Majestic and legendary, the Drus, two peaks of a mountain in the prestigious Mont-Blanc massif in Haute-Savoie, stand proudly to reach dizzying altitudes.

This mountain is split into two distinct peaks: the Grand Dru, the highest, reaching 3,754 m, and the Petit Dru, slightly lower at 3,730 m. Overlooking Montenvers, the Petit Dru is particularly notable for its vertiginous granite face, one of the steepest in the Alps, with an impressive height of 1,000 m and an average slope exceeding 75°.

Located in the heart of the Mont-Blanc massif, the Drus mountain stands out for its visibility from the famous town of Chamonix. These two peaks beautifully embody verticality, inaccessibility, and commitment, values every mountaineer must respect. The south face, less visible from the valley but less steep, offers a prime route for thrill-seekers with one of the most beautiful D-grade routes in the massif, the crossing from Petit to Grand Dru.

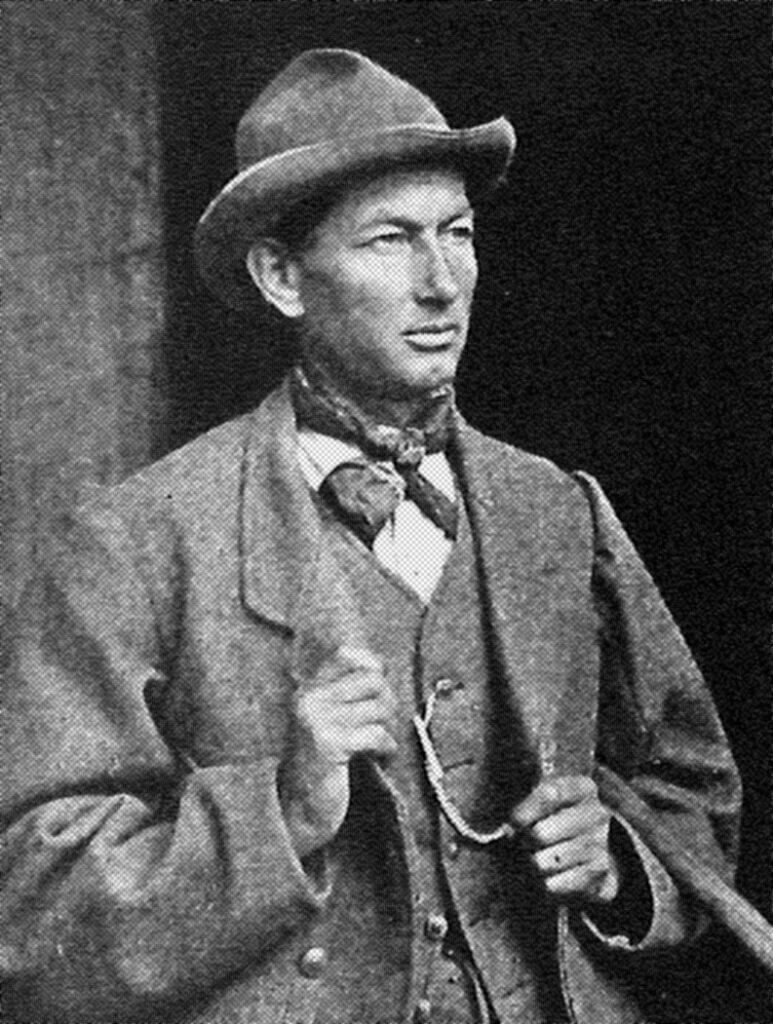

The Drus, whose two peaks compete in height with their respective 3,700 meters, are distinguished by their sharp silhouette, particularly that of the Grand Dru, shaped by numerous rockfalls throughout history. The first ascents of the Drus bear witness to their sporting challenge: the ascent of the Grand Dru in 1878 (C. Thomas Dent, J. Walker Hartley, A. Burgener and K. Maurer) and the ascent of the Petit Dru the following year (Jean Charlet-Straton, Prosper Payot and Frédéric Folliguet). These feats illustrate the courage and perseverance of mountain climbers, always ready to push the limits to reach the most impressive summits.

The Drus: A Look Back at Their History and Legends

The Drus: Chronicle of the Alpine Conquests of Mont Blanc

In the pages of mountaineering history, the Dru mountain in the Mont-Blanc range holds an honourable place. It has been the scene of numerous first ascents and treks, a perpetual invitation to push the boundaries of alpine exploration.

The first ascent of the Grand Dru took place in 1878, accomplished by Clinton Thomas Dent, James Walker Hartley, Alexandre Burgener, and K. Maurer. The following year, the Petit Dru was conquered by Jean Charlet-Straton, Prosper Payot, and Frédéric Folliguet.

