Francys Yarbro Distefano-Arsentiev was born on January 18, 1958, in Honolulu, Hawaii, to John Yarbro and Marina Garrett. She grew up in the United States and Switzerland and received her undergraduate degree from the University of Louisville. She later received a Master’s degree from the International School of Business Management in Phoenix.

During the 1980s, she worked as an accountant in the restless ski town of Telluride, Colorado. Francys met legendary Russian climber Sergei Arsentiev in Telluride. The two hit it off and married in 1992.

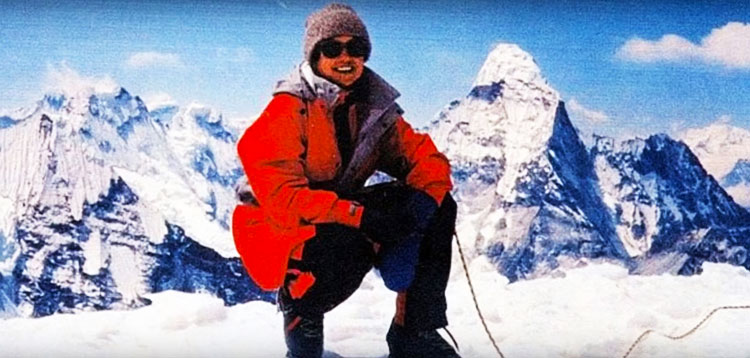

Sergei was already a renowned climber in his native Russia. Known as the ‘Snow Leopard’ among his countryman, he gained notoriety after summitting the five highest peaks in the former Soviet Union. Francys had not been a serious climber when she met Sergei. However, she fed off his encouragement and powerful energy. As a result, Francys found somewhat of a niche pushing the limits on higher and higher peaks with her beloved partner. The couple climbed many Russian peaks, and Arsentiev became the first U.S. woman to ski down Elbrus. Using the West Buttress of Denali as a proving ground, she and Sergei formulated a plan for her to become the first U.S. woman to summit Everest without the use of supplemental oxygen.

Francys was not like most high-altitude climbers attempting to climb Everest outside of a guided setting. By all accounts, she did not possess an obsessive drive like many serious climbers, nor was she a sponsored professional. In the best of times – and with plenty of oxygen – guides can successfully drag their wealthy clients to the summit and down. Nevertheless, even subtle weather changes can spell disaster. When you remove oxygen from the equation, the climb becomes exponentially more serious.

Francys’s 11-year-old son foresaw these risks with more clarity than his mother. As the story goes, Paul Distefano had a nightmare about two climbers who were trapped on a mountain in a storm – the snow seemed to be attacking them. The next morning, he called his mother to tell her about the dream, but she dismissed his concerns and told him she was going on an expedition to climb Mount Everest. Despite his fears, she insisted on going on the trip, telling him, “I have to do this.”

In 1998, Francys and Sergei Arsentiev attempted to climb Mount Everest. On May 17, they reached the North Col, and the following day reached an altitude of 7700 meters. On May 19, they climbed to 8,203 meters and reported they were in good condition and planned to start their summit attempt on May 20 at 1:00 am.

However, their headlamps failed on May 20, and they were unable to continue. They tried again on May 21, but only made it 50-100 meters before turning back.

On May 22, they made a final ascent and reached the summit. The ascent was slow and gruelling, and due to the late hour, they were forced to spend the night above 8,000 meters. By this time, they had been in the ‘Death Zone’ – the area above 8,000m – for over 72 hours without oxygen. As soon as the human body enters this zone, it begins a gradual decline. Cells literally begin to eat away at each other in the struggle for survival.

During the night, they became separated. Sergei returned to camp the next morning, only to find Francys had not yet returned. He once again set off to search for her, carrying much-needed oxygen and medicine. This is the last time other climbers saw him alive. His ice axe was found near her body, but he had disappeared.

The same day – May 23 – an Uzbek team descending the summit came across a body on the route. They found Francys half-conscious and affected by oxygen deprivation, hypothermia, and frostbite. They gave her oxygen and carried her down as far as they could before becoming too fatigued to continue. By this time, Francys was likely hypothermic beyond the scope of the treatment available at base camp. With no other viable option, the Uzbek team laid her to rest and continued their descent. At this altitude it is nearly impossible to carry ones own weight, let alone the dead weight of an incapacitated climber.

Later that day, as climbers Ian Woodall and Cathy O’Dowd attempted the summit, they came across what they initially thought was a frozen body dressed in a purple jacket. Upon closer inspection, they saw that the woman was actually alive and shaking violently. The two climbers approached to help. They realized that the purple-clad climber was Francys Arsentiev, who had previously visited their tent for tea at the base camp. O’Dowd remembered Arsentiev as being a person who “wasn’t an obsessive type of climber” and spoke often about her son and home. Yet, once again, they could provide little assistance so high up on the mountain. Over the next few hours, Francys’s frostbitten dead face lost its color and assumed the pallor of a wax figure, yet she maintained a remarkably peaceful expression. Thus, climbers dubbed Francys the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ of Mount Everest.

Unfortunately, Francys Arsentiev’s dead body remained frozen directly on the main route to the summit. For the next nine years, she became the object of hundreds of photographs showcasing her mysterious resting profile. Her son was subjected to the torture of seeing pictures of his helpless mother’s dead face all over the internet.

Yet, she was only one casualty in a long line of everest bodies that have served as trail markers for decades. Ian Woodall remained haunted by the image of Francys’s dying face all those years ago. In 2007, he organized an expedition to remove Francys Arsentiev’s body from the prying eyes of future climbers. The expedition, known as the ‘Tao of Everest’, succeeded in wrapping the body in an American flag and lowering it down the mountain. Finally out of sight of the main route, Sleeping Beauty forever rests peacefully amongst the clouds.