Mont Blanc is the pinnacle of the Alps and Western Europe, soaring to an impressive height of 4,806 metres (15,766 feet) above sea level. This majestic mountain, which marks the border between France and Italy, is the highest peak in the Alps and the tallest in Europe outside the Caucasus range. It ranks as the second most prominent peak in Europe, following Mount Elbrus, and holds the eleventh position in global prominence.

The mountain bestows its name upon the surrounding Mont Blanc massif, which extends across parts of France, Italy, and Switzerland. The summit of Mont Blanc itself is positioned at the watershed line between the Ferret and Veny valleys in Italy and the Montjoie and Arve valleys in France. This location has historically been the subject of ownership disputes between France and Italy.

Encircling Mont Blanc are three principal towns: Courmayeur in Italy’s Aosta Valley, and Saint-Gervais-les-Bains and Chamonix in France’s Haute-Savoie. Chamonix, in particular, holds historical significance as the host of the inaugural Winter Olympics. The region is a haven for outdoor enthusiasts, offering many activities ranging from hiking, climbing, and trail running to winter sports such as skiing and snowboarding. The Goûter Route, acclaimed as the most favoured path to the summit, typically requires a two-day journey.

Mont Blanc is not only a natural marvel but also a hub of human achievement and connectivity. The Mont Blanc Tunnel, spanning 11.6 km (7+1⁄4 mi), was constructed between 1957 and 1965 beneath the mountain, serving as a vital transalpine transport corridor. Additionally, a cable car facilitates an aerial passage from Courmayeur to Chamonix via the Col du Géant, bridging the majestic mountain range and offering unparalleled views of this alpine wonder.

Mont Blanc’s Climate: A Delicate Balance of Cold, Wind, and Variation in Precipitation

Nestled at the watershed between the Rhône and Po rivers, the Mont Blanc massif straddles the climatic divide between the northern and western Alps and the southern Alps. This unique positioning contributes to a climate that shares similarities with the northern side of the Swiss Alps, especially evident in the Mer de Glace area.

The climate of Mont Blanc is classified as cold and temperate (Köppen Cfb), a characteristic profoundly shaped by the massif’s elevation. As the highest point in the Alps, Mont Blanc and its surrounding peaks have the unique ability to generate their own weather systems. With increasing altitude, temperatures plummet, leading to a permanent ice cap at the summit, where temperatures hover around −20 °C (−4 °F). This elevation also subjects the summit to vigorous winds and rapid shifts in weather, making the area predominantly glaciated or snow-covered, enduring the brunt of icy conditions.

Precipitation patterns vary significantly with altitude across the Mont Blanc massif. The village of Chamonix, situated below Mont Blanc at an elevation of 1,030 metres (3,380 feet), receives approximately 1,020 mm (40 inches) of rainfall annually. In contrast, the Col du Midi, at an altitude of 3,500 metres (11,500 feet), experiences a much higher level of precipitation, with totals reaching 3,100 mm (122 inches). Interestingly, precipitation decreases near the summit, at around 4,300 metres (14,100 feet), where only about 1,100 mm (43 inches) is recorded, underscoring the complex interplay of altitude and moisture levels within the Mont Blanc region.

Disputed Summits: The Franco-Italian Controversy over Mont Blanc

The delineation of the border between Italy and France along the Mont Blanc massif has been a subject of contention for centuries, with its exact positioning near the summits of Mont Blanc and the Dôme du Goûter remaining disputed. Italian authorities argue that the border should follow the main Alpine watershed, which would divide the summits between the two countries. Conversely, French authorities maintain that the border circumvents these summits, allocating them entirely to France. This disagreement encompasses approximately 65 hectares on Mont Blanc and 10 hectares on Dôme du Goûter.

Historically, the entire region of Mont Blanc was part of the Duchy of Savoy until the French Revolution, when changes in sovereignty began to reshape the area’s political landscape. Following the acquisition of the Kingdom of Sardinia by Duke Victor Amadeus II in 1723, which later played a significant role in Italian unification, the French Revolutionary Army seized Savoy in 1792, integrating it into France. The 1796 treaty forced Victor Amadeus III to relinquish Savoy and Nice to France, establishing the border based on the highest points along the Piedmont side, although lower mountains obstructed visibility from Chamonix and Courmayeur.