In 1887, a courageous team of mountaineers comprising François Simond, Émile Rey, and Henri Dunod made the first crossing from the Grand to Petit Dru, using long ropes and taking the North face.

Pierre Allain and Raymond Leininger accomplished the first ascent of the north face in 1935, while the first winter crossing of the Drus was carried out by Armand Charlet and Camille Devouassoux in 1938. The same year, Laurent Grivel and Mr. and Mrs. A. Frova stood out by making the first ascent of the southeast face of the Grand Dru.

Over the years, more feats have been accomplished. In 1952, André Contamine and Michel Bastien climbed the south pillar of Grand Dru. In 1961, Robert Guillaume and Antoine Vieille made the first winter ascent of the Bonatti Pillar.

The year 1964 saw the first winter ascent of the north face of Petit Dru by Georges Payot, Yvon Masino, and Gérard Devouassoux. In 1967, Yannick Seigneur, Michel Feuillerade, Jean-Paul Paris, and Claude Jager made a direct ascent of the north face in winter.

The first solo ascent of the north face of the Grand Dru was accomplished by Joël Coqueugniot in 1969. Two years later, Jean-Claude Droyer successfully made the solo ascent on the direct Hemming-Robbins route.

In 1974, Walter Cecchinel and Claude Jager made the first ascent and first winter climb of the northeast corridor of Les Drus. In 1976, Walter Cecchinel and D. Stolzenberg were the first to achieve the winter ascent of the north face of Les Drus Pass.

Finally, let’s mention a unique adventure: in 1913, a group of mountaineers set out to install a hollow aluminium statue of the Virgin of Lourdes, weighing 13 kilograms and measuring almost a meter high, on the Petit Dru. Unfortunately, bad weather forced them to leave it at around 3,000 meters above sea level. It wasn’t until after the war, in 1919, that the statue was finally placed and sealed at the top. An image that adds an even more mythical and sacred dimension to this mountain.

West Face of the Drus: Story of a Conquest, from Triumph to Resilience

When Pierre Allain faced the North face of the Drus, he conjectured that the West side would remain forever impregnable. However, as early as 1952, the impossible was challenged by A. Dagory, Guido Magnone, Lucien Bérardini, and M. Lainé, who managed to climb it in two consecutive assaults, requiring the intensive use of artificial climbing techniques. This moment marked the start of a new chapter in the history of the Drus.

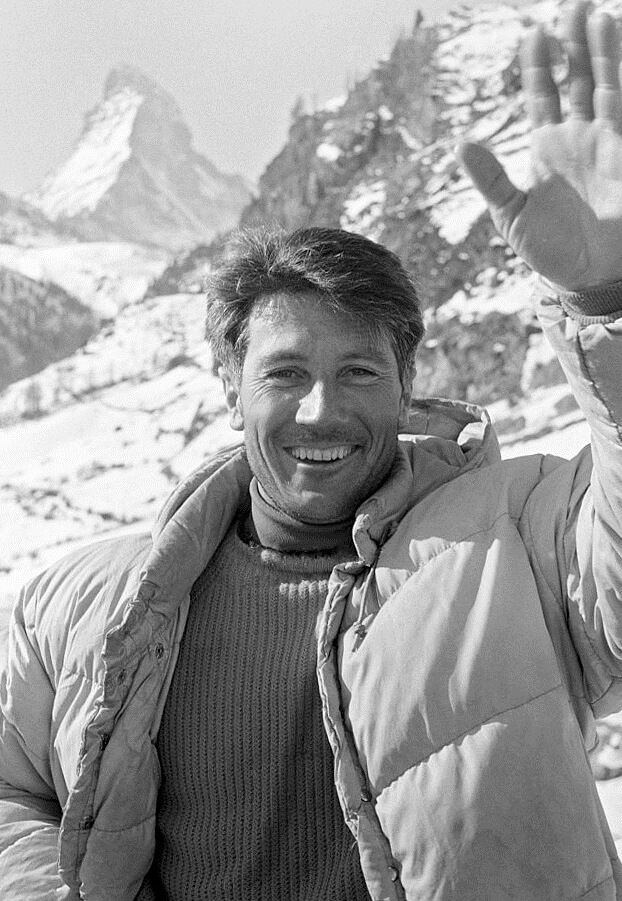

In 1955, Italian mountaineer Walter Bonatti accomplished an unprecedented feat by solo climbing the Southwest Pillar during a five-day ascent, hailed as one of the greatest achievements in mountaineering history. Jean-Christophe Lafaille, in 2001, pioneered a new route solo, also employing artificial climbing techniques.

In 1962, Gary Hemming and Royal Robbins, two American climbers, pioneered a major variant route leading directly from the base of the face to the stuck block, where it joins the 1952 route. Named the “American Direct”, this route became a great classic. Three years later, Royal Robbins, this time accompanied by John Harlin, charted another direct route that was extremely difficult and rarely repeated, right in the centre of the face.

