thought that the person who could achieve a successful ascent would need to be an exceptional being.

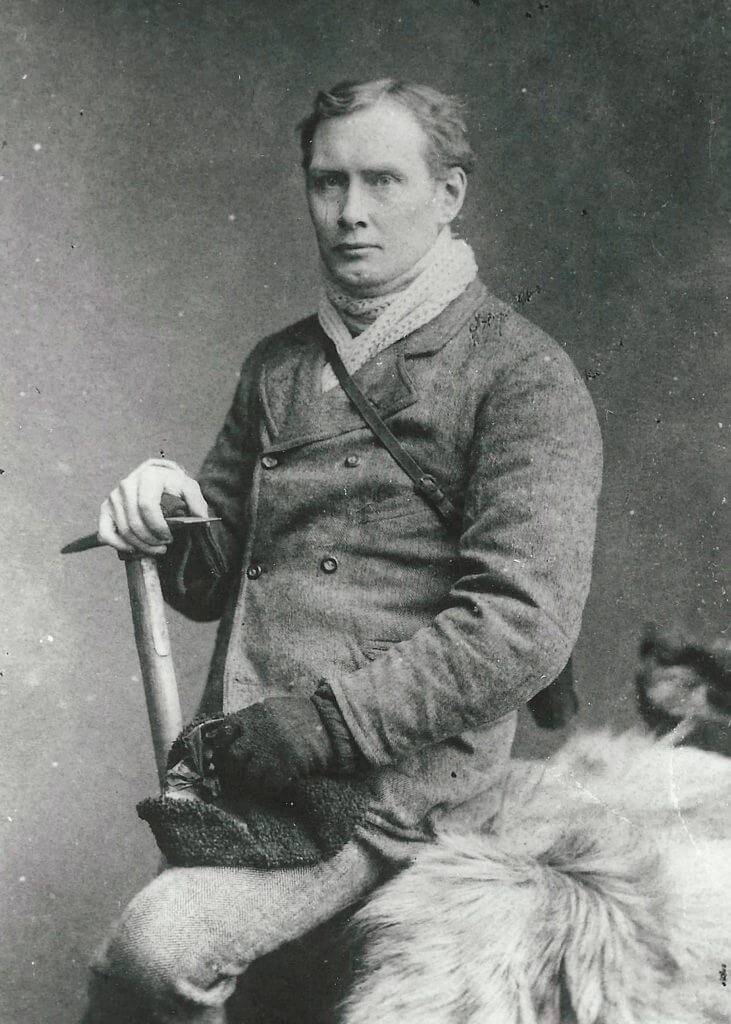

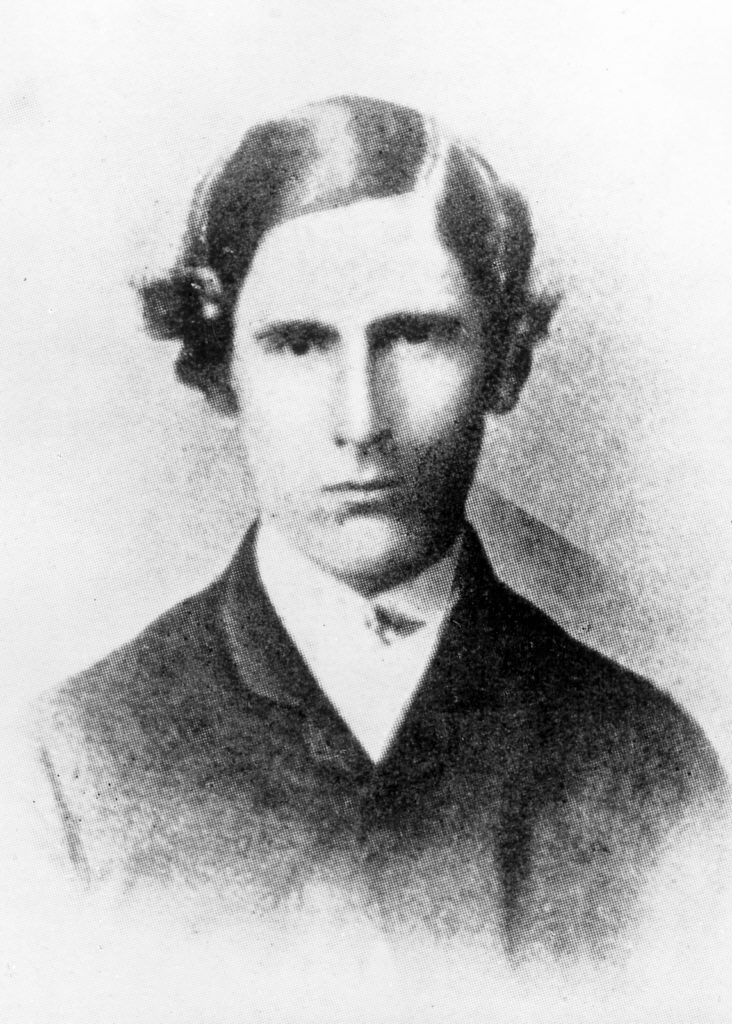

At the end of Spring 1860, an exceptional human being just booked a room at the Seiler Hotel in Zermatt. This extraordinary client is only 20 years old. He is neither tall nor powerful, but his deep blue-metallic look confirms his remarkable will. His name is Edward Whymper, an English man, son of the artist and wood engraver Josiah Wood Whymper.

The first attempt at the Matterhorn

E. Whymper was sent to the Alps as an engraver with a commission to complete a series of illustrations of high Alpine peaks. However, as soon as he sees the imposing shape of the Matterhorn, he knows that his life is tied to the mountain.

During his entire first stay, he studied the surroundings and the mountain and started training for the ascent.

It is the next summer, in 1861, that he attempted the first ascent. Like everybody before him, he started the climb from the south-eastern face of the mountain, which seemed to be the easier route. Because this face of the mountain is on the Italian side, Whymper stayed in Breuil (Cervinia) and had some trouble recruiting a guide and a team (people were scared of the mountain).

The small group went up a glacier, around the arête and pitched the tent. Around midnight, they heard a terrible sound coming from the top of the mountain. An enormous avalanche of rocks shook up the entire surroundings. By chance, nobody got hurt. They continued the climb early morning, to reach this sort of vertical tunnel, called the “chimney” at 3,825m. Concerned, the guide decided to stop the ascent. Frustrated, Whymper is forced to go back to London but decided to take his revenge the year after in 1862.

