George Mallory is a household name in the climbing community for his early, harrowing expeditions on Mount Everest and the lingering possibility that he had summited the mountain shortly before his death on the 1924 attempt.

The ultimate success of that ill-fated summit attempt is doubtful. Still, there is no uncertainty regarding Mallory’s strong character, work ethic, patriotic contributions, and devotion to his friends and family. In this article, we will dive into George Mallory’s life and fate on the upper reaches of Everest.

Who was George Mallory?

George Mallory was a British climber born in 1886 in the village of Mobberly, Cheshire. An intelligent and ambitious young man, he attended Winchester College on a mathematics scholarship at the age of 13.

At Winchester, Mallory fell under the tutelage of climber Graham Irving. Irving, who died in 1969, later stated, “It was just chance that I took out to the Alps in 1904 a boy destined to become so famous on Everest.” Mallory matriculated to Cambridge in 1905, rowing for the University team and making regular trips to the Alps with Irving and others.

After graduating from Cambridge, Mallory began lecturing at the independent day school of Charterhouse, in Surrey. He also continued to progress as a climber, establishing many new routes. In 1913, he established a new route on Pillar Rock in the UK’s Lake District. Now known simply as Mallory’s Route, this 5.9 was likely one of the hardest climbs in the UK – and the world – for several years.

In 1914, Mallory married Ruth Turner, with whom he eventually had three children. Shortly thereafter, he left to serve as a lieutenant in the First World War, where he participated in several bloody battles including the Somme offensive.

Mallory escaped death and returned to lecture at Charterhouse as before. However, he resigned in 1921 to join in the first of three British expeditions to Mount Everest.

George Mallory’s 1921 and 1922 Everest Expeditions

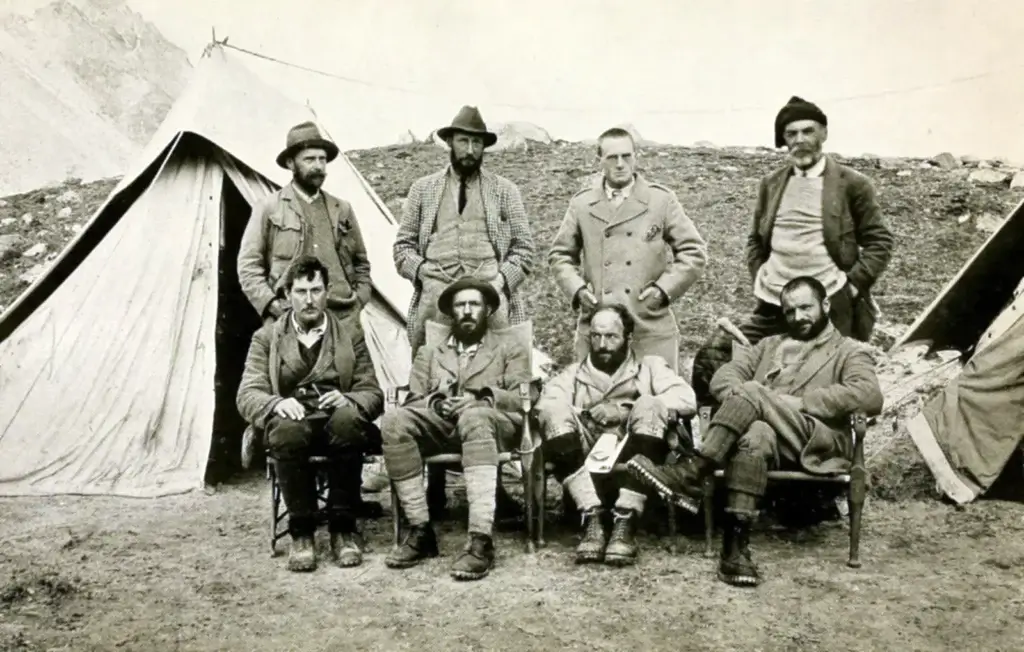

The British expedition in 1921 was led by Colonel Charles Howard-Bury, with celebrated climber Harold Raeburn as lead mountaineer. More a reconnaissance mission than a true summit push, they were the first Westerners to visit the Western Cirque below the Lhotse Face.

Raeburn was nearly 60 years old by this point and was in poor health (he would die just a few years later). Mallory had taken over duties as lead climber, and on September 23rd, the team pushed up to 23,000 feet and spied a viable route to the summit along the Northeast Ridge. The expedition also produced many of the first maps of the Everest region, including the course of the Rongbuk Glacier.