The Congress of Vienna post-Napoleonic Wars restored the traditional territories of Savoy, Nice, and Piedmont to the King of Sardinia, nullifying the 1796 Treaty of Paris. The annexation of Savoy to France was finalized in a legal act signed in 1860, with a subsequent demarcation agreement in 1861 marking the border along the watershed, placing Mont Blanc on the Franco-Italian boundary for the first time.

Despite these historical agreements, discrepancies arose with the publication of a French topographic map in the late 19th century by Captain JJ Mieulet, which deviated from the agreed watershed line, fuelling the ongoing dispute. Modern Swiss mapping acknowledges this contested territory, offering two interpretations of the border that either divide the summits between France and Italy or place them solely within French territory. NATO maps, drawing on data from the Italian Istituto Geografico Militare and reflecting treaties still in force, further illustrate the complexity of this territorial dispute.

How High is Mont-Blanc?

The elevation of Mont Blanc, Europe’s highest peak, is a subject of continuous study due to its thick, ever-changing dome of ice and snow. This variability means that while exact and permanent measurements of the summit’s height are challenging to ascertain, precise readings have been obtained at specific intervals. Historically, the mountain’s elevation was long held to be 4,807 metres (15,771 feet), until advancements in GPS technology in 2002 enabled a more accurate measurement of 4,807.40 metres (15,772 feet 4 inches).

The intense heatwave of 2003 prompted a comprehensive re-measurement by a diverse team, including glaciologist Luc Moreau, expert surveyors, mountain guides, and students. This effort revealed the summit had risen to 4,808.45 metres (15,775 feet 9 inches), showing a notable shift in its position. Following this, over 500 points were surveyed to understand the impact of climate change on the mountain’s physical stature, establishing a protocol for biennial measurements.

Subsequent assessments have revealed fluctuations in the summit’s height, with a notable measurement in 2005 indicating an increase to 4,808.75 metres (15,776 feet 9 inches) and later measurements in 2013 recording a peak at 4,810.02 metres (15,781 feet). These ongoing evaluations underscore the dynamic nature of Mont Blanc, directly linking its physical changes to broader environmental trends.

Moreover, the rock summit, distinct from the ice-covered peak, has been identified at 4,792 metres (15,722 feet), illustrating the complex topography of the mountain. From its summit, on a clear day, one can glimpse across vast distances, encompassing the Jura, the Vosges, the Black Forest, and the Massif Central, alongside the principal summits of the Alps, offering a panoramic view that spans the heart of Europe.

Scaling Mont Blanc: Challenges, Routes, and Preparation for Ascent

Essential Preparation for Climbing Mont Blanc: Training, Acclimatisation, and Safety

Annually, Mont Blanc attracts close to 20,000 mountaineering enthusiasts, with some days seeing as many as 500 climbers. The Goûter Route, known for its length but relative ease for those who are well-trained and acclimatised to high altitudes, is the most frequented pathway to the summit.

The realm of mountaineering, inherently remote and fraught with objective dangers, demands a profound understanding of high mountain environments alongside suitable physical and material preparation. Notably, the Goûter Route includes perilous segments such as the Goûter Corridor, notorious for rockfalls. The high altitude increases the risk of acute mountain sickness, which can be fatal, underscoring the importance of prior acclimatisation.

Mont Blanc’s popularity contributes to a higher incident rate compared to other alpine summits, with annual fatalities on the Goûter Route averaging between five and seven. In 2006 alone, the High Mountain Gendarmerie Platoon (PGHM) carried out 120 rescue operations, 80% of which were due to exhaustion from poor physical preparation or lack of acclimatisation; 30% of climbers sustained injuries such as frostbite or crampon wounds or suffered from altitude-related illnesses upon their descent. Despite a low success rate of 33% without a guide (improving to 50% with professional guidance), between 2,000 and 3,000 climbers reach the summit each year.

In response to the high failure rates, some agencies now offer beginners a few days of mountaineering courses, including an introduction to the sport, a period for altitude acclimatisation, and an ascent of Mont Blanc under the guidance of a professional mountain guide. This approach, marking a departure from traditional mountaineering philosophies that catered to experienced climbers familiar with alpinism techniques, is yet to confirm its effectiveness. It challenges the conventional view of mountaineering as a pursuit of experienced climbers, suggesting instead a trend towards trophy hunting rather than a rite of passage.

