Day 1: entering the Rwenzori Mountains

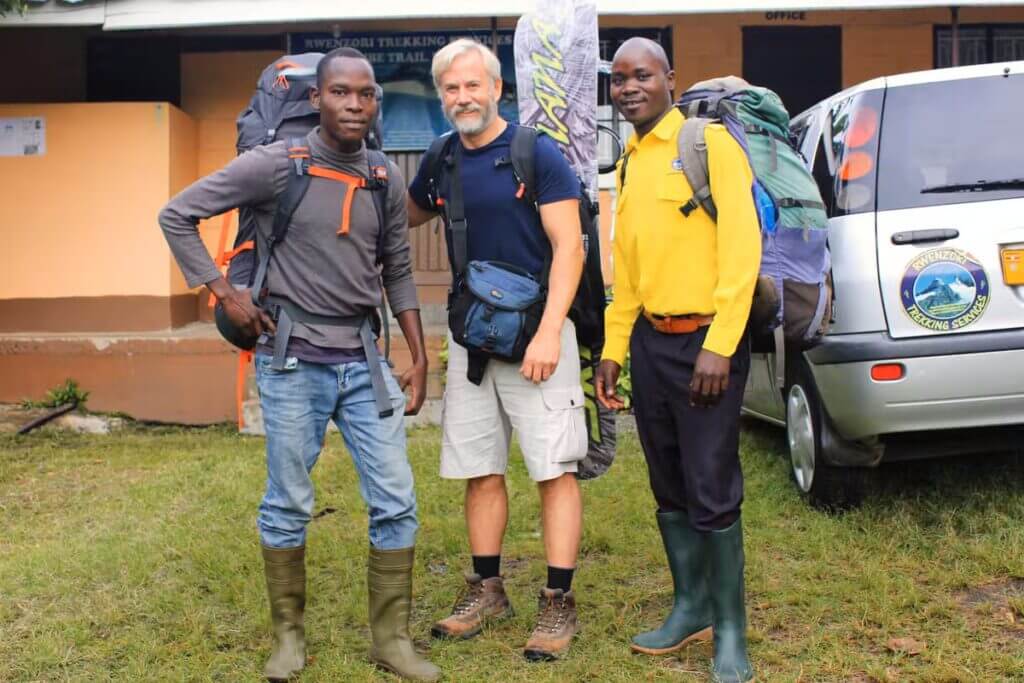

Please meet the team

My climb began from the Trekkers Hostel (@1450m) in Kilembe on April 24th. I was with a guide named Benard and a porter, Vincent, both with Rwenzori Trekking Services. While walking through the village and up to the Rwenzori Mountains National Park ranger post we stopped all along the way to greet the smiling kids and village people. All were asking who is the “Mzungu” (white person) and what was the strange board I was carrying.

Entering the National Park

The park entrance officer gladly received 900,000 Uganda shilling (~$250 USD) from me for the 8-day permit. However, she asked what my board was for since she had never seen one. She asked my guide if it was allowed. This was a tense moment since snowboarding was my primary intent for the trip; I had gone to great trouble to get my board there. I explained that people had used skis on the mountain before and this device for gliding down the glacier should not be treated differently. Fortunately, she seemed to go along with the argument as my guide concurred. The snowboard and I were allowed to proceed. Benard and I made our way up the Kilembe trail with Vincent following. Benard spoke English pretty well, so we had lots of good conversation as we passed through groves of Bamboo and Afro-montane forest with moss and vine-covered trees.

Occasionally we spotted a colobus monkey. We made it to the first hut (Sine @ 2596m) in a little over 5 hours. A second guide, named Edson, also joined up with us for the climb. I washed up at the beautiful Enock’s Falls nearby and took some pictures while waiting for dinner. I decided to go to bed early as I was still trying to catch up on my sleep after 30+ hours of flight from Houston to Entebbe (I don’t sleep on planes well), just a couple of days before.

Unfortunately, I could not sleep until sometime after 3:00 am.

Day 2: to Mutinda, first night in the Rwenzori Mountains

I awoke in the early morning to a pounding at my door and after a tasty breakfast of french pancakes. Edson began to lead me to the next camp (Mutinda @ 3588m). We stopped at the Kalalama camp where we met some Ugandan soldiers who had been returning from training higher on the mountain with French alpine rangers. Apparently, there had been as many as 200 of them on the mountain with only 11 making it to high elevations near the summit. Many had altitude sickness combined with possible hypothermia. I had noticed some along the trail being assisted down.