In 1922, Mallory again set out for Everest, this time under the charge of Brigadier General Charles Bruce with Edward Strutt as the climbing leader. The team brought bottled oxygen with them and decided to attempt the summit. An initial attempt without oxygen brought Mallory and two others to a record-setting 26,980 feet on the ridge. A second attempt, this time with oxygen, saw two members of the team reach 27,300 feet before turning back.

The team became increasingly certain they could make the summit. Shortly after, Mallory set out for a third attempt but was soon forced to retreat due to the sudden (but expected) arrival of monsoon season. Disaster struck as Mallory led the team of climbers down a steep slope in fresh, waist-deep snow – the group triggered an avalanche that killed seven Sherpas. The tragedy effectively terminated the expedition. Some members of his team criticized Mallory for his decision-making in the days afterwards. Nevertheless, he remained a respected member of the British mountaineering elite and would go on to make one last attempt at Everest.

The 1924 Expedition And George Mallory’s Death

After his unsuccessful bids for the summit in 1922, Mallory embarked on a tour of the U.S., where he proclaimed that the next British expedition would reach the summit. Mallory believed his age – he was 37 – meant that this would be his last attempt.

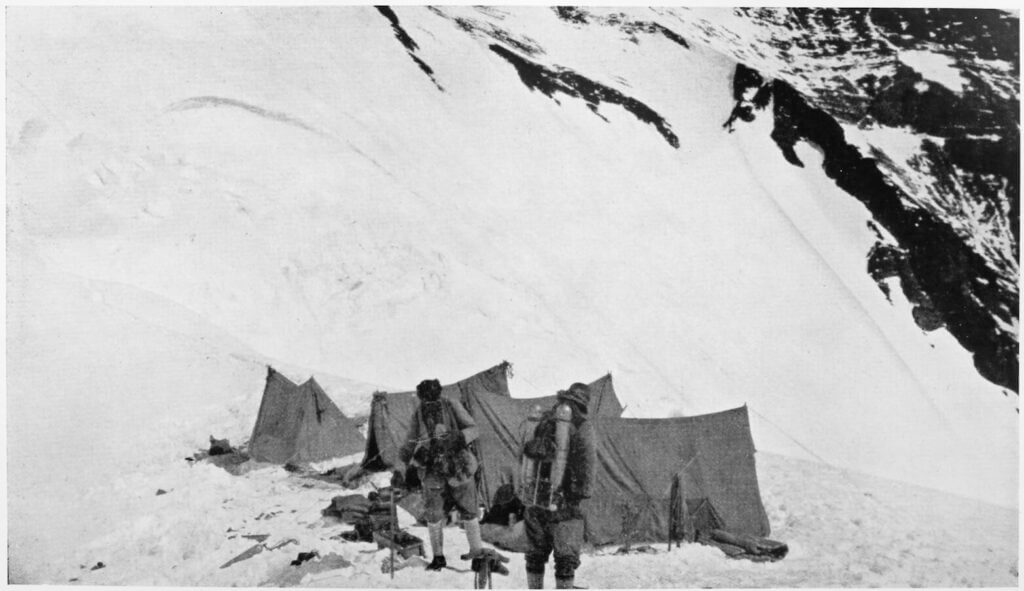

During their first attempt, high winds and extreme cold buffeted the team. They did not advance beyond Camp V. However, a push by Edward Norton and Howard Somervell saw Norton reach 28,126 feet before retreating from exhaustion. This attempt marked a new altitude record less than 1000 feet from the summit.

Ill-fated Summit attempt

The monsoon season was fast approaching, and Mallory knew he had but one remaining chance to achieve his dream. Early on June 8th, George Mallory and partner Andrew “Sandy” Irving set off from Camp IV. Irving, an Oxford graduate and skilled engineer, armed the pair with a custom oxygen apparatus. The team made swift progress up the ridge. Modern calculations estimate that they may have climbed as much as 850 feet/hour during this time.

In the early afternoon of June 8th, teammate and support member Noel Odell spotted the pair climbing over either the first, second, or third step (exactly which of the three remains a mystery) and making fast progress toward the summit:

“At 12.50, just after I had emerged from a state of jubilation at finding the first definite fossils on Everest, there was a sudden clearing of the atmosphere, and the entire summit ridge and final peak of Everest were unveiled. My eyes became fixed on one tiny black spot silhouetted on a small snow-crest beneath a rock step in the ridge; the black spot moved. Another black spot became apparent and moved up the snow to join the other on the crest. The first then approached the great rock step and shortly emerged at the top; the second did likewise. Then the whole fascinating vision vanished, enveloped in cloud once more.”