Jean-Antoine Carrel joins the party

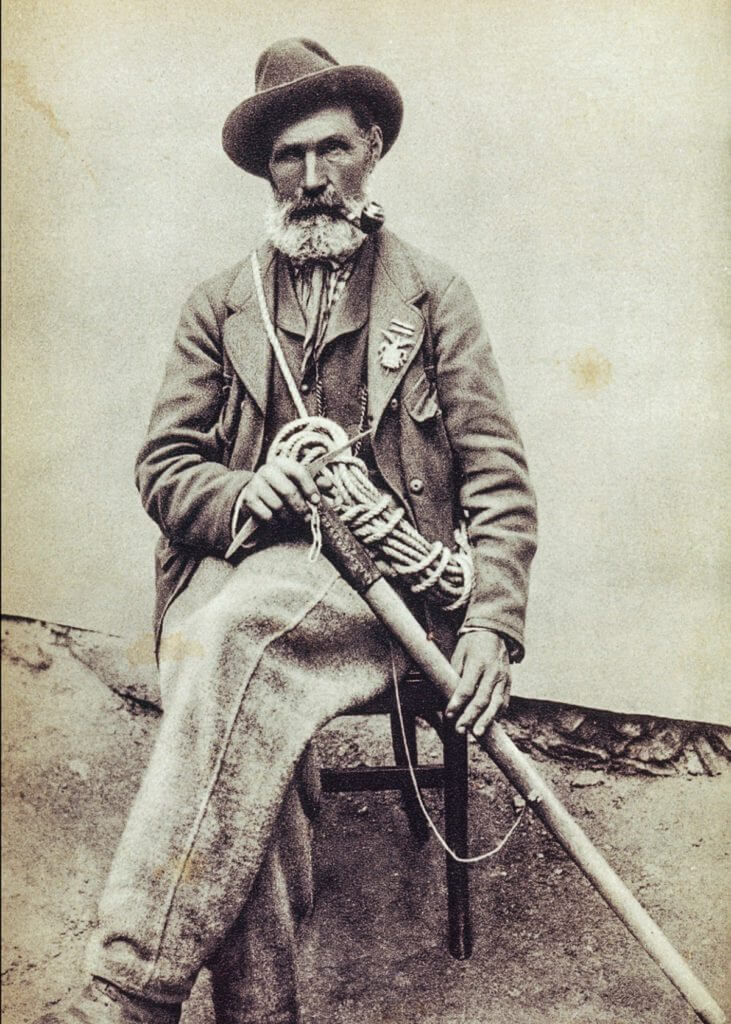

This year, a storm stopped E. Whymper’s second attempt. For the 3rd attempt, he recruited the best guide in the region and probably in the world, the Italian Jean-Antoine Carrel from Valtournenche.

They started the climb but, at 3,939m, another guide felt sick and forced them to stop and to go down. Whymper was desperate.

The group had left a tent and some equipment. Using this excuse, Whymper decided to go back on his own. He spent the night there. Continuing the climb solo, he reached the altitude of 4,084m.

He thought that the most challenging part was done and that he could go back down. On the descent, he tripped and fell on rocks with a vertical drop of 60 metres. By chance, a rock stopped him in his fall. He was wounded but safe and sound.

Despite his accident, Edward Whymper remained motivated and attempted the climb two more times.