Key Routes to the Summit: Navigating Mont Blanc’s Climbing Paths

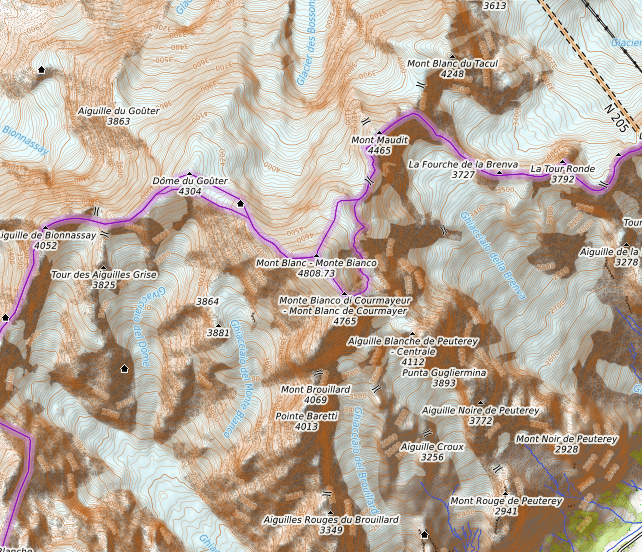

Mont Blanc, Europe’s highest peak, offers several classic climbing routes, each presenting its unique challenges and breathtaking scenery. The most traversed path, the Goûter Route, known for its accessibility via the Tramway du Mont-Blanc from Saint-Gervais-les-Bains, begins with an ascent towards the Refuge de Tête Rousse. This route is notorious for the perilous Goûter Corridor, where climbers face the risk of frequent rockfalls. The journey continues past the Vallot emergency cabin to the Dôme du Goûter, concluding at the summit along the arête des Bosses.

Another esteemed route is La Voie des 3 Monts, starting from Chamonix. This path involves a cable car ride to the Col du Midi, an overnight stay at the Cosmiques Hut, and a challenging climb over Mont Blanc du Tacul and Mont Maudit before the final ascent. This route is known for its technical difficulty and the additional challenge of conquering two other peaks en route to Mont Blanc’s summit.

For those seeking a historical approach, the Grands Mulets Hut serves as a base for the traditional French route, often chosen for winter ski ascents or summer descents to Chamonix. Conversely, the Italian side offers La route des Aiguilles Grises, beginning with a crossing of the Miage Glacier and a night at the Gonella refuge, followed by an ascent through the Col des Aiguilles Grises and the Dôme du Goûter.

Adventurers might opt for the Miage – Bionnassay – Mont Blanc crossing, a three-day expedition that is as enchanting as it is demanding, starting from Contamines-Montjoie and involving a traverse of ice and snow ridges at high altitudes.

Despite appearing straightforward, these routes demand significant physical preparation, acclimatisation to high altitudes, and mastery of mountaineering skills. The risks are real, as evidenced by the annual fatalities and the need for rescue missions, highlighting the importance of proper equipment, experience, or the guidance of a professional mountain guide. The challenge of Mont Blanc is not only in reaching its summit but also in safely navigating the mountain’s unpredictable conditions and respecting the rigorous demands of high-altitude climbing.

Mont Blanc’s Alpinism Legacy: From Early Expeditions to Modern Achievements

Mont Blanc: From Myth to Enlightenment

During the 17th century, amidst the Little Ice Age, processions and exorcisms were organized in an attempt to halt the advance of the Mer de Glace glacier, which was perilously encroaching upon Chamonix. Until the 18th century, valley inhabitants viewed the Mont Blanc massif with trepidation; its peaks were ventured upon only by a few chamois hunters and crystal seekers.

Despite this, the massif sparked the curiosity of the Genevan bourgeoisie, who, alongside English visitors, ventured to the Môle—a prominent viewpoint to the southeast of the city—to observe Mont Blanc more closely. However, the lack of maps detailing the internal layout of this segment of the Alps led to disorientation. A line drawn from Geneva, passing over the summit of the Môle towards the Rhône Valley, was supposed to locate Mont Blanc somewhere along its extension but invariably placed it north of the Chamonix Valley, contrary to its actual southern position. This misplacement persisted for half a century, a confusion that Charles Henri Durier attributed to the visibility of Mont Blanc from Geneva, which becomes obscured as one approaches the Alps. The first summits encountered upon departing from Bonneville are not Mont Blanc but the peaks of Morcle and Midi, especially the Buet, which lies north of Chamonix in the direction of Geneva towards the Môle and was mistakenly identified as the high mountain observed from afar. Consequently, the people of Geneva dubbed Mont Blanc “the cursed mountain,” a moniker that stuck due to geographic misunderstanding perpetuated by cartographers.

