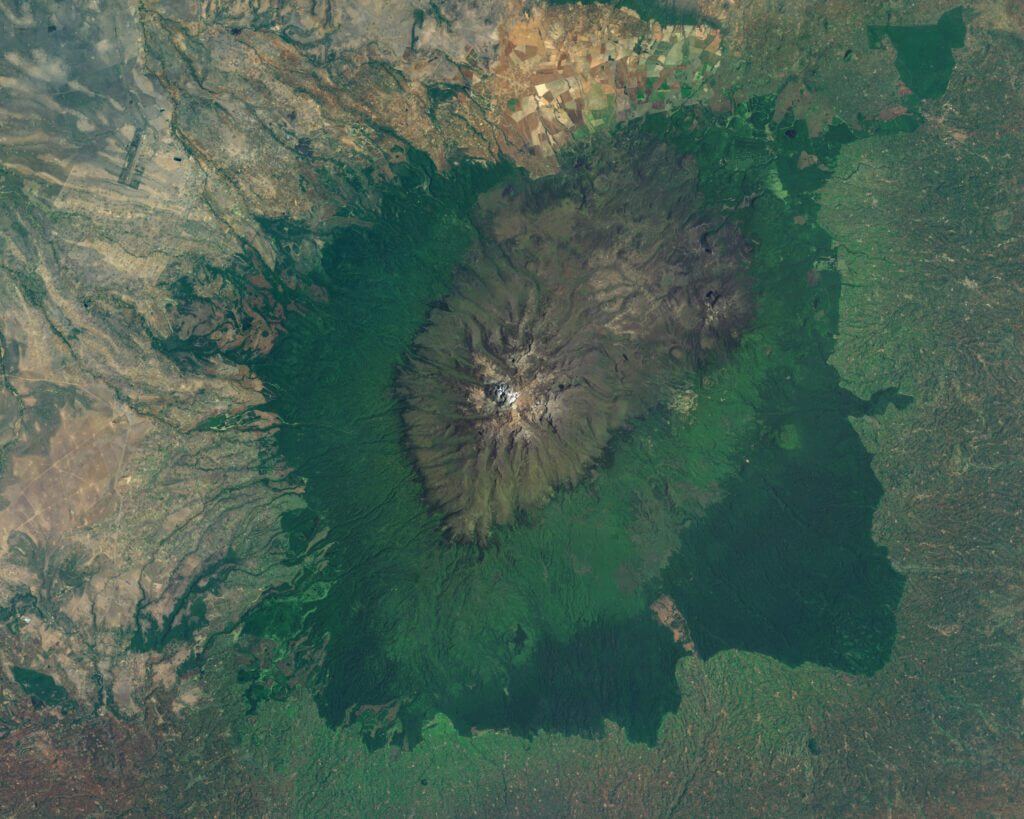

Towering proudly over the Kenyan landscape, Mount Kenya, the country’s highest point and the second tallest peak in Africa, incites admiration amongst the people surrounding it. Majestically rising to the south of the equator, this ancient red volcano is situated approximately 150 kilometres north-northeast of Nairobi, the capital. Its loftiest summits, Batian, Nelion and Lenana, reach respective heights of 5,199 metres, 5,188 metres, and 4,985 metres, offering a sublime spectacle to anyone who has the privilege to behold them.

Mount Kenya, whose name means “mountain of the ostrich” in the language of the Wakamba people who reside at its base, was formed approximately three million years ago as a result of the opening of the East African rift. Its slopes, which were once covered by a vast glacier cap, have gradually been eroded over time by weather and elements, giving it its unique terrain and the numerous valleys that descend from its peak. Today, a dozen small glaciers in rapid retreat bear testament to this glacial past, persisting despite frequently negative temperatures and an extremely variable climate.

Revealed to the European community in 1849 by Johann Ludwig Krapf, the existence of Mount Kenya and its equatorial snow was long a source of scepticism. It wasn’t until 1883 that its presence was officially recognised, and 1899 before the summit was conquered by Halford John Mackinder’s team. Today, Mount Kenya is a favoured destination for climbing enthusiasts, owing to the numerous routes and shelters available for the ascent of its main peaks.

In addition to its topographic splendour, Mount Kenya is also renowned for its biological richness. Eight distinct vegetation zones carpet its slopes, forming a complex ecosystem where numerous species, such as lobelias, senecios, and rock hyraxes, have made homes. To safeguard this biodiversity, a 715 km2 area around the summit has been declared Mount Kenya National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that attracts over 15,000 visitors each year.

Quick Links

- Mount Kenya: A Journey through Toponymy and Etymology

- Exploration of Majestic Mount Kenya Geography

- Geology

- Climate

- The Fascinating Flora and Fauna of Mount Kenya

- At the Heart of History: The Tales and Legends of Mount Kenya

- Populations and Traditions

- Embrace the Adventure: Activities and Experiences at Mount Kenya

- Mount Kenya, listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site

Mount Kenya: A Journey through Toponymy and Etymology

Enriched with a lengthy history and varied traditions, Mount Kenya bears the imprints of local tribes who have interacted with it over the ages. These tribes have attributed various names to the mountain, instilling deep significance and playing a crucial role in shaping the country’s current name.

Indeed, each tribe has its own designation for Mount Kenya. The Kikuyu call it Kirinyaga, meaning the “white mountain” or “shining mountain”, while the Embu opt for Kyrenia, which signifies the “mountain of whiteness”. The Maasai name it Ol Donyo Eibor or Ol Donyo Egere, translating respectively as the “white mountain” and “spotted mountain”. However, the Kamba refer to it as Kiinyaa, meaning the “mountain of the ostrich”, a reference to the contrast of the snow-capped peaks against the black rocks, reminiscent of the male ostrich’s plumage.

The deformation of Kiinyaa into Kegnia, as noted by Johann Ludwig Krapf during his observation of the mountain in 1849, marked the starting point of the evolution of the mountain’s name spelling. At that time, referring to the mountain did not necessitate the addition of ‘Mount’ before its name. The current place name ‘Mount Kenya’ only began to appear in 1894 before being officially recognised in 1920 with the foundation of the Colony and Protectorate of Kenya, previously the British East Africa Protectorate. Later, in 1963, with Kenya’s independence and the election of Jomo Kenyatta as its first president, there ensued a change in the pronunciation of Kenya to ˈkɛnjə, thereby aligning the English and French pronunciations.