The competition

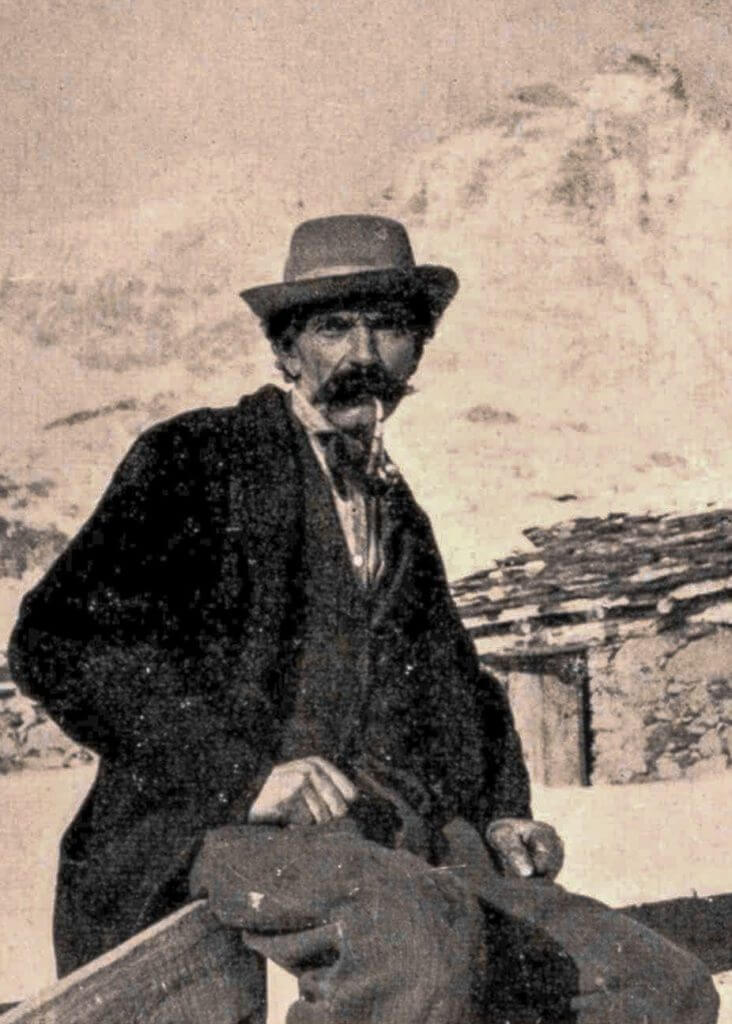

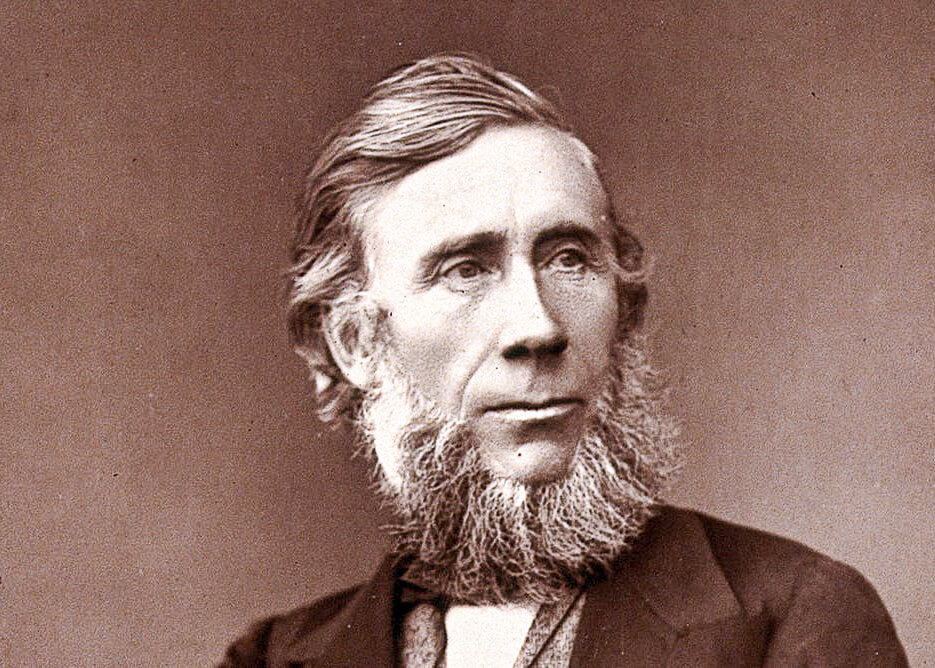

At the 5th attempt, Jean-Antoine Carrel stopped the climb one more time. The same year, Whymper heard that John Tyndall was attempting the climb….guided by Jean-Antoine Carrel.

From the valley, using a telescope, he observed Tyndall’s progress on the Matterhorn. Sure that Tyndall will reach the summit, Whymper is destroyed and desperate. His life is suddenly empty.

But, following Carrel’s recommendations, John Tyndall turned back, close to the summit. Whymper immediately came back from the dead.

Tyndall will then claim everywhere that the Matterhorn is inaccessible and that tempting the ascent is crazy.

The new route

Nationalism

The competition for the summit became stronger and stronger.

In the 1860s, Nationalisms are vigorous, even more so in Italy that is becoming one important unified country and nation. Italians now see the Matterhorn / Cervino as theirs. The mountain becomes a symbol.

E. Whymper came back to the Matterhorn in the summer of 1865. He changed his plans. After failing multiple times, he now believes that the climb from the south-east was a wrong route. He is convinced that the best way is from the north-east, from the Swiss side. Instead of staying in Italy, in Breuil-Cervinia, he stayed at Seiler, in Zermatt.

What appears to be a vertical wall may not be steeper than other sides or routes. At the same time, because of the geological formations of the mountains, there should be “natural stairs”. The ascent could be more accessible.

