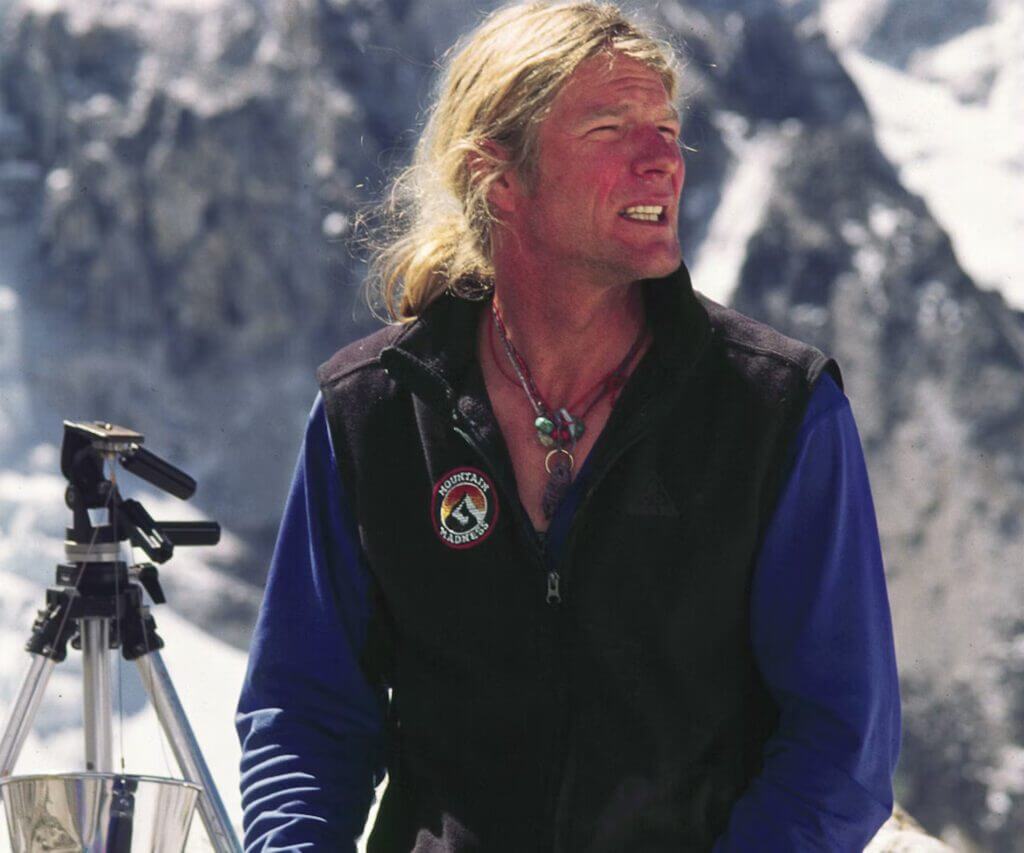

Who Was Scott Fischer?

Scott Fischer, born on December 24, 1955, was a celebrated American mountain climber, guide, and entrepreneur. In addition to founding the iconic guiding outfit Mountain Madness, he gained recognition for climbing the highest peaks on earth without supplemental oxygen. Scott Fischer joined Charley Mace and Ed Viesturs in successfully climbing K2 without oxygen. He and Wally Berg made history as the first Americans to reach the summit of Lhotse, the world’s fourth tallest mountain. Fisher first scaled Mount Everest in 1994 but unfortunately lost his life while guiding clients in the 1996 Everest Disaster.

Scott was raised in Michigan and New Jersey. His passion for mountains began after watching a documentary film with his father in 1970 about NOLS, the National Outdoor Leadership School. Impressed by the film, he visited the Wind River Range in Wyoming that summer and developed an unbreakable bond with the mountains. Fischer devoted the rest of his life to climbing peaks.

Mountain Madness

Scott Fischer co-founded Mountain Madness with Wes Krause in 1984 after relocating to the Pacific Northwest with his wife. They established the company in the vicinity of the Cascade and Olympic mountain ranges, providing ample guiding opportunities for the Seattle-based team. Quickly expanding to international adventures, Scott’s expertise as a seasoned climbing instructor and natural leadership skills made him well-suited to run the company. He believed that the challenge and discovery of mountaineering could positively impact people’s lives. His guiding and mentorship style reflected this, and he inspired others with his strength, determination, good humour, and can-do attitude. He passed this same approach down to everyone he climbed mountains with, including his two children.