The naming of the peaks of Mount Kenya comes from three distinct sources. The peaks Batian are named in honour of the Maasai chief M’batian and his family: Nelion for his brother Nelieng, Sendeyo for his eldest son, and Lenana for his second son and successor. These names were proposed by Halford John Mackinder at the suggestion of Hinde, a resident officer of Maasailand. Other peaks carry the names of famous climbers or explorers such as Eric Shipton, Sommerfelt, Bill Tilman, Dutton and Arthur. Some have been christened after well-known Kenyan personalities, with the exception of the John and Peter points, which were named after two disciples of the missionary Arthur.

Thus, the toponymy and etymology of Mount Kenya reflect not only its natural and geological history but also the cultural heritage of the people who have encountered it throughout the ages.

Exploring the Majestic Geography of Mount Kenya

Mount Kenya: Geographic Majesty and Breathtaking Uniqueness

Majestically rising to an altitude of 5,199 metres, Mount Kenya dominates the landscape at the heart of Kenya, at a distance of approximately 150 kilometres north-northeast of the capital, Nairobi. The giant peak, which marks the highest point in the country and is the second highest summit in Africa, lies just south of the equator. Its rival, Kilimanjaro, is located 320 kilometres further south, on the Tanzanian side of the border.

Surrounded by the towns of Nyeri to the southwest, Nanyuki to the northwest, and Embu to the southeast, Mount Kenya is administratively shared between the counties of Meru, Tharaka-Nithi, Embu, Kirinyaga, and Nyeri. It displays an almost circular volcanic complex stretching over a diameter of 80 to 100 kilometres. A road that runs around its base extends for over 300 kilometres in length.

However, despite its impressive size and influence, Mount Kenya is nearly half as voluminous as Kilimanjaro. This disparity in volume highlights the uniqueness of each mountain, with each peak showcasing its own distinct appearance, character, and magnificence.

The Majestic Peaks of Mount Kenya: Elevation and Volcanic Splendour

Proudly raising their summits to the sky, the peaks of Mount Kenya, predominantly of volcanic origin, present an awe-inspiring spectacle. These mountain formations are concentrated near the heart of the mountain. They exhibit a distinctive alpine appearance, marked by their sharply defined profile and rising at the intersection of the ridges. A little further away, the necks are adorned with a mantle of volcanic ash and earth.

These peaks, each more majestic than the last, reach dizzying altitudes: Batian Peak reaches a height of 5,199 metres, Nelion Peak rises to 5,188 metres, and Lenana Peak comes in at 4,985 metres. The first two summits are separated by an evocative passageway named the “Gate of Mist”. Distinguished from the others because of its location outside the central formation, Coryndon Peak, with its altitude of 4,960 metres, is the fourth highest.

Surrounding these main peaks, other summits such as Pigott Point (4,957 metres), Dutton Point (4,885 metres), John Point (4,883 metres), Lower John Point (4,757 metres), Slade Point (4,750 metres) and Midget Peak (4,700 metres) rise, their pronounced pyramidal shapes offering spectacular relief to the whole. South of the Gorges Valley, a ridge is home to many other high peaks. Further north of the main formation, Terere (4,714 metres) and Sendeyo (4,704 metres) raise their twin peaks, forming a distinctive configuration on the flank of this exceptional mountain.

Hydrography, The Watercourses and Glaciers of Mount Kenya: A Lifeline and its Fragility

The slopes of Mount Kenya are dotted with streams, thus feeding two of the country’s largest rivers: the Tana and the Ewaso Ng’iro. They are of vital importance, providing water to nearly two million people. Each stream is named after the village on the mountainside where it flows. For instance, the Thuchi River marks the border between the Meru and Embu districts. In 1988, the Tana was particularly crucial for the country’s economy, supplying 80% of Kenya’s electricity through a series of seven hydroelectric facilities.

The density of watercourses is notably remarkable on the lower slopes that glaciers have never covered. In the higher parts, the ancient ice cap that covered the mountain during the Pliocene moulded vast glacial valleys, presenting a unique “U” profile, typically centred around a broad river. This is where the shield volcano’s relief was preserved, with the glaciers having carved the mountain’s flanks for thousands of years. Consequently, the mountain’s lower section is characterised by frequent and deep valleys with a “V” profile. The transition between these two types of valleys is distinctly visible.

Many streams from Mount Kenya, such as the Keringa and the Nairobi to the southwest, pour into the Sagana, a tributary of the Tana. Others, like the Mutonga, Nithi, Thuchi, and Nyamindi to the south and east, flow directly downstream into the Tana. The waterways that wind down the northern slope, such as the Burguret, Naro Moru, Nanyuki, Liki or Sirimon rivers, feed into the Ewaso Ng’iro.

At the glacier level, the only hanging glacier on Mount Kenya is situated between the Batian and Nelion peaks, with the remainder being valley or cirque glaciers. Currently, these glaciers are undergoing rapid retreat. Historic photographs, preserved by the Mountain Club of Kenya in Nairobi, demonstrate a significant reduction in the glaciers compared to their state during the first ascent of the mountain in 1899. Regrettably, the total disappearance of the glaciers is projected for the mid-2030s. In 1980, their overall surface area was estimated at 0.7 square kilometres. These glaciers include the Northey, Krapf, Gregory, Lewis, Diamond, Darwin, Forel, Heim, Tyndall, Cesar and Josef.

Geology

Orogeny and Geology: The Volcanic Remnants of Mount Kenya

Mount Kenya is an extinct stratovolcano whose eruptive phase took place between 2.6 and 3.1 million years ago. Its creation is attributed to the opening of the East African Rift, a geological phenomenon which also gave birth to its neighbour, Mount Kilimanjaro. At one point, Mount Kenya likely reached an impressive height of 6,500 metres, boasting a profile similar to that of today’s Kilimanjaro. However, erosion caused by the ice cap has reshaped its structure, reducing its altitude.

Today, the highest peaks of Mount Kenya are the remnants of the most durable volcanic materials. These solidified under the old main crater, forming a crystalline rock known as syenite. This granular plutonic magmatic rock is composed of alkali feldspar, nepheline, biotite and hornblende, which gives it exceptional durability.

The outskirts of the main peaks are scattered with a variety of rock formations. There are found tuffs, conglomerates, and rocks resulting from lava flows, offering a rich and complex geological mosaic that attests to the ancient volcanic activity of this majestic mountain. Thus, Mount Kenya embodies a genuine 3D geological chronicle of East Africa’s orogenesis.

Variety of Soils from Mount Kenya: An Ecosystem Rich in Composition

Mount Kenya is a living canvas of ecological and geological diversity, revealed through the composition of its soils that change from one altitude to another, expressing a complex symphony of natural events.