– Noel Odell

It was an inspiring moment, but it was ultimately the last time either man would be seen alive.

Speculation Surrounding the First Ascent Of Everest

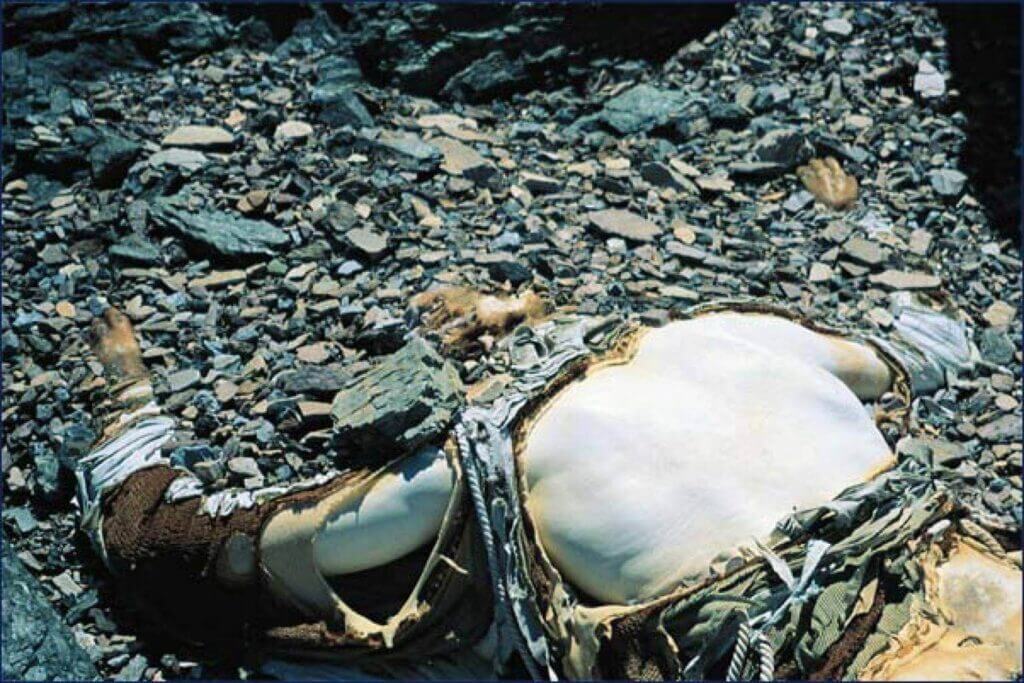

Whether Mallory, Irving, or both men made it to the summit has been subject to intense speculation. Many mountaineers have put in their two cents on what happened, but the best testimony on the subject is probably from Conrad Anker, who led a 1999 expedition to recover Mallory’s body.

Anker believes that it is possible, but improbable, that either man reached the summit before their deaths. The climbing over the second step (later dubbed The Hilary Step) is hard. Climbers say it goes free at about 5.9, which is the limit of Mallory’s climbing at sea level without the extreme conditions and lack of oxygen on the summit pyramid of Everest. For the timetables to make sense, the men would have to have been moving at a very high speed to the summit and back down. No traces of the team were ever found on or near the summit.

Here is a more in-depth discussion of all the evidence available.

Perhaps the whole discussion is fundamentally flawed; Mallory’s son John, who was three years old at the time of his father’s death, has stated, “To me, the only way you achieve a summit is to come back alive. The job is only half done if you don’t get down again.”

George Mallory’s Contribution To Mountaineering

When George Mallory was asked his reason for wanting to climb Everest, he is quoted as answering, “Because it’s there.” This perspective came to dominate the sport of mountaineering.

A list of Mallory’s known accomplishments in climbing includes:

- “Great Gully” (5.6), Cwm Eigeau, Wales.

- “Amphitheatre Buttress” (5.4), Cwm Eigiau, Wales.

- Mont Blanc.

- Mont Maudit. Third ascent via Frontier Ridge.

- “Adam Rib” (5.6) Craig Cwm Du, Wales. First ascent.

- “Mallory’s Route” (5.9), Pillar Rock, Lake District. First ascent.

- 1921 Everest Expedition.

- 1922 Everest Expedition. Summit Attempt.

- 1924 Everest Expedition. Summit Attempt.

Above all, Mallory embodied the archetype of a high-altitude climber. Built like a Greek Titan, he was able to move fluidly and quickly in the mountains, and inspire other climbers in his comfort amidst the vertical world.