Rob Hall was a mountaineer from New Zealand, celebrated for his ascents of the Seven Summits in record time, his daring high-altitude escapades, and his successful guiding company ‘Adventure Consultants.’ Unfortunately, he perished in a blizzard with seven other climbers in the 1996 Everest Disaster.

Who Was Rob Hall?

Rob Hall’s Origins

Rob Hall was born on January 14, 1961, in Christchurch, New Zealand. Growing up on the South Island at the foot of the country’s Southern Alps, Hall naturally got into climbing at a young age. By his early teens, he seemingly already had his life mapped out before him. At age 16, he left school early to work as a production manager and designer for a small New Zealand outdoor company called Alp Sports.

Meanwhile, Hall continued to pursue increasingly bold objectives. By the age of 21, he had completed daring routes in the Himalayas, including the second ascent of the North Ridge of Ama Dablam and the second ascent of Nt. Numbur. In New Zealand, Hall completed the first winter ascent of the Caroline Face on Aoraki, the highest Peak in New Zealand.

Strong Climbing Partnership

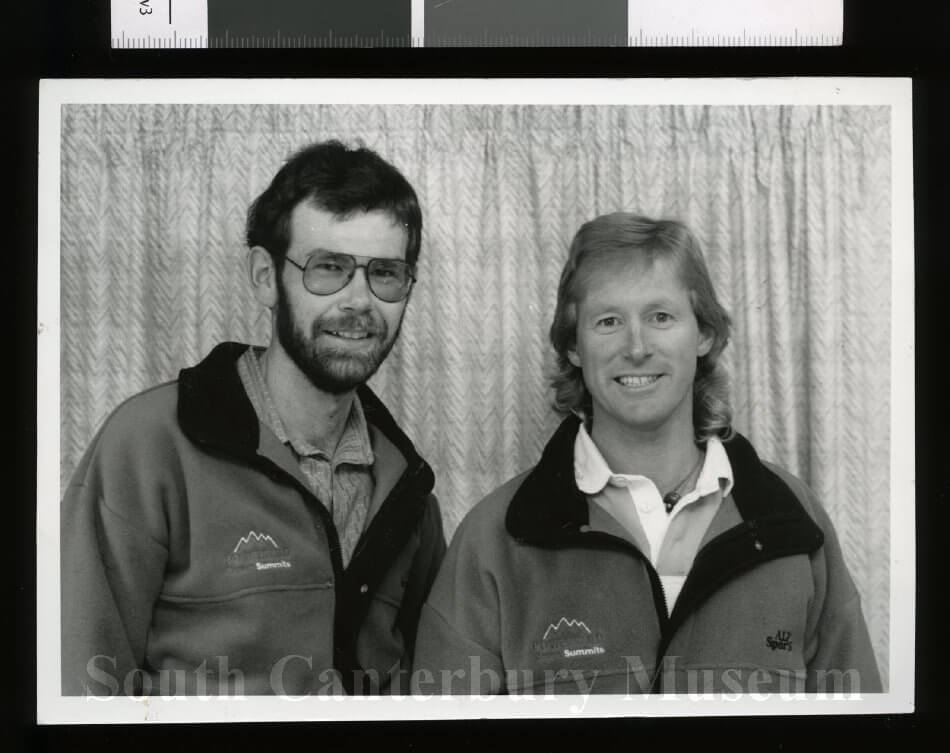

All climbers are familiar with the challenge of finding an equally skilled, trustworthy, and reliable partner with whom to share the adventure of the mountains. One of the great fortunes in Hall’s life was his acquaintance with Gary Ball in 1988. The two quickly formed one of modern history’s most celebrated climbing partnerships.

When the two Kiwis met, the Seven Summits – referring to the highest mountain on all seven continents – had only been completed three years before. Rob Hall and Gary Ball were both drawn to bold and adventurous missions. They were ready to graduate from the Southern Alps of their homeland and take on a challenge that would give them international recognition.

A successful ascent of Everest in 1990 was broadcast live from the summit on New Zealand prime-time television via satellite phone. Seven months later, the two men completed the Seven Summits with their successful ascent of Mount Vinson in Antarctica. A speed record at the time, the completion of this challenge solidified both men in the annals of New Zealand’s climbing mythology.

Rob Hall’s Adventure Consultants

Following the success of the Seven Summits mission in 1990, Hall was flush with accolades and commercial sponsorships. However, he became disillusioned as a sponsored climber and athlete. To maintain rank and influence, he was expected to continue to push the limits in climbing. As an experienced mountaineer, Hall knew he would eventually step over the edge if he kept up this regimen.

In addition to his success as a mountaineer, Hall continued to build a career in the outdoor equipment industry. Following a brief but successful period at Alp Sports, he began work at Macpac Wilderness Ltd, New Zealand’s leading outdoor brand. Four years later, he broke away to start his own company under the label ‘Outside.’ Hall’s career success highlighted his natural ability to plan, organize and execute ideas.

In 1991, Rob Hall and Gary Ball formed ‘Hall and Ball Adventure Consultants.’ The climbers knew that the skills they possessed held value in a burgeoning industry of high-altitude guiding.

Adventure Consultants’ first guiding expedition took place the following year with a successful attempt at Everest. They followed up with trips to Aconcagua and Mount Vinson and returned to Everest in 1993 for another successful shot at the summit. This time, Hall shared the moment with his wife, Jan Arnold as well as some of his clients.