At the highest altitudes, over 4000 meters, soils are the result of recent glaciations, where organic life is scarce. Here, loams marked by traces of biological life blend with a landscape dominated by scree. Morainic soils and eroded ridges, with more varied forms of organic life, are common beneath these elevations. These soils are fairly young, generally less than 10,000 years, and become finer as they age.

Descending from the altitude of the moors to the bamboo zone, the soils, once covered by the ice cap, are now humic, housing a diverse range of organic life. Intense rainfall caused by the anabatic winds on the western side induces leaching of the soil, leading to the deposit of silt amongst the rocks on the valley slopes. Numerous secondary volcanic vents speckle this area, and the soils covering them sharply contrast with the secondary craters in terms of organic life.

At an altitude ranging between 2000 and 3000 metres, on the lower slopes of the mountain that have never been covered by the ice cap, the forest predominates or alternatively, the land is cultivated. The soil is enriched with a thick layer of clayey humus, although the vegetation on the east and south slopes is less dense, exposing clayey soils. Conversely, the northwest slope harbours well-drained soil of a dark red hue.

At the foot of the mountain, on the foothills, the villages surrounding the mountain feature a dense network of streams flowing into deep valleys, producing brown silt in the centre, near the river beds, and clay on the sides. The soils in this region are generally very fertile, owing to their volcanic origin, and although they are easily erodible, they are protected by vegetation.

Mount Kenya also plays host to periglacial landforms, despite its location on the equator, due to the nocturnal temperatures that encourage the formation of permafrost, located just a few centimetres below the surface. These expansions and contractions on the surface of the soil prevent the establishment of robust vegetation. These diverse types of soils, rich and varied, contribute to the unique character of Mount Kenya and are a vital component of its ecosystem.

Weather

A Seasonal Ball: The Weather Whims of Mount Kenya

Mount Kenya, straddling the equator, boasts a remarkably unique seasonal climate system. With two wet seasons and two dry seasons, it’s a dynamic display of monsoon whims. From mid-March to June, the mountain is swamped by the “long rains” season. Following this deluge, a period of relative drought sets in until September, only interrupted by the “short rains” from October to December. The driest season, which extends from December to mid-March, then brings relief to the saturated lands.

The unique equatorial location of Mount Kenya gives rise to an intriguing phenomenon during the Northern Hemisphere’s summer when the sun is to the north of the mountain. This results in summer conditions on the northern slopes of the upper part of the mountain, whilst the southern slopes experience a pronounced winter. Conversely, during the Southern Hemisphere’s summer, the conditions reverse, creating a fascinating ballet of seasonal climate changes.

These fluctuations between the wet and dry seasons are primarily dictated by the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), a low-pressure belt that encircles the equator. During the two dry seasons, the ITCZ is positioned respectively above the Arabian Peninsula in July and then between the south of Tanzania and the north of Zambia in March. As the ITCZ moves across Kenya between these two extremes, the region enters a wet season.

The volume of rainfall, however, is not constant and largely depends on the surface temperature of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, as well as the El Niño phenomenon. Warmer oceanic waters and a strong El Niño are often the harbingers of abundant rainfall.

The topography of Mount Kenya itself also significantly influences the local climate. Rising steeply from 1,400 metres to 5,199 metres, the mountain faces prevailing southeast winds throughout nearly the entire year, formed by a persistent low pressure above Tibet. However, in January, a reversal occurs, and north-easterly winds sweep across the mountain.

These winds, encountering the formidable obstacle of Mount Kenya during the wet season, bring moisture-laden air from the Indian Ocean. This air, perfectly stratified and cloudy, is generally diverted around the flanks of the mountain to encircle it, especially from June to October eventually. The rest of the year, it is not uncommon for the air to be forced to ascend, causing orographic rainfall, which can sometimes turn into violent storms. Thus, Mount Kenya experiences an endless atmospheric dance shaped by the monsoon, ocean currents and its own majestic stature.

A Celestial Ballet: The Daily Meteorological Variations of Mount Kenya

The daily weather fluctuations of Mount Kenya are marked by a predictable yet spectacular cycle. During the dry season, the African giant experiences wide temperature swings that oscillate between the extremes of day and night, a peculiarity so noteworthy that it inspired Hedberg to coin the phrase, “winter every night and summer every day.” While there may be variations in the minimum and maximum temperatures from one day to the next, the standard deviation of the hourly average remains low, reinforcing the regularity of this weather pattern.

The break of dawn brings a clear and crisp morning with minimal humidity. The direct rays of the sun illuminate the mountain, causing the temperatures to rise swiftly to a peak between nine o’clock and midday, the moment when the pressures generally reach their maximum.

As the day progresses, a noteworthy change occurs at lower altitudes, between 2400 and 3000 metres. The humidity brought by Lake Victoria begins to form clouds over the western forest area. Under the influence of anabatic winds caused by warm rising air, these clouds slowly progress toward the peak in the afternoon. Around three o’clock, ground-level solar radiation is at its least intense, and humidity is at its maximum, which results in an increase in both actual and perceived temperatures. By four o’clock, the pressure reaches a low point.

This daily cloud cover plays a vital protective role for the glaciers on the southwest slope, which without it, would be directly exposed to solar radiation each day, thereby hastening their melt. Continuing their ascent, the clouds eventually reach the dry air currents from the east, giving way to a clear sky from seventeen o’clock onwards and leading to another peak in temperature.

Mount Kenya, situated on the equator, enjoys an almost constant length of day throughout the year, with twelve hours of sunshine. The sun rises at 5:30 am and sets at 5:30 pm, providing an unchanging diurnal rhythm. At night, the sky is usually clear with catabatic winds blowing towards the valleys. Upstream of the low alpine zone, temperatures often drop below freezing, bringing the final touch to this daily ballet of the elements.

A Thermal Spectacle: Temperature Fluctuations on Mount Kenya

The temperatures of Mount Kenya offer a dramatic display of striking variations. On the lower slopes, in the territories, the fluctuation is particularly marked. An average disparity of 11.5 °C is observed over a day at 3,000 meters altitude, 7.5 °C at 4,200 meters and 4 °C at 4,800 meters. With the altitude, the diurnal fluctuation of temperatures decreases, thereby reducing the adiabatic temperature gradient during the day. This signifies that it is weaker than the average for dry air during the day. At night, this gradient is even lower, with katabatic winds from the glaciers causing it to drop further. It is not uncommon for temperatures to fall below -12 °C in the alpine areas. The temperature fluctuation is fewer during the wet season, with clouds acting as a thermal buffer.