René Desmaison, a renowned French alpinist, also made a significant mark in the history of the West face of the Drus through his notable ascents: the fourth ascent of the original route with Jean Couzy in 1955, the first winter ascent with the same partner in 1957, and finally, the first solo ascent in 1963, again via the classic route.

In the 70s and 80s, the inherent quality of the initiated climbing took precedence over the layout of the opened route. Thomas Gross is known for his perseverance, spending about fifty days on the West face of the Drus to force the passage no matter the cost.

Several other “routes” further enrich this history, including the “folding seats of paradise” by the Remy brothers (1980), the “route of the Genevans” by Nicolas Schenkel and B. Wietlisbach (1981), and the “French direct route” opened by teams from the High Mountain Military School in 1982. On the other hand, Michel Piola and Pierre-Alain Steiner marked a remarkable route on the left side of the face, named “cardiac passage”, between 1984 and 1986.

In 1991, Catherine Destivelle made a notable entry into mountaineering history by single-handedly opening a high-difficulty route, which now bears her name. Jean-Christophe Lafaille and Marc Batard added two other solo routes.

Subsequent landslides erase most of these routes, leaving only the paths on the far left of the wall intact. These events allow new routes to emerge once the rock is stabilized. Audacious Valery Babanov and Yuri Koshelenko ventured into the critical zone a few months after the 1997 landslide to establish a new transient route.

After the second wave of landslides (2003-2005), Martial Dumas and Jean-Yves Fredriksen opened a new route on this untouched face in 2007. In February 2021, four Military High Mountain Group climbers opened a winter route named BASE and shared this adventure in real time on YouTube for four days.

The Drus Facing Erosion: Landslides and Transformations of an Alpine Icon

Dominating the landscape, the west face of the Drus presents itself as a towering pyramidal wall more than a thousand meters high. This face is the scene of intense erosion, causing recurrent massive landslides. Nine have been recorded between 1905 and 2011, resulting in the fall of more than 400,000 cubic meters of rocks. The erosion, starting at the base and extending towards the summit, probably began at the end of the Little Ice Age in the 18th century. The eminent Bonatti pillar, once peaking at 500m, is now just a memory. The major landslide of 2005 represents nearly three-quarters of the total volume that collapsed in the last century and a half.

The first landslide of this period was triggered by the Chamonix earthquake, which occurred on August 13, 1905, with a felt intensity of VI on the MSK scale. The landslide of 1950, coinciding with a period of heatwaves during the summers of 1942 and 1943, highlights the potential role of climate change in the magnitude and frequency of these incidents.

Significant landslides also occurred in 1997, 2003, 2005, and 2011, during which climate warming might have played a major role. These events significantly altered the mountain’s structure and erased many historical climbing routes. The 2005 landslide, the most significant of the period studied, was caused by an exceptionally hot summer, accompanied by heavy rains, on a cliff already weakened by the heatwave of 2003. The fallen rocks cover an area of 90 to 95,000 m2 on the Drus glacier, with a thickness of 5 to 10 meters. Lesser landslides, totalling 10,000 to 12,000 m3, took place on September 10th and 11th, 2011, as well as a 60,000 m3 landslide on October 30th, 2011.