Durier notes that Mont Blanc was identified too late for myths or poetic symbolism to attach to it, marking its entry into an era of scientific rationalism directly. This shift reflects a transformation in the perception of Mont Blanc from a source of superstitious dread to an object of scientific interest and exploration.

Early Scientific Endeavours and Ascension Attempts on Mont Blanc

In the late 17th century, Jean-Christophe and Nicolas Fatio de Duillier were pioneers in estimating Mont Blanc’s height at 4,728 meters above the Mediterranean Sea, marking an early intersection of scientific inquiry and mountaineering. By 1760, the Swiss naturalist Horace Bénédict de Saussure initiated a series of excursions to Chamonix, driven by a fascination with Mont Blanc and determined to conquer its summit. Saussure’s ventures, especially alongside the Courmayeur guide Jean-Laurent Jordaney, known for his patience, laid foundational work in alpine exploration. Their efforts included attempts to chart a route through the Miage Glacier and Mont Crammont, aiming to unlock the secrets of the Alpine massif.

Further advancements came when George Shuckburgh-Evelyn, a newly minted member of the Royal Society, joined Saussure in 1775 to refine Mont Blanc’s altitude measurements using triangulation and barometric pressure from the Môle, leading to a revised elevation of 4,787 meters. These findings, adjusted in 1840 by engineer geographers to 4,806.5 meters, underscored the evolving precision in understanding Mont Blanc’s imposing stature.

Saussure’s promise of a reward for the first successful ascent in 1760 was a catalyst for serious attempts to scale Mont Blanc. Initial efforts by valley guides in 1775 via the Grands Mulets route were thwarted by harsh weather and exhaustion. Recommendations for subsequent expeditions included practical advice to mitigate the sun’s glare, reflecting the pragmatic challenges faced by early climbers. Marc-Théodore Bourrit’s engagement of three guides and Michel Paccard in 1783 further demonstrated the perilous nature of these early ascensions, often hampered by adverse conditions.

A significant attempt in 1784 by Paccard and another guide to ascend via the Aiguille du Goûter showcased the daunting obstacles climbers faced, from difficult terrains to unexpected snow accumulation. This period of exploration was marked by trial and error, with various expeditions, including a notable one by Saussure, Bourrit, and their companions in 1785, attempting to navigate through snow-laden routes without success.

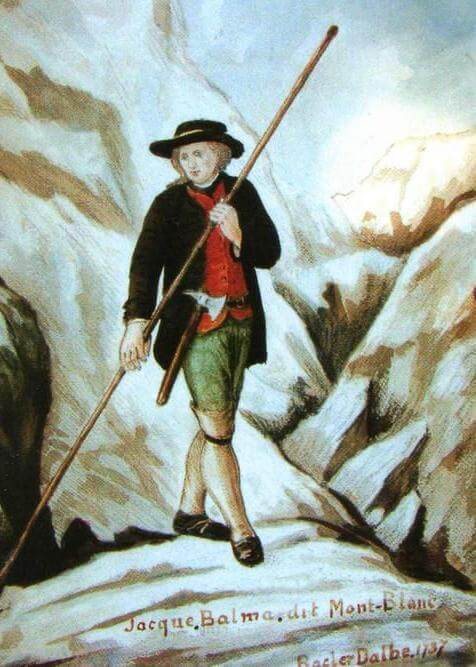

In a pivotal moment in June 1786, five Chamonix guides were divided into two groups to explore the most feasible approach to the Dôme du Goûter, an effort that underscored the collaborative spirit and determination of these early mountaineers. Despite facing insurmountable odds and the decision to retreat, Jacques Balmat’s unexpected overnight stay on the mountain became a testament to the resilience and adventurous spirit of those drawn to Mont Blanc. His safe return the following day not only surprised the valley’s inhabitants but also symbolized the enduring allure and formidable challenge posed by Europe’s highest peak.