The intimate relationship between temperature variations and direct solar radiation is another key element. Direct sunlight quickly heats the ground by a few degrees, which in turn leads to the warming of the air close to the ground. This air cools swiftly to reach equilibrium with the surrounding air when the sky becomes cloudy. Also, the layers of air located fifty centimetres above the ground in valleys transmit heat to the higher layers of air during the night.

During the clear nights of the dry season, the ground cools rapidly, in turn cooling the surrounding air. These thermal exchanges spark the circulation of catabatic winds from the ridges to the valleys, causing a temperature inversion phenomenon. The Teleki Valley, for instance, is often 2°C colder at night than the overhanging ridges, an observation made by Baker. The local flora, such as lobelias or senecios, have had to adapt to these extreme conditions, with the result being that only the largest specimens survive freezing, which is typically lethal for their vital parts.

A Rainfall Paradise: Rains and Snowfall on Mount Kenya

Mount Kenya, which receives abundant rainfall, records its highest volume during the rainy season from mid-March to June, although this level varies significantly from year to year. During the wet seasons, downpours are almost incessant. Nearly half of the annual rainfall falls during the long rains, from mid-March to June, with another third of the total occurring between October and December, during the short rains.

Despite seasonal variations, the southeast slope of the mountain remains the most rain-soaked throughout the year, a consequence of the prevailing wind direction. To the west, the abundance of rainfall is primarily due to the effects of the sun, which, when the sky is clear, drives the anabatic winds into the valleys, guiding the clouds towards the mountain summit in the early afternoon. Without this phenomenon, it has been proven that this area would, in fact, be in the rain shadow.

Beyond an altitude of 4,500 metres, most precipitation transforms into snow. However, due to the dry air that prevails at these heights, snowfalls are rather infrequent. Consequently, the nocturnal freeze constitutes the main source of water in alpine and snowy regions. It plays a paramount role in the nourishment of glaciers, even though there currently exists no accurate way to measure its contribution. Downstream, during the dry season, morning dew fulfils a similar function, and it’s estimated that the majority of small watercourses are fed in this way.

The Fascinating Flora and Fauna of Mount Kenya

The Floral Diversity of the Plains of Mount Kenya

Encompassing Mount Kenya, the plains, or “lowlands”, make up a significant portion of the East African plateau and are generally found at an altitude approaching 1,000 metres. The heat and drought that characterise the climate of these areas have fostered the growth of predominantly savannah vegetation, marked by the presence of thorny plants.

A plethora of herb species thrive here, lending shades of green to this arid landscape. Trees and shrubs, scattered here and there, serve the various needs of the local populations. In these areas, the lantana and various species of euphorbia can frequently be found; these robust bushes are used in the building of hedgerows and palisades.

If the savannahs are home to clusters of original species, dominated by the Acacia and Combretum genera, they have also welcomed new species introduced for nutritional and economic needs. Eucalyptus and fruit trees are among these newcomers that have managed to adapt to this challenging climate, demonstrating nature’s capacity to reinvent itself in response to human challenges and needs.

The Cultivated Lands of Mount Kenya: An Evolving Agrarian Landscape

On the lower slopes of Mount Kenya, at an altitude below 1,800 metres, lies an area of intensive agricultural activity. These regions benefit from a soil enriched with moisture and high fertility due to previous volcanic activity. Once enveloped by lush forests, these lands are now laboriously cultivated, with residual trees serving as a reminder of species that were once present. Some of these trees have been preserved for particular reasons, whether for their sacred nature, as is the case with the fig, or for their practical use. It is not uncommon to see food crops growing in the shade of these silent giants, many of which were spared during deforestation to provide shade for cattle. At the same time, new exotic species such as pine, eucalyptus, and cypress have been introduced.

The impact of Europeans on the agricultural landscape of Mount Kenya is undeniable. Traditional crops such as millet, sorghum and yam, which were cultivated for subsistence during the 19th century, have been supplanted by more lucrative crops such as wheat and barley, favoured by the establishment of large farms.

The variable precipitation levels across the slopes have led to a diversity of crops. On the more humid southern inclines, tea, coffee and rice thrive. The drier northern slopes are favoured for potatoes, corn, citrus fruits and mangoes. To boost productivity, an irrigation system has been established. However, despite the significance of Mount Kenya as a water source, a decrease in the water quantity has been observed in the downstream regions, leading to periods of drought.

The plains of Mount Kenya were once the playground of numerous wild animals. Buffalos, rhinoceroses, lions and a variety of antelopes were commonly sighted, as were hippos and crocodiles inhabiting the rivers. Post-1900, most of these animals were either eradicated or migrated elsewhere, although some, such as hyenas and porcupines, still persist.

While ascending to an altitude of 1,800 to 2,500 meters, a forest of the hill stage is encountered. These forests are exploited by the locals for forestry industries, such as sawmilling, cabinetmaking, and construction. The least productive slopes of Mount Kenya are reserved for livestock farming, primarily for the production of milk.

The Montane Forest of Mount Kenya: A Fragile Ecosystem Abundant in Biodiversity

The landscape at Mount Kenya is characterised by remarkable floristic and faunistic diversity, which varies dramatically with altitude. The outer edge of the forests surrounding the massif starts at around 20 to 25 miles from the centre, where the glaciers are found, and extends for about 16 miles in thickness. The lower altitude of these forests ranges between 2,000 and 2,500 metres. The montane forest that requires at least 1,300 millimetres of rainfall per year primarily grows in the wettest areas. Like the northern slope, the drier slopes are covered with moorland and heather, as inadequate rainfall does not allow for forest development.

The local inhabitants have utilised these forests for centuries, with the harvesting of honey, timber, ivory, animal hides, and certain plants for their medicinal and presumed magical properties, being common practices. However, with the advent of European settlers in the 1890s, the forest underwent radical changes. New exotic plants were introduced, and the fertile soils of the lower slopes of Mount Kenya were appropriated for agriculture, leading to increased deforestation.

Forests are divided into two distinct zones based on the dominant tree species. In the south and east, one will find the humid forest dominated by Ocotea usambarensis, a species closely related to the camphor tree. The north and west are covered by juniper forests, with a small portion of forest extending northeast to the plains of Meru. These forests are threatened by fires which are often caused by the Maasai, who burn the grass to encourage the growth of new shoots after the rains.

On the southern and eastern slopes of Mount Kenya, the “African camphor” (Ocotea usambarensis) forest was extensively deforested by the Kikuyu for agriculture until the establishment of the Forest Administration Staff. The latter educated the Kikuyu about the importance of forest conservation to ensure their survival and sustainable use. The most common tree in this forest is the Mazaiti, which provides excellent hardwood and serves as a sanctuary for bees.