The soldiers I saw seemed to be ill-prepared and appeared to have just their standard-issue cotton clothing and thin jackets. As we had ascended towards the Kalalama camp and above, the beauty of the Rwenzori Mountains become more and more apparent. We had gone through bamboo forests, by small waterfalls and bright green moss-covered rocks, tangles of bearded heather trunks, and into the mist with hillsides layered with various shades of green and silhouettes of giant heather trees reaching into the heavens.

Day 3: to Bugata camp

The night at the Mutinda camp went poorly for me with regards to getting sleep.

Ugandan soldiers in adjacent huts chronically coughed through the night with loud explosive heaves, possibly to try and clear water from their lungs which I figured was accumulating from either pulmonary edema associated with altitude sickness and/or lung infections from their long exposure to the cold. Fortunately, they headed down as morning came with some individuals being assisted by soldiers on each side.

The guides and I continued upward towards the Bugata camp (4062m). This was a boggy trail day mixed with beautiful scenery, waterfalls, giant lobelias, and a lot of interesting geology. I’m a geologist by profession and was very interested in the rift margin stratigraphy and structure I was seeing in the hills on the west side of the trail. At lunch, I took a brief excursion to some outcrops to take a better look at the outcrops.

We arrived at the Bugata camp around 4.00 pm. At dusk, there was an amazing sky over the Rwenzori Mountains as the waning sunlight painted the rocks and clouds above the mountain ridge an array of eerie colours. A view I will never forget.

Day 4 and 5: acclimatization in the Rwenzori Mountains

The next day was an acclimatization climb up to 4450 m through the Bamwanjara Pass and then down to the Hunwick camp at 3974m.

I also had my first glimpse of a patch of snow or a small glacier on Mt. Baker which stoked my hope of snowboarding! Subsequently, on our 5th day of climbing, we hiked up to the 4495 m Margherita camp and planned for an early 3:00 am departure to reach the summit and allow time for me to snowboard.

There had been a slight rain throughout the day so I continued to be hopeful that it would be snowing near the summit.

Day 6: Snowboarding and Summit Day

A bad night’s sleep

The stress of knowing that I needed to get some sleep before our early departure for our summit climb, means I didn’t sleep well. The key to falling asleep for me is to not think about sleeping, but that’s hard for me to do in situations when I really think I need to optimize my rest.

Benard, Edson, and I left camp at 3:00 am and fortunately the rain had stopped. We climbed making our way over slick rocks and steep portions with some fixed ropes and using ascenders. By 5:00 am, we reached the edge of the glacier on the Stanley Plateau. We put crampons on and roped up and made our way across a black cruddy mix of ice and broken snow crust.

Just before dawn around, 6:30 am, we had hiked to where I thought we should be for a snowboard run at a position on the glacier just to the south side of Alexandra Peak (Rwenzori Mountains). I had seen a relatively recent photo (maybe just a year or two old during the same season) of hikers making their way up a long smooth snowfield on the south side of Alexandra Peak and with the Margherita summit on the right.

The right place?

The slope was gentle to moderately steep slopes to the south of Alexandra Peak with Margherita Peak to the right. The powdery-looking snow in the photo looked great for snowboarding. That is where I wanted to be, and I had tried to pick the right time of the season for that opportunity. Unfortunately, as the sun was coming up there was near whiteout conditions, and at my feet was just a thin firm snow crust and patches of cruddy dark ice. It was so different from what I had hoped for or expected. Was I in the right place?

I came to the conclusion that the glacier had sadly changed that much from the time of the photo

After much discussion with the guides about our location and walking around a bit looking for better snow conditions, I came to the conclusion that the glacier had sadly changed that much from the time of the photo. We also discussed summiting first but conditions were not expected to improve. Also, we would need to ditch the board for the summit climb, and the Margherita Peak portion itself would not be rideable anyway. It would also be a lot to expect to have the time and energy left to search out and find a better place for snowboarding and make a significant run after 5 more hours of climbing. I made the decision to go ahead and snowboard as far as I could safely do so from the current position.