Whymper introduces his plans to Carrel. He manages to convince him, but two days later, Whymper sees Carrel leading a small caravan of carriers. Carrel remains evasive in his explanations.

The treason

On July 11th, Carrel leads a team of Italians to attempt the ascent. Whymper is disgusted but, at the same time, thinks that if he is travelling light and climbing from the eastern face, he could pass the Italians and reach the summit first.

He decides to hire Michel Croz, a young guide from Chamonix. Unfortunately, M. Croz is already committed to another client and needs to decline the proposition.

E. Whymper meets a fellow countryman, Lord Douglas. Lord Douglas is accompanied by the guide Taugwalder. They decide to go back to Zermatt together.

In Zermatt, by chance, Michel Croz is now free from his obligations and waiting for Whymper. Another English man, Charles Hudson, is with him.

The group decides to attempt the climb from the eastern face. Charles Hudson insists on adding the 19-year-old Douglas Robert Hadow to the team. E. Whymper is not keen on the idea of having a novice mountaineer in the group. At the same time, the Italians are seen relatively close to the summit so Whymper accepts the young Hadow.

Matterhorn – the final attempt

The race

The expedition leaves on Thursday, July 13th, 1865, at 5:30 am.

The group is composed of 8 members: the guide Peter Taugwalder and his two sons, the guide Michel Croz, Lord Douglas, Robert Hadow, Charles Hudson and Edward Whymper.