To the northeast of Mount Kenya, the forest on the heights of Meru is distinct for its slightly different species, some of which are now confined to this region due to deforestation. Mammals, such as monkeys, antelopes, rock hyraxes, porcupines, elephants, and African buffalos, coexist in these woods, although the rhinoceros has been hunted to extinction.

The forests of Mount Kenya comprise a rich and diverse ecosystem, albeit fragile. Despite the challenges posed by human exploitation and deforestation, they remain a haven for life and biodiversity, playing a pivotal role in the region’s ecological balance.

The Bamboo Zone of Mount Kenya: An Enchanted Ecosystem of Greenery and Life

The bamboo zone of Mount Kenya is a distinct altitudinal band, stretching between 2,200 and 3,200 metres. Like a natural crown, it encircles the mountain, providing a remarkable and unique spectacle in East Africa. This feature is authentically natural and cannot be attributed to deforestation activities.

Bamboo, specifically Yushania Alpina, is the dominant species in this area. Its growth is closely tied to the environmental conditions, requiring adequate rainfall, gentle terrain and fertile soil. Consequently, the density of these bamboos varies across regions: sparse in the north where conditions are less favourable and absent in some places, while in the west and on the moist slopes of the southeast, these bamboos can grow to dizzying heights, respectively exceeding nine and fifteen metres.

The invasive nature of Yushania alpina significantly impacts the plant diversity in this area. The bamboo suppresses all other vegetation forms, hindering young trees’ growth. Nevertheless, a few large trees scattered about survive, remnants from a past when the vegetation was less dense.

In terms of wildlife, the bamboo region provides a relatively poor habitat. The woody stems of the bamboo are scantily attractive to most animals, resulting in a sparse variety of fauna. However, evidence of animal activity can be seen through the numerous trails crisscrossing the area. These paths are utilised by large mammals such as buffaloes and elephants during their migration between the forest and moorland. Occasionally, these giants of African wildlife indulge in a rare feast of young bamboo shoots.

The Subalpine Floor of Mount Kenya: A Floral Eden between Peaks and Valleys

Perched between 3,000 and 3,500 meters above sea level, the subalpine section of Mount Kenya unveils itself. This expanse, which descends to lower altitudes on arid slopes, is frequently dubbed the Hagenia-Hypericum zone, named after the modest trees that predominate there.

A wind of diversity blows over this kingdom of peaks, where species such as Kniphofia, imposing Lobelia and delicate African violets coexist in harmony. These latter, in particular, add a touch of colour and gentleness to the stark and wild atmosphere of this altitude. This idyllic scene portrays an ecosystem that continues to captivate those who love the mountains and wild nature.

The Moorland and Scrubland Zone of Mount Kenya: An Ecosystem of Contrasts and Diversity

Between 3,200 and 3,800 metres in altitude, the heath and scrubland region of Mount Kenya unveils unsuspected biodiversity, although it is less distinct than its counterparts on Kilimanjaro and the Rwenzori range. This region extends primarily on the eastern slope of Mount Kenya, benefiting from higher rainfall. In the valleys where it dominates, the terrain is often saturated with water, a fact attributable to the relative flatness and poor drainage of these environments. It is in this context that the famous “vertical bog” or “Vertical Bog”, a section of the Naro Moru route which ascends from the upper edge of the forest up to approximately 3,600 metres in altitude, stretches out.

On this damp terrain, the moors grandly unfold, primarily populated by shrubs and tree-like heath (Erica arborea) that can reach ten metres in height. The soil, meanwhile, is adorned with mosses, particularly sphagnum, sedge and rush (Juncus sp.) near bodies of water. All kinds of grasses abound on this marshy soil, interspersed with colourful flowers such as Geranium vagans, Kniphofia thomsonii, Disa stairsii, Gladiolus watsonioides, and Dichrocephala chrysanthemifolia var. alpina. Lobelia deckenii subsp. keniensis can also be found in wet areas, as well as gentians and other alpine species at the highest altitudes.

In the drier environments, the shrubland, or chaparral, prevails, sheltering a more aromatic flora dominated by Artemisia afra or Protea caffra subsp. kilimandscharica. These more drained areas, such as moraines and ridges, are more suitable for this type of vegetation.

As for the fauna, it is represented by the Mabuya varia, a common reptile that conceals itself among tufts of fescue and under rocks. Generally, the animals that inhabit this environment are a blend of forest and alpine species, including rats, mice, and voles, along with their natural predators such as eagles, hawks, and kites. Herds of elands are sometimes spotted, and even lions, albeit very seldom.

The Afro-Alpine Tier of Mount Kenya: A World of Unspoilt Beauty and Exceptional Adaptation

The Afro-Alpine tier of Mount Kenya, a starkly beautiful and isolated world, stretches between altitudes of 3,800 and 4,500 meters. Its unique geographical characteristics have facilitated the evolution of numerous endemic species, populating a landscape shaped by marked temperature variations and a dry and thin atmosphere.

This diverse terrain serves as the backdrop to a kaleidoscope of hardy plants; all adapted to withstand harsh environments. Fescue grasses dominate the scene, but a great variety of wildflowers, featuring more than a hundred species, burst into splendour all year round. Among these are everlastings, buttercups, Asteraceae, and Gladiolus crassifolius, an African gladiolus. The everlastings favour dry areas and produce white or pink flowers, while the yellow buttercups flourish in the moist regions.

However, the true stars of the Afro-Alpine floor are the giant groundsel, unique to the mountains of East Africa. The species Dendrosenecio keniodendron and Dendrosenecio keniensis proudly stand over ten metres tall. These plants, along with Lobelia deckenii subsp. keniensis, have adapted their tissues to allow for the freezing of water within their cells without causing damage.

The fauna of the Afro-alpine zone is as diverse and unique as its flora. The Cape hyrax, the Otomys orestes, and the Grimm’s duiker are the most prevalent mammal species, each having evolved to occupy a distinct ecological niche. Other inhabitants include the omnivorous Lophuromys aquilus and the Tachyoryctes rex, which burrows and feeds on roots and tubers. Predators such as the leopard, the African-painted dog, the lion, and the red mongoose have been observed, but they generally only make occasional incursions into the Afro-alpine zone, preferring the lower regions for their rest periods.