The run

Benard walked downslope as far as he could still see me and for Edson to walk down as far below Benard to be able to see him. I would make a run towards both of them and only go as far past as I thought Edson could see me. Edson was going to take some pictures with his camera, and I had given Benard my camera to video the run. I put on my snowboard boots, strapped in, and began my descent towards Benard who I could just barely see in the distance.

As I made my way I noticed the glacier surface did not improve anywhere and existed of slightly carvable crust and patches of black cruddy ice. I continued past Edson until I noticed that the slope was becoming more convex and steepening slightly, so I decided to turn out and stop. The glacier steepened abruptly just before ending at a cliff. I also didn’t want to go any further than Edson could see me. It was a short run. I walked back up. Edson had found out his camera batteries were dead and Benard wasn’t sure he understood the video controls on my camera. I showed Benard again how to operate the video and took off for a second similar run. It turned out that the video did not record.

Fortunately, I did have a GoPro activated on my helmet, but the run was not that interesting in terms of snowboarding. The video I recorded is documentation of the poor snow conditions and the rapidly melting glacier conditions on Mt. Stanley. I am grateful, in any case, that I was able to see and experience first-hand one of the few glaciers left on the continent of Africa before it disappears.

I cached my board alongside the Alexandra glacier next to some rocks. We then started our final climb towards the summit.

A hard climb

We walked through a rocky canyon portion with odd ice formations with one reminding me of a barracuda’s mouth. We reached a steep edge of the Margherita glacier and roped up. The climb was difficult; even with crampons up a steep icy section until we made it into the main axis of the glacier. The main axis of the glacier actually had very good snow; I was a little bummed that I had not chosen that portion to snowboard down, especially after walking up a long clean section having a nice powdery quality to it.

The Alexandra and Margherita peaks briefly came into view. I was filled with emotion and began to think about my son and I recorded a personal message to him using my GoPro. One could see a large ice wall & wind stacked snow formation at the base of Margherita and some crevasses off to the right. I saw Benard, who was leading walk safely past the left side of the crevasse. I followed pretty much in the same tracks.

All of a sudden I felt my body fall

Thanking the rope

All of a sudden I felt my body fall. I managed to catch myself with my arms at my armpits and my right knee was sort of pinned up against my chest against the lip. I planted my ice axe into the snow ahead of me as I yelled for Benard to arrest and he dropped to a sitting position. He then tried to pull me out, but couldn’t. Edson who was roped behind me downslope made his way around wide to my left to come up to Benard’s position. Looking down between my left arm and my chest I saw nothing but black without a view of any bottom or edges.

My guides pulled me out on three as I managed to also lift up somehow and use my pinned right knee as leverage. I quickly scrambled upslope away from the lip. I don’t recall thinking about it much other than I was lucky and glad we were roped. We continued up to the start of the ice and snow wall and began to traverse around a narrow catwalk with a drop-off to the right and a strange-looking ice formation with long icicles on the left. We traversed further to a rocky wall where I needed to use my hands as we carefully climbed up along a crag of rock and snow to another steep section with some fixed lines that were not ideally placed.

To the summit

Benard climbed ahead of me to a perch to be able to belay me as I climbed using the ropes as well as my hands on the rock to where he was. From there we were able to simply scramble to the top about 60m above us. Our small group had reached the summit around 12:30 pm and decided to not spend much time there. We couldn’t see much anyway with the foggy conditions and we had a long way to go to reach the planned Bugata camp at 4062 m.

Together, we were able to quickly rappel down with a top belay the two steep rocky sections and down the steep edge of the Margherita glacier. Then, we unroped and took off our crampons. Through the rocky canyon and to the edge of the Alexandra glacier, we retrieved my snowboard. From there we climbed up onto the glacier, but for some reason, we did not rope back up or put on our crampons. I assumed we did this in the interest of time and based on the fact that we had made it across earlier without the guides seeing any major issues.

Steeper sections to reach the summit

However, as I made my way across the glacier I noticed that our traverse was on a steeper section than we had crossed earlier. I admit I began to have some real concerns about not having my crampons on. My boots slip a time or two. I saw there were more areas of slick cruddy ice than before. The slope to my left steepened convexly such that I thought if I fell I might just keep sliding and then drop off a cliff to sure death. I determined to be very careful. For additional traction, I walked along with a subtle foot-wide offset I saw in the slope which paralleled a dark seam that transversed the glacier.