Later that year, Hall and Ball embarked on a personal expedition to Dhaulagiri, the 7th highest peak in the world. The team reached 24,000 ft and was preparing for an assault on the summit when Ball began to show signs of altitude sickness. The group began to descend as quickly as possible, and, despite treatment, Ball perished within 24 hours. Hall lowered his body into a deep crevasse just above base camp and later stated to the press, “Letting go of that rope was one of the most difficult things I’ve ever had to do.”

Hall chose to continue guiding without his partner, shortening the name of the outfit to simply ‘Adventure Consultants.’

Rob Hall’s 1996 Everest Disaster

Overview of the Expedition

By 1996 Rob Hall had led three successful Everest missions and was earning a name for himself within the world of high-altitude guiding. Clients paying $65,000 wanted a return on their investment – they wanted to hire the outfit most likely to reward them with the summit. Hall was that guide.

However, Hall did not have a 100% success rate. Nearing the summit in 1995, he turned his clients back due to excessive snow. The retreat didn’t diminish Hall’s reputation as a guide – it provided evidence of his rational decision-making and competence in the mountains. Hall wasn’t going to put summit ambitions ahead of clients’ safety.

The 1996 expedition consisted of eight clients and three guides, though only five would ultimately attempt the summit. Hall’s clients included three Americans – Jon Krakauer, Doug Hansen, and Beck Weathers. The mission proceeded according to plan for weeks, and only in the last few hours did a series of misfortunes begin to unfold. As a result, May 10-11th became one of the deadliest days in the mountain’s history.

A Series of Delays

The climbers began their summit push early on May 10. Unfortunately, the mission began to derail when Beck Weathers lost visibility due to UV exposure and previous corneal surgery. His snowblindness prompted Hall to move on with the other clients while Weathers waited for their return. Their proximity to the summit meant it should only have been a few hours until the group returned and everybody headed down the mountain.

As Hall’s group continued up the mountain, they discovered that there were no fixed lines. Hall would have to fix the lines himself, costing them more time.

The need to fix lines also produced a bottleneck at the top of the mountain, further dragging out the summit push.

The group continued to labour their way up the mountain, but the extra time cost its members valuable energy. One client, in particular, Doug Hansen, showed signs of dangerous exhaustion as the group neared the summit.

One of the mysteries in the aftermath of the tragedy is why Hall chose to continue to the summit even though the group had missed the 2 p.m. hard deadline to begin descending. Hall himself had established this deadline. He and other guides had learned from experience that it was the absolute latest that a group could start descending and still return to camp before nightfall.

A Storm on Everest

Rob Hall’s group made the summit and began to descend, but by this time, it was well after 3 p.m., and Hansen was showing signs of severe exhaustion.

As if to punish Hall for pushing his luck this far, the mountain became engulfed in a violent snowstorm. Already exhausted, Hansen became unable to continue on. The remaining guides and clients continued down the mountain while Hall stayed with Hansen, unable to abandon his client. Andy Harris, another Adventure Consultants guide, is reported to have joined Hall for a period of time, though his body was never found.

Hansen died a short while later and Rob Hall prepared to bivouac near a col just below the South Summit. He remained in radio contact for 30 more hours. Attempts to rescue him were unsuccessful due to the blizzard conditions. Hall was also insistent on the radio that he would be fine. He did not want others risking their lives to save him.

After more than 30 hours high up on the mountain, Hall grew increasingly scarce on the radio. Eventually, he ceased contact altogether.

Several other tragedies were unfolding at the same time and would increase the body count on Everest:

- Yasuko Namba, the oldest woman to have submitted Everest at the time, died during the descent in the blizzard.

- Three Indian climbers died on the North Ridge on the same night.

- Scott Fisher, lead guide of the Mountain Madness expedition, died during the descent after summitting at 3:45 p.m. He was probably suffering from altitude sickness, further compounded by the blizzard’s effects.

A Tragedy Widely Covered

The tragedy received international coverage due to the reporting from Jon Krakauer, an American journalist on assignment from Outside Magazine. Krakauer went on to write a best-selling account of the incident called Into Thin Air. The book proved to be somewhat contentious in the mountaineering community. Some mountaineers felt that Krakauer, as a mere journalist with no other 8,000m experience, should not have criticized the decisions of experts as much as he did. Others felt that Krakauer offered a fair analysis of the situation. He boldly addressed the ‘expert halo’ often assigned to leaders.

The Fate of Rob Hall’s Body

In 2004, a team of 31 Nepalese Sherpas left Katmandhu on a mission to remove the bodies of four or five climbers as well as a few tons of rubbish. It is nearly impossible for climbers to salvage the bodies of their fallen compatriots during the actual climb. In the death zone above 8,000m, climbers are too fatigued to lower the immobile, frozen bodies of their brethren. The fallen are left where they die and often remain there for eternity. Only half of the 300 bodies on the mountain have been removed.

While some bodies are inaccessible, others are closer to the main route and are easier to transport. “It’s not good to leave dead bodies there. The mountain is also a source of water,” explained Namgyal Sherpa, the expedition leader. Not only are the bodies harrowing for future climbers, but they are also a violation of Nepalese law and customs.

Jan Arnold, Hall’s widow, expressed her wishes for her husband’s body to remain on the mountain. It is “where he’d like to have stayed,” and his body is far from the main route. In fact, it wasn’t even discovered until 1999, three years after the accident. To this day, Hall’s body remains frozen below the South Summit, forever a tribute to that fateful day.