Scott Fischer and Mountain Madness were part of the 1993 Climb for the Cure on Denali, organized by Princeton students to raise funds for AIDS research. In 1996, Fischer and Mountain Madness guided a Kilimanjaro expedition in another effort to raise funds for charity.

After Fisher’s Death, Kieth and Christine Boskoff assumed control of Mountain Madness. Together they invested heavily in the company, salvaging it from the brink of financial ruin. Tragedy struck once again in 1999 when Kieth suddenly died. Just seven years later, Christine and her partner Charlie Fowler died while climbing in China. In 2008, Mountain Madness guide Mark Gunlogson took over operations and continued to run the company successfully. Scott Fischer’s legacy continues to thrive through Mountain Madness. The company’s philosophy aligns with Fischer’s vision of delivering quality guiding and instruction while still having fun in the mountains.

The 1996 Everest Disaster

Mountain Madness organized an attempt to summit Everest for the 1996 season with Scott Fischer at the helm. In addition to the pressure of leading a successful push to the summit, Fischer was competing against another guided outfit. New Zealander Rob Hall’s Adventure Consultants were also making a summit bid. In retrospect, many mountaineers have attributed this ‘rivalry’ to the risky decisions of both lead guides.

Fischer spent the day leading up to the summit push helping an ailing climber descend from Camp 1. Fisher was slow to ascend to Camps 2 and 3. Ultimately, the team arrived on the summit of Everest at 3:45 p.m. on May 10th, nearly two hours after the hard deadline for a safe descent (2 p.m.). Rob Hall’s group also summitted well after the deadline. By this time, Fischer was unusually exhausted, perhaps due to his rescue in the days preceding the summit bid. He may also have been suffering from acute altitude sickness by the time the teams reached the summit.

Scott Fischer’s Death

As if on queue from the devil himself, a severe storm hit the mountain shortly after both teams began their descent, leaving the climbers stranded on the South Col without adequate shelter. Fischer remained at the South Col during the descent while the rest of his team reached the safety of Camp IV. Struggling to continue, he asked his climbing partner Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa to descend without him and send back Anatoli Boukreev for help. Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa and Boukreev managed to rescue several other climbers including the leader of the Taiwanese team, whom they found stranded with Fischer.

Although he was still breathing lightly, it was already obvious that Fischer was lost. The team chose to save Gao, the Taiwanese leader.

When Boukreev returned to assist Fischer, he was already dead. In fact, Boukreev found Fisher half undressed. Called ‘paradoxical undressing,’ this behaviour is commonly observed in the final stages of hypothermia. Boukreev shrouded Fischer’s body and moved it off the main climbing route. Scott Fischer’s body remains on the mountain to this day. The 1996 Mount Everest disaster is one of the deadliest in the mountain’s history, with 8 people losing their lives. Yet, no other climbers from Fisher’s team perished. In addition to the heroism of Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa and Boukreev, Fischer’s self-sacrifice ultimately saved the life of his clients and others on the mountain that day.

Mr Rescue

Metaphorically speaking, Fischer went down with the ship to save his crew in the 1996 Everest Disaster. However, that was not his first selfless act in the mountains. Even before the 1996 expedition, Fischer was known as Mr. Rescue for his assistance in numerous high-altitude rescues.

On K2, he and his team abandoned their summit bid to help rescue Aleskei Nikiforov, Thor Keiser, and Chantal Mauduit. Despite the arduous rescue effort, the team still managed to summit without supplemental oxygen just days after. On the same mission, the team helped Rob Hall and Gary Ball descend to safety after the two developed altitude sickness. Although it may seem callous to folks unfamiliar with the ardour of high-altitude climbing, rescues like these are difficult and uncommon. Oftentimes, climbers in need of assistance are left for dead. The effort of saving them is too difficult and risky in such a harsh environment. Scott Fischer was one of the few who was strong enough to assist. Those who knew him well say it was his love of people that pushed him to rescue his fellow climbers.

Fischer and his guiding outfit Mountain Madness assisted in many charity climbs over the years. Despite his status as a famous mountain climber, Fischer wasn’t particularly adept at running a profitable guiding outfit. His primary goal was always to provide clients with memorable experiences, not to make money off of them.