We all made it safely across. It was almost 7 pm by the time we made it back to our starting 4495 m camp and it was getting dark quickly. We had been climbing (except for my snowboarding) for over 15 hours. Our original plan to was to make it to the Bugata camp so as to not have to go so far the next day, but we decided to stop for the night and depart around 3:00 am to make up the schedule. Thank goodness! I didn’t want to continue to walk for another 3 or 4 hours.

Day 7: back to camp

For some reason the guides overslept and we did not start until almost 7:00 am. I knew this was going to be a long day since we were also going to take a longer new loop route back to the Kiharo camp (3430 m).

That route turned out to have some pretty treacherous sections. We did not get to them until nighttime – over 12 hours later. We were still a long way from our camp. It also rained the whole way. We encountered a steep chasm with very slick rocks. I was having to sit or use all fours to descend with a weak dying-battery headlamp and Edson was having to go ahead of me and point his light back to where my feet needed to be.

It took 3 hours to descend hundreds of meters to reach the valley floor. We did not reach camp until after 10 pm. We had been hiking for 15 hours. I went to bed after just a few bites of dinner.

Day 8: the last day down

Starting with a bad night’s sleep

It rained hard all night pounding the hut roof like a drum. I recall I didn’t get much sleep. By dawn, the rain had fortunately decreased. Edson and I set out for our last day down the ~15 km trail back to Kilembe.

Benard and the porter, Vincent, were going to join up with us later. It was not long before Edson and I came to a stream crossing. The rain from the previous night and day had transformed what was normally a small quiet stream into a torrent. The stream was not safe to cross at the trail path location. Fortunately, we found a place to leap boulder to boulder downstream.

I was beginning to wonder about other streams we would need to cross throughout the day and hoped that they would recede since the rain had lessened, but that did not seem to happen. Inevitably we came upon a much larger one, a raging river actually. Edson and I looked upstream and down and did not see a safe place to cross. Downriver there were steep drops with large boulders and upstream the river was much wider and split into two. We decided to look further upstream just as Benard and Vincent showed up to help. We found a place to try but we had to cross over thick brush and boulders to get there. I checked to make sure there was a safe stretch below us that was free of sweepers, sharp rocks, and drop-offs. The river branched with the first crossing not being too difficult.

Some difficulties

However, the second branch was wider and there was a large gap that would need to be leapt across to get onto the far bank. We also would need to wade across swift portions since there were no exposed rocks or downed trees to use. Benard went first slowly and was able to scout out where there were submerged flat rocks to stand on at shallow enough depth that the current wouldn’t sweep you off your feet. He also managed to leap over the final gap onto the very brushy bank without sliding back into the river. I then worked my way across as Benard pointed out where the rocks were to stand on.

Edson followed close behind me as we both had ends of a blue strap in hand as a safety measure (the only thing like a rope we had with any of us). We both managed to leap safely onto the opposite bank together. Vincent made it across as well. Fortunately, the worst of the stream crossings were over. At this point, I was able to relax and enjoy the hike down as the sun began to come out. Ridge upon ridge of heather trees came into view highlighted with misty shades of blue, grey, and green.

Later, I was sad to find out that my camera didn’t catch any of these images well. There was much condensation within the lens.

The final leg: a childhood memory

I recall as a child I ran downhill after an all-day hike on a mountain with my parents in Colorado. The hike had been too long and perhaps not all that interesting for a kid and I was excited at the thought of getting back to the campground. I was allowed to run ahead and did so as fast as I could.

I remember the feeling of lightness and almost a sense of flight as my body essentially “fell” down the slope while my legs barely or what seemed like magically were keeping up to avoid actually falling.

While descending the last leg of my trek in Uganda, I noticed that the trail was becoming less muddy and the slope more gradual and even. I decided I could run – even in my wet boots and socks. I also very much wanted to go home. As I ran I felt like I was gliding effortlessly by the bamboo trees and jungle. Sunlight broke through the mist with a strobe-like flickering through the canopy. I flew quickening my stride at the times I saw better or gentler sections of trails ahead.

I hollered as I hurdled a downed tree across the trail at full speed. On and on I ran down the mountain joyfully. It was like I was reliving my childhood on that mountain long ago. Finally, I rested and my guides soon caught up with me. I had pretty much caused them to run as well to keep up with me as required. At times I heard their laughter behind me. That said, I don’t know if they enjoyed it as much as I did. I just knew I was happy to be going home.