Groundbreaking Ascents of Mont Blanc: Pioneers and Milestones

On the 7th of August, 1786, Jacques Balmat and Michel Paccard embarked on a covert journey from Les Bossons, camping atop the mountain of La Côte. They navigated the Grands Mulets route the following day, reaching the Grand Plateau by mid-afternoon. Their ascent took them eastward, over steep slopes above the Rochers Rouges Supérieurs, making them visible from the valley through the telescope of Baron Adolph Traugott von Gersdorf. By late afternoon, they had passed the Petits Rouges and the Petits Mulets, arriving at the summit at 6:23 pm, where they spent thirty-three minutes before beginning their descent. That night, they rested on the glacier, continuing their journey back to the village the next morning. Paccard, suffering from snow blindness, relied on Balmat’s assistance for the descent. Upon returning, Balmat was met with the sorrowful news of his daughter’s death, coinciding with the day they reached the summit. This monumental ascent is considered the dawn of modern alpinism.

Almost a year later, Horace Bénédict de Saussure, accompanied by nineteen individuals, including Balmat, succeeded in reaching the summit on the 3rd of August, 1787. Saussure’s expedition marked the first scientific measurement of Mont Blanc’s altitude directly from its summit, estimating it to be 4,775 meters after averaging three prior measurements.

Subsequent measurements in the 1820s by Plana and Carlini, and later corrections by engineer geographers, refined Mont Blanc’s altitude to 4,811.6 meters. These endeavours culminated with Commander Filhon’s calculation of 4,810.9 meters, leveraging earlier triangulation efforts.

Marie Paradis became the first woman to summit Mont Blanc on the 14th of July, 1808, a feat achieved under challenging conditions and with considerable assistance from her guides. Henriette d’Angeville followed as the second woman to reach the summit on her own accord on the 4th of September, 1838, dressed in a simple gown.

Until 1827, climbers predominantly followed the route established by Balmat and Paccard, from the Grand Plateau to the summit via the northern face above the Rochers Rouges. The Corridor route to the east later became a preferred path, connecting with the Trois Monts route at the Mur de la Côte. The Arête des Bosses, now the standard route to the summit, was not traversed until 1861, highlighting the evolution of mountaineering routes on Mont Blanc.

Tragedy and Triumph: The Formation of Mont Blanc’s Guide Companies

The first fatal accident on Mont Blanc occurred during its tenth ascent in 1820, an expedition later chronicled by Alexandre Dumas through the account of Marie Coutet, a guide who survived the ordeal. The expedition, comprising British Colonel Joseph Anderson and Dr. Joseph Hamel, a meteorologist for the Russian Emperor, faced adverse weather conditions. Despite this, the clients insisted on reaching the summit, a decision that led the thirteen guides to proceed. Their ascent, hindered by deep, fresh snow, ended tragically when an avalanche was triggered, sweeping away the leading three guides into a crevasse 200 meters below, where they perished. Their remains were discovered in 1861 at the base of the Bossons Glacier and were remarkably preserved.

The aftermath of this tragedy galvanized the mountain guides into unity. On May 9, 1823, a decree from the Chamber of Deputies of Turin, sanctioned by Charles-Félix of Savoy, officially established the Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix. The decree outlined a structured classification for guides: the first class consisted of experienced guides with the necessary skills for leading expeditions, the second class included less experienced guides primarily serving as porters, and a third category was designated for apprentice guides. By 2018, the company had grown to include over 220 professional members, encompassing both guides and medium mountain leaders.

Following in Chamonix’s footsteps, the Société des Guides de Courmayeur was established in 1850, becoming the first of its kind in Italy and the second worldwide after Chamonix. Its founding leader, Jean-Laurent Jordaney from Pré-Saint-Didier, had previously accompanied Horace Bénédict de Saussure on explorations of the Miage Glacier and Mont Crammont, as well as British mountaineer Thomas Ford Hill to the Giant’s Col in 1786. This development marked a significant milestone in the professionalization of mountain guiding, laying the groundwork for safer and more organized ascents of Mont Blanc.

Mont Blanc Milestones: Pioneering Ascents and Aviation Firsts

On July 15, 1865, an expedition led by George Spencer Mathews, Adolphus Warburton Moore, Horace Walker, Franck Walker, Melchior Anderegg, and Jakob Anderegg marked the first ascent of Mont Blanc via the Brenva Spur, setting a precedent for future climbers. This feat was followed by Isabella Straton’s pioneering winter ascent on January 31, 1876, with guides Jean Charlet-Straton, Sylvain Couttet, and porter Michel Balmat, further demonstrating the mountain’s year-round allure.