The altitude does not deter a diverse population of birds from making the Afro-Alpine stage their home, with species of sunbirds, Afro-Alpine wheatears, starlings, wagtails, and birds of prey. The black kite, the bearded vulture, or Verreaux’s eagle are just a few of the feathered inhabitants of these high plateaus.

Despite the harshness of the climate, butterflies are present during the dry season. On the other hand, the high altitude is inhospitable for bees, wasps, fleas, and mosquitoes. Aquatic life is also represented by trout, introduced to the streams and small lakes. Moreover, the subalpine frog, alpine lizard, Hind viper, and Algyroides alleni are some of the reptiles and amphibians that reside at this high altitude.

In this landscape of rugged beauty, life has found a way to adapt and thrive, providing an unparalleled mountain experience for explorers in search of exceptional high-altitude scenery. The courageous visitors who journey to the Afro-Alpine tier of Mount Kenya are rewarded with the sight of this living tableau, a celebration of nature’s resilience in the face of extreme conditions.

The Nival Zone of Mount Kenya: A Sanctuary of Life in a Frigid and Delicate Landscape

The nival zone of Mount Kenya typically extends beyond 4,500 metres above sea level, constituting the area from which glaciers have recently retreated. This is a rugged and fragmented terrain, reflecting the disorganised flow of the once ubiquitous glaciers. Only two major glaciers remain; their significant retreat offers an opportunity to study this unique ecosystem.

This austere environment is the cradle of small plant colonies which, despite challenging conditions, have taken root in the land cleared by ice. They grow sheltered from the cold winds that blow from the glaciers and evolve at an extremely slow pace. The most common plants are grasses and thistles, such as Dipsacus pinnatifidus, and, more surprisingly, flowers, including Helichrysum brownei. The latter has been observed at the summit of Batian, one of the highest peaks of Mount Kenya.

The Lewis and Tyndall glaciers, sheltered from icy winds, provide favourable conditions for plant growth. The diminutive Senecio keniophytum flower is the first to colonise these regions, growing nestled amongst the rocks. This adaptive plant, equipped with long hairs to guard against the cold, is followed by mosses and lichens that find a suitable habitat on the moraines. These, by stabilising the soil, promote the subsequent establishment of other plant species.

The Mount Kenya hyrax dwells up to the lower limit of the snow line, typically below 4,700 metres altitude. Although lions and leopards have been spotted at that height, it is an exceptional occurrence.

The avifauna of the nival zone is equally astounding. The Johnston’s Sunbird (Nectarinia johnstoni) thrives even within the outskirts of this area, particularly where the Protea has taken root. The African Rock Pipit (Pinarochroa sordida) also makes its presence known. Above an elevation of 4,900 metres, the African White-bellied Swift (Tachymarptis melba africanus) finds its habitat. This resident bird lives in groups of over thirty individuals and feeds on insects caught along the water’s edge of rivers and lakes.

Thus, despite a seemingly harsh environment, the nival zone of Mount Kenya is home to an astonishing array of life, adapting and thriving as the glaciers retreat. It is a setting that showcases nature’s extraordinary ability to colonise the most unexpected and challenging terrains.

At the Heart of History: The Tales and Legends of Mount Kenya

Saga of Settlement: The Tribal Mosaic of Mount Kenya

The history of the tribes dwelling around Mount Kenya is rich and intricate, and it is only recently that this chronicle has been documented, signalling a substantial shift in the way traditions were conveyed, transitioning from a purely oral system to a written one with the involvement of Europeans.

The Gumba tribe, consisting of pygmy hunter-gatherers, is acknowledged as being the first to occupy Mount Kenya. Despite their significant initial presence, these early inhabitants eventually faded away, giving way to a diverse wave of immigration.

The first tribe to migrate to the foot of Mount Kenya were the pre-Kamba, the ancestors of today’s Wakamba. They arrived from the south before the close of the thirteenth century, heralding the start of a series of migrations that would transform the human landscape of this mountainous region.

At the dawn of the 14th century, the Tharaka and the pre-Chuka followed the migratory movement and settled in the region. The 15th century then witnessed the arrival of the pre-Kikuyu from the Mbéré region. These latter divided to form two distinct tribes: the Embu and the Kikuyu.

The last significant wave of migration occurred in the 1730s, with the arrival of the pre-Meru, who would subsequently be referred to as Ngaa. Originating from the Indian coast, they permanently settled in the region around the 1750s.

This is how Mount Kenya has seen a gradual and diverse settlement. Each tribe, with its own traditions and ways of life, has contributed to shaping the human history of this mountainous region, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of the surrounding area.