Crossing the Drus: Ultimate Alpine Adventure Guide

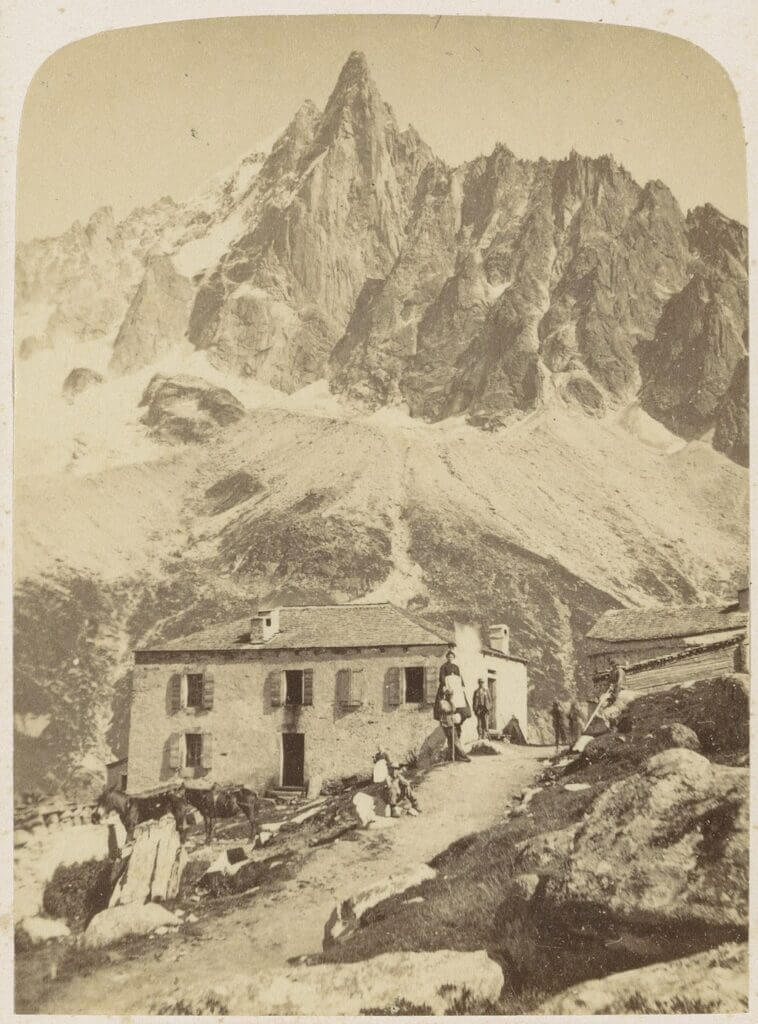

Approach, from the Montenvers Train to the Charpoua Refuge

Embark on the Montenvers train and continue your exploration by climbing the Mer de Glace up to the Moine needle, an adventure of about an hour and a half. In 2016, a renovated access was created for the Charpoua Refuge, perched at 2,841 meters. This route connects to the Balcony trail of the Mer de Glace, marked with ladders, handrails, and yellow rectangles. This climb, starting at 2,060 meters and culminating in a junction with the trail at 2,380 meters, offers you an ascent of 320 meters.

Next, take the Balcon Trail, which will lead you slightly backwards, to reach the Charpoua Circus in an hour and a half. In total, expect a hike of 4 to 6 hours from the Montenvers station—a true immersion into the heart of the splendours of the Mont-Blanc Massif.

The Crossing of the Drus – Route

This alpine route offers a difficulty rating of D, V+/A0, spanning 900m, typically completed in three days. From the refuge, climb the knob of La Charpoua up to approximately 3,000m altitude (25-30 min), then cross the glacier using the highest route to avoid major crevasses.

At an elevation of about 3,050m, follow a long horizontal ledge at the bottom of the south face. Follow it to the left until you reach two gullies. Climb up the terraces of the left gully, which, over a distance of 200m, leads you to the south-west ridge of the Stone Flames.

A few meters below the ridge, a rock pinnacle (3,361 m) is bypassed on the right at the level of a square gap and a chimney that you climb by starting from the left.

Continue by lightly pulling towards the left until you reach a shoulder that marks the actual beginning of difficulties (IV+ to V+).

Follow the ridge, which becomes less and less distinct due to a series of ledges, chimneys, and cracks, on the right at the beginning, then towards the west side in hidden gully chimneys.

About fifty meters from the summit, follow a ledge to the right, climb back to the left to bypass the corner and join a corridor that leads to the summit at the level of the Virgin. This should take between 5 and 7 hours from the refuge.

Join the Drus breach (3,697 m) by descending the Charpoua slope, then climb up to the Grand Dru through a small and short crack (V) leading to a ledge.

Follow this turn to the right for 10 m, then, via a flake, a crack, and a slab, return to the left.

Switching to the north side through the Z passage allows you to bypass the overhang on the left via a goat rake.

Above the north corridor, ascend a crack (IV), then a long uncomfortable chimney (6a, rope with knot installed, count 1h30 for this traverse) and exit to the left. This route is a demanding and thrilling climbing adventure, offering a truly breathtaking experience.

The Descent

From the summit of the Grand Dru, begin a descent of about 150 m along the east/northeast ridge, staying on the Charpoua side in the direction of the Col des Drus until you reach the edge of the ridge. At the entrance to the north couloir, look for terraces that you can access by down-climbing. You will find the first rappel near a small pinnacle topped by a block.

The following reminders follow in this way:

- A first 45m rappel brings you to the first terrace.

- Next, a 48m rappel down a broad green-tinted chimney leads you to a relay on a terrace to the left.

- A third 35m rappel along a spur leads you to a gravel ledge.

- Finally, a rappel of 50m on a smooth wall and on ledges takes you to a small spur.

Moving forward, you have two options in the hallway:

- The right side (48m + 45m + 47m + 50m shifted 20m to the right, followed by a bit of downclimbing).

- Or the left side (48m + 48m on a slab + 35m shifted to the left by 10m + 30m on a ledge).

A detailed map of this descent is available at the refuge for consultation.

Finally, cross the glacier, starting on the right bank and then going to the left bank until you reach the grove. From there, descend back to the Charpoua refuge. Plan for between 3 to 4 hours from the Grand Dru for this portion of the descent.