In 1892, Laurent Croux, Émile Rey, and Paul Güssfeldt accomplished a traverse of Mont Blanc, also via the Brenva Spur, showcasing the evolving ambition and skill of mountaineers. Aviation history on the massif was made on February 11, 1914, when Agénor Parmelin became the first to fly over, maintaining an altitude of 5,540 meters for fifteen minutes.

The spirit of exploration continued with the first complete ascent of the Innominata ridge by Stephen Lewis Courtauld and Edmund Gifford Oliver, along with guides Henri and Adolphe Rey and Alfred Aufdenblatten on August 19 and 20, 1919. Marguette Bouvier, in February 1929, became the first woman to ski down Mont Blanc, albeit partially, under severe weather conditions, guided by Armand Charlet. The first winter climb of the Major route was achieved by Arturo Ottoz and Toni Gobbi on March 23, 1953.

A significant aerial achievement was recorded on June 23, 1960, when aviator Henri Giraud landed on Mont Blanc’s summit on a mere 30-meter-long “runway.” This feat was echoed on July 1, 1986, by Dominique Jacquet and Jean-Pascal Oron, who parachuted onto the summit after being dropped from 6,100 meters, setting a world record. On August 13, 2003, seven French paragliders landed on the summit, taking advantage of exceptional thermal ascents caused by a heatwave, starting from various points, including Planpraz, Rochebrune at Megève, and Samoëns.

Between 1986 and 1988, a series of speed records were established, with Laurent Smagghe setting an impressive round-trip record from Chamonix to the summit and back. Kilian Jornet further pushed the boundaries on July 11, 2013, with a record ascent and descent time, highlighting the evolution of endurance and speed in mountaineering. Manuel Merillas, on August 12, 2021, achieved a remarkable round-trip from Courmayeur in 6 hours, 35 minutes and 32 seconds, underscoring the continued passion and pursuit of pushing limits on Mont Blanc.

Scientific Pursuits and Challenges on Mont Blanc: From Observatories to Tunnels and Air Disasters

Joseph Vallot: Pioneering Scientific Research at Mont Blanc’s Summit

At the dawn of the 19th century, Joseph Vallot embarked on pioneering scientific exploration at the summit of Mont Blanc. As a botanist, meteorologist, and glaciologist, Vallot sought to conduct comprehensive studies on meteorology, snow accumulation at high altitudes, and the physiology of mountain sickness. To facilitate extended research periods near the summit, he financed the construction of a wooden observatory, one of the first of its kind dedicated to such studies on Mont Blanc. However, Vallot quickly realized that the scientific work was incompatible with the influx of climbers, prompting the construction of the nearby Vallot Refuge for their shelter.

With the assistance of his cousin, engineer Henri Vallot, they initiated the meticulous task of mapping the Mont Blanc massif at a 1:20,000 scale from 1892. This ambitious project built upon earlier altitudinal measurements by figures such as James David Forbes, Alphonse Favre, and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. A significant refinement in Mont Blanc’s altitude to 4,807.20 meters was achieved through triangulation by Henri and Joseph Vallot between 1892 and 1894. The completion of this detailed cartography, a feat achieved with relatively rudimentary means of the time, was finalized posthumously by Charles Vallot, Henri’s son, who also introduced the esteemed Vallot Guide collection to the mountaineering community.

Before his death, Joseph Vallot bequeathed the observatory to A. Dina, who initiated an astronomical observatory project. It was later inherited by the French state and placed under the custodianship of the Paris Observatory. By 1973, the management of both Chamonix observatories was transferred to the CNRS, with the high-altitude observatory subsequently assigned to the Laboratory of Geophysics and Environmental Glaciology (LGGE). Meanwhile, the Chamonix observatory served as a base camp for CNRS researchers.

The current Vallot Refuge, maintained by the French Alpine Club, serves as a survival shelter for climbers in adverse weather. The Vallot Observatory, located slightly lower, is no longer a refuge but is regularly used by scientists from the Institute of Environmental Geosciences for various high-altitude studies, including atmospheric aerosol fallout, ice core drilling at the Col du Dôme, and physiological research.