Mount Kenya: Unveiling and Conquest of an African Giant

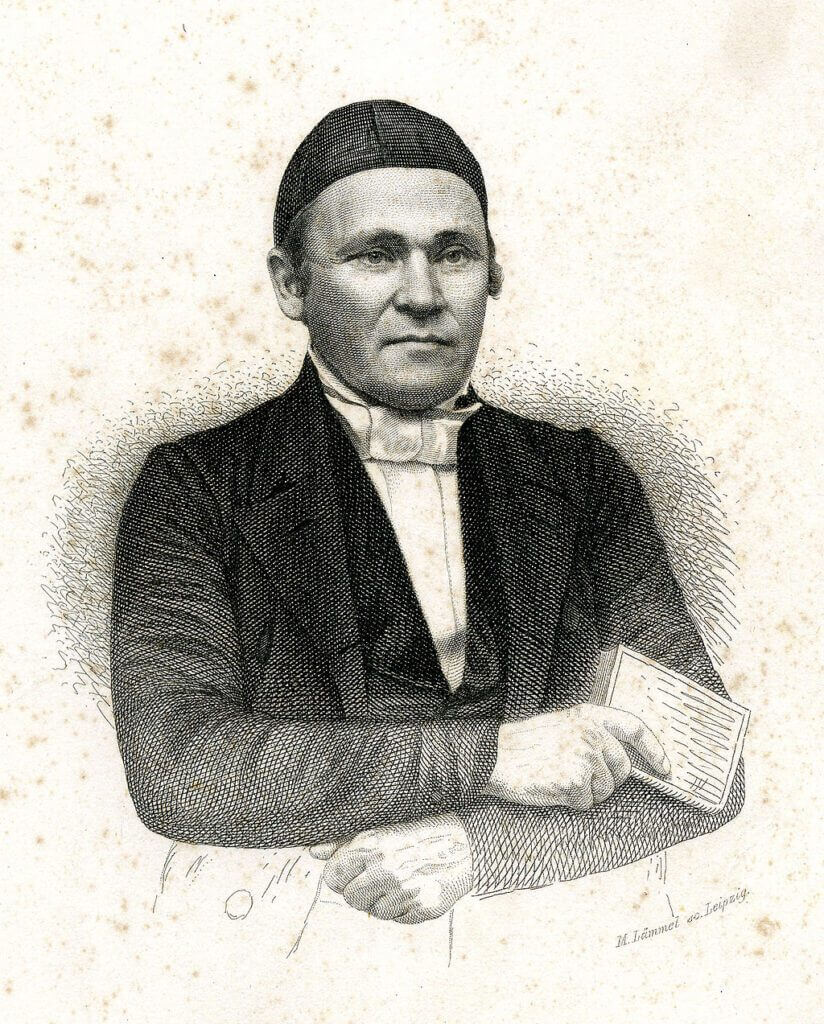

On the African continent, Mount Kenya, with its snow-capped peaks and fertile valleys, is the second of the three major summits to be discovered by the Europeans, following Kilimanjaro and preceding Rwenzori. This discovery is credited to Dr Johann Ludwig Krapf, a German missionary who first sighted Mount Kenya on 3rd December 1849 from Kitui, a town situated 160 kilometres away from the mountain.

The stories of the Embu tribe, who reside near the mountains, describe a landscape struck by intense cold and a “white object” rolling down the slopes with a dull sound. These accounts, along with those of the Kikuyu mentioning a summit covered with a substance resembling white flour, enable Krapf to infer the existence of glaciers on the mountain. This hypothesis is bolstered by the observation that the rivers originating from Mount Kenya and other mountains in the region, unlike traditional rivers of East Africa, never dry up, suggesting a constant high-altitude water source.

Krapf’s discovery of Mount Kenya was initially met with scepticism in Europe, where the existence of snow on Kilimanjaro was still not acknowledged. To support his claims, Krapf compared the situation to the snow-capped peaks found at these latitudes in South America and pointed out that the presence of snow had also been confirmed in Cameroon and Abyssinia (present-day Ethiopia), regions very close to the equator.

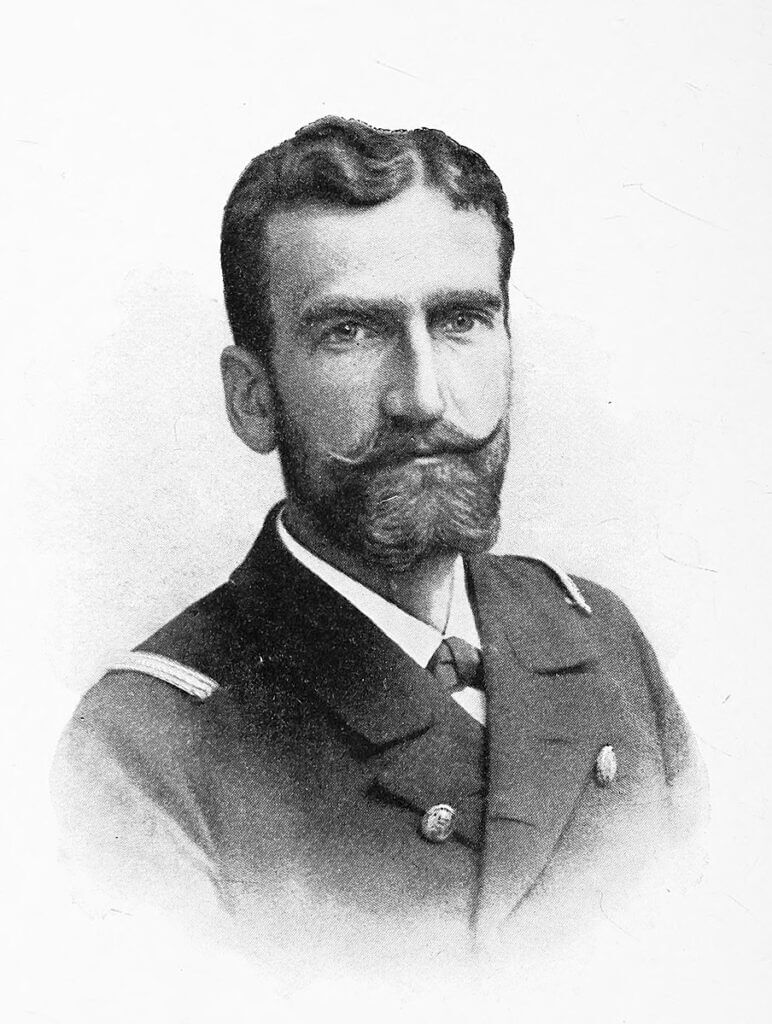

It was only in 1883, thirty-four years after its discovery, that Scottish explorer Joseph Thomson confirmed the existence of Mount Kenya by passing near its western flank. Thomson, who compared its shape to that of Mawenzi at Kilimanjaro, deduced that it was likely the mouth of an extinct volcano.

The first substantial exploration of Mount Kenya was not undertaken until 1887 by the Hungarian Count Sámuel Teleki and the Austrian Ludwig von Höhnel. Despite difficulties and obstacles, they managed to reach an altitude of 4,350 metres on the southwestern slopes. During this expedition, they collected samples of alpine plants from Mount Kenya comparable to those from Kilimanjaro and rock samples, confirming the mountain’s volcanic origin.

In 1893, an expedition led by the British geologist Dr John Walter Gregory, eventually reached the glaciers at an altitude of 4,730 metres. Gregory spent nearly two weeks studying the flora, fauna and geology of Mount Kenya, naming numerous elements to facilitate their description. Regrettably, the expedition was interrupted when the porters, suffering from the cold and altitude, deserted the base camp.

The end of the nineteenth century saw numerous further explorations facilitated by the completion of the railway to Nairobi. Thus, once inaccessible, Mount Kenya becomes a terrain of exploration and study, paving the way for major discoveries about the geology, biology and climate of this iconic African peak.