For the first day, the group decides not to climb too high. They reach the top of the Hörnli ridge around 11:20 am. The climb properly starts there. They are at around 3,450m and decide to set up the camp. Croz and the elder of the Taugwalder sons decide to continue and scout further away. When they come back, they are euphoric: the path is excellent and much less vertical than expected. The two affirm that if the entire group had tagged along, they could have reached the summit and come back before the sunset.

First to the summit of the Matterhorn

Anxious that the Italians may reach the summit first, the Whymper expedition continues the climb early. The group reaches 3,900m. They will then take a short 30min break. At 4,300m they will take another break. No Italian in sight, Whymper starts to smile.

The alpinists know that at Seiler, everybody must have their telescope and follow their progression.

It is the last part of the climb. Michel Croz takes the lead; they progress quickly. Croz and Whymper are together in the front. Behind Reverant Hudson on his own, showing excellent mountaineering skills. The young Robert Hadow is struggling, often asking for help.

Finally, the slope flattens. Whymper and Croz accelerate and reach the top together. On July 14th, 1865, they conquered one of the most difficult alpine summits.

Whymper wrote, “One crowded hour of glorious life”.

The descent, the tragedy

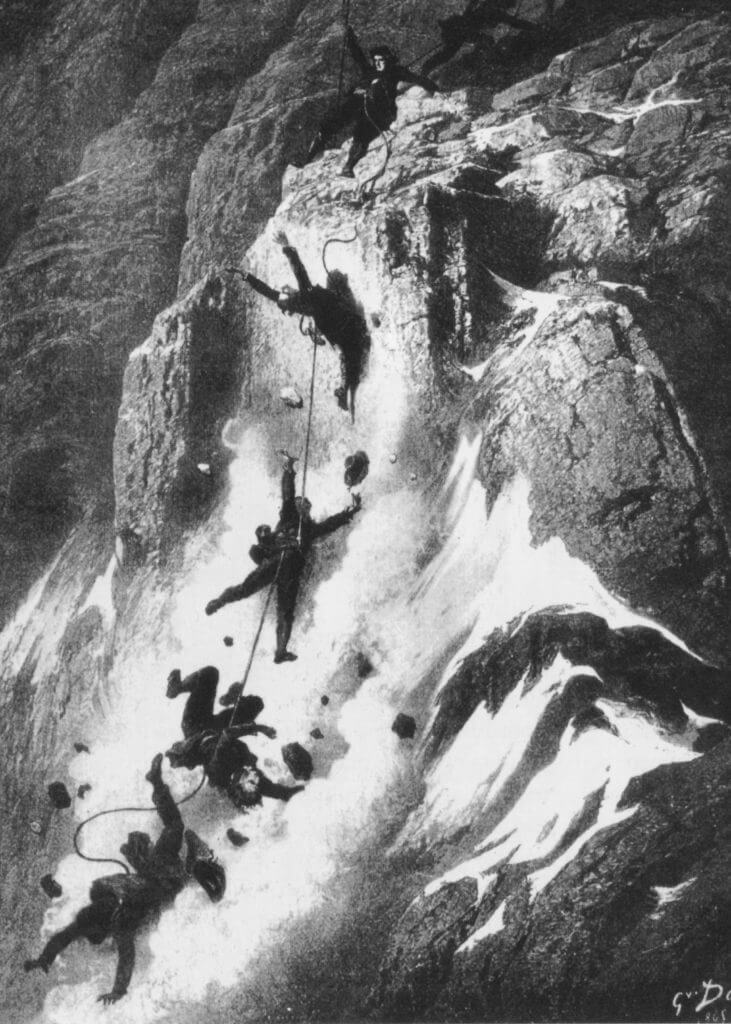

Croz, Hadow, Hudson and Douglas are roped up. Whymper and the Taugwalders follow them. The descent is not easy and is too tricky for Hadow. Croz tries to help him but unfortunately, the young novice slips and falls.

He drags along Croz, Douglas and Hudson. The four of them are hanging in the void, above the 1,200m precipice, while The Taugwalders and Whymper hold firmly.

Suddenly, the rope snaps and the four alpinists Croz, Hadow, Douglas and Hudson fall to their death. There will only be three survivors.

It is said that once back in Zermatt, Whymper barely greeted the Taugwalders. His most considerable pain immediately followed his deep feeling of happiness.