In March 2013, the observatory was briefly put up for sale before the transaction was cancelled in August 2013 by the Budget Minister, heeding calls from the Alpine Ecosystems Research Centre (CREA) and other stakeholders to preserve its scientific use as stipulated by Joseph Vallot. A subsequent tender considered this scientific servitude, leading to a proposal from the Chamonix municipality and CREA to purchase and dedicate the site to scientific pursuits. In 2016, the Chamonix municipality acquired the observatory, ensuring its continuation as a centre for scientific research on Mont Blanc.

The Quest for a Summit Observatory: The Janssen Observatory Project on Mont Blanc

In the late 19th century, the ambition to establish a scientific presence at the very summit of Mont Blanc led to a remarkable engineering challenge. Pierre Janssen, a distinguished astronomer and director of the Meudon Astrophysical Observatory, envisioned constructing an observatory on the peak to advance astronomical research. In a bold move, Gustave Eiffel, renowned for his engineering prowess, agreed to undertake this project on the condition of finding a rock foundation within 12 meters below the ice cap.

In pursuit of this foundation, Swiss surveyor Imfeld conducted extensive explorations in 1891, drilling two horizontal tunnels, each 23 meters long beneath the summit’s ice, only to conclude that solid ground was elusive. This setback led to the abandonment of Eiffel’s involvement in the project.

Nonetheless, determination prevailed, and by 1893, an observatory had been erected at the pinnacle of Mont Blanc. This period coincided with a severe cold wave, during which the observatory registered a record-breaking low temperature of -43°C, the coldest ever documented on the mountain.

The observatory’s survival against the harsh mountainous environment was ingeniously supported by levers anchored in the ice, which temporarily maintained the structure’s stability. However, by 1906, significant leaning of the building prompted corrective measures through the adjustment of the levers. Despite these efforts, a crevasse began to form beneath the observatory a few years later, leading to its eventual abandonment. The structure’s demise followed shortly after Janssen’s death, with only the tower being salvaged at the last moment. This episode in Mont Blanc’s history reflects the intersection of human ambition with the formidable challenges posed by nature, underscoring the mountain’s enduring allure for scientific exploration and its harsh realities.

Tragic Skies: Fatal Air Disasters on Mont Blanc

Mont Blanc, Europe’s highest peak, has been the tragic site of two devastating air crashes, marking sombre moments in aviation history. In 1950, Air India Flight 245 crashed into the mountain while on its approach to Geneva Airport, resulting in the loss of all 48 people on board.

This catastrophe was followed by another in 1966 when Air India Flight 101, also en route to Geneva, met a similar fate due to a miscalculated descent by the pilots, leading to the deaths of 117 passengers and crew. Among the victims of the latter was Homi J. Bhabha, a prominent nuclear scientist regarded as the architect of India’s nuclear programme. These tragic incidents underscore the inherent dangers of mountainous terrain and serve as a sombre reminder of the perils faced in the early days of commercial aviation.

Mont Blanc Tunnel: Engineering Triumph and Tragedy

The construction of the Mont Blanc tunnel, initiated in 1946, represented a monumental feat of engineering, creating a vital link through the mountain between Chamonix, France, and Courmayeur, Italy. Upon its opening in 1965, the tunnel, stretching 11,611 meters (7.215 miles), became a crucial transalpine route, facilitating vehicle traffic flow between the two nations.

However, the tunnel’s history was marred by tragedy in 1999 when a transport truck ignited a fire that led to the deaths of 39 individuals. This catastrophic event prompted a comprehensive overhaul of the tunnel’s safety protocols. The renovation introduced advanced computerized detection systems, additional security bays, and an escape shaft parallel to the main tunnel, equipped with a dedicated fire station strategically placed at its midpoint. To ensure a clean air supply, ventilation systems were installed in the escape shafts, and those in the security bays were granted live video communication with the control centre, significantly enhancing the capacity for emergency response.

In response to the disaster, new safety measures were implemented, including establishing remote cargo safety inspection sites at Aosta in Italy and Passy-Le Fayet in France. These sites serve a dual purpose: inspecting all trucks before tunnel entry and managing commercial traffic during peak periods, thereby improving overall safety and efficiency. Following these extensive upgrades, the Mont Blanc tunnel was reopened to the public three years after the fire, marking a new chapter in its storied existence as a symbol of resilience and technological advancement in the face of adversity.