The first ascent

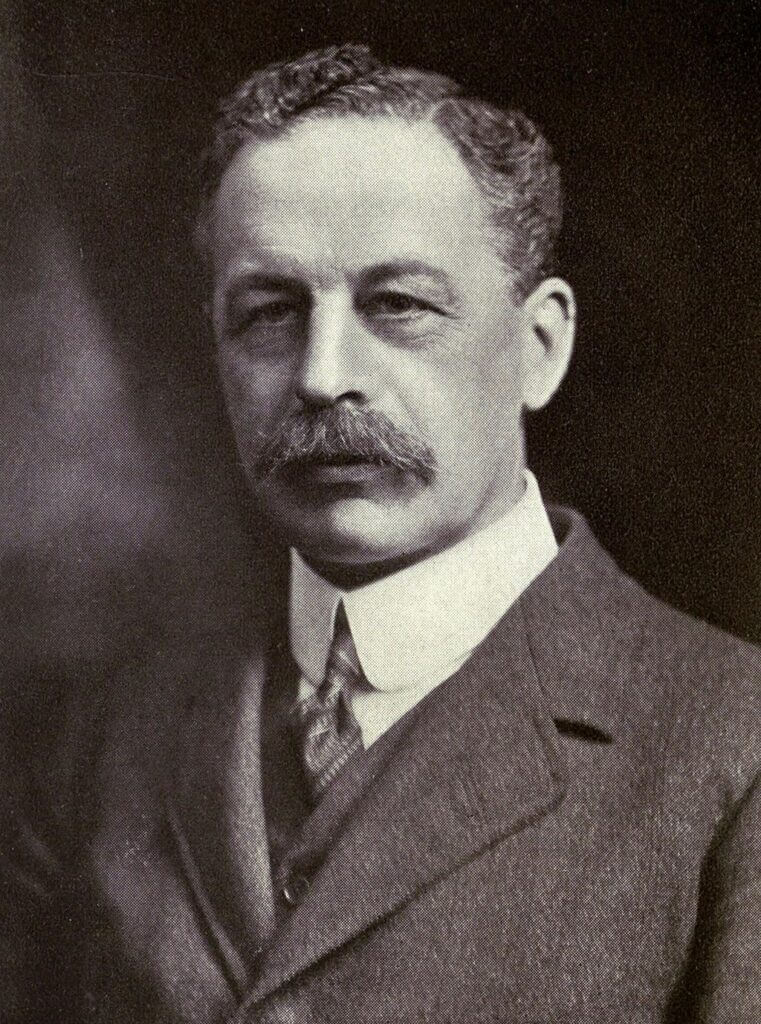

On the 28th of July, 1899, under a deep indigo sky, a diverse company sets off from Nairobi, heading towards Mount Kenya. Sir Halford John Mackinder’s team consists of six Europeans, including two high-mountain guides hailing from Courmayeur, within the Alps, 66 Swahili people, two Maasai guides and 96 Kikuyus.

However, even before reaching the initial slopes of the mountain, the expedition must overcome significant obstacles. The struggle to hire porters in Zanzibar, a smallpox epidemic in Mombasa and then in Nairobi, followed by a hasty departure ahead of mandatory quarantine, leaves the team poorly prepared for the awaiting adventure.

After a three-week trek punctuated by rhinoceros charges, crossings of rivers infested with hippopotamuses, and encounters with local populations of varying degrees of hospitality, they finally arrive at the foot of Mount Kenya. However, at this point, their ability to procure food for the entire team is severely compromised by a recalcitrant local chief, forcing part of the team to set off in search of additional provisions.

Mackinder and his team, despite various challenges, continue their journey. After spending a day in the forest, thanks to the path carved out by Ollier and Brocherel, they arrive in the moorland and set up camp in the Höhnel Valley. This is where their first base camp is established, although their initial expedition to the peaks is nearly catastrophic due to an accidental fire, they ignite.

Their first attempt to ascend Nelion on 30th August concludes with a forced turn-around due to a breach they cannot cross. In the following days, various attempts at exploration and ascent are hampered by insurmountable obstacles and adverse weather conditions.

However, a glimmer of hope emerges on 5th September when the much-awaited rescue team finally arrives with provisions. Mackinder seizes this opportunity to initiate a new attempt to ascend. On 12th September, accompanied by Ollier and Brocherel, they scale the southeast face of Nelion, spend a freezing night near the Gendarme, and painstakingly traverse the Diamond Glacier before reaching the summit of Batian on 13th September at noon.

Despite the peril of afternoon storms, they spend forty minutes at the peak, surveying their surroundings and capturing their triumph with photographs. The return journey via the same route is hazardous but successful.

Before bidding farewell to this majestic mountain, they carry out a final circuit around the main peak zone. They spot Ithanguni, the eastern mountain, before returning to their base camp on 20th September, marking the end of their thirty-three days on Mount Kenya. The journey back to London is undertaken with enthusiasm, eager to share the story of their conquest with the world.

Timeline of the 20th and 21st Centuries

At the start of the 20th century, Mount Kenya, then a British Crown Colony since 1902, saw the establishment of the first major timber company on its northeast slope in 1912. The 1920s witnessed the emergence of plantations, set up to provide fast-growing plant species. Alongside forestry, Mount Kenya was attracting high-altitude enthusiasts. Various expeditions were launched, most of which were undertaken by Kenyan settlers and lacked any scientific aspect.

The Church of Scotland’s Mission in Chogoria plays a significant role in enabling numerous Scottish missionaries to attempt the ascent. New approach routes are plotted through the forest, considerably easing access to the peak region. Ernest Carr contributes to the construction of two shelters, Urumandi and Top Hut, further facilitating mountaineering.

In 1929, the Mountain Club of East Africa was established, marking a significant milestone in mountain exploration. The same year, the first successful ascent of Nelion was achieved by Percy Wyn-Harris and Eric Shipton, who also managed to climb Batian. The latter, accompanied by Bill Tilman, completed the first ascents of many other peaks in 1930.

During the 1930s, explorations took place across the moors surrounding Mount Kenya, well away from the peaks. The year 1932 signified the establishment of the Mount Kenya Forest Reserve. World War II saw a fresh wave of ascents, of which the most notable was achieved by three Italian prisoners of war, as recounted in “No Picnic on Mount Kenya”.

The Mount Kenya National Park was established in 1949, the same year a road was built from Naro Moru to improve access to the moorlands. In the early 1950s, Mount Kenya was the scene of the Mau Mau Uprising, a Kikuyu rebellion against the British Colonial Empire. The following years saw the creation of the Mount Kenya National Park Mountain Rescue Team in the early 1970s and Mount Kenya being designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1978.

The buffer zone, established in 1980 between the forest and agricultural lands, plays a pivotal role in preventing farmers’ encroachment on the mountain. In 1982, the Forest Act was revised, prohibiting the use of the forest for any purpose. Fifteen years later, in 1997, Mount Kenya was finally classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The 21st century is marked by the tragedy of the 2003 air crash, where twelve passengers and two crew members lost their lives. However, the history of Mount Kenya is characterised not only by these dramatic events but also by the intrigue it has held for explorers, climbers and outdoor enthusiasts over the last two centuries.

Populations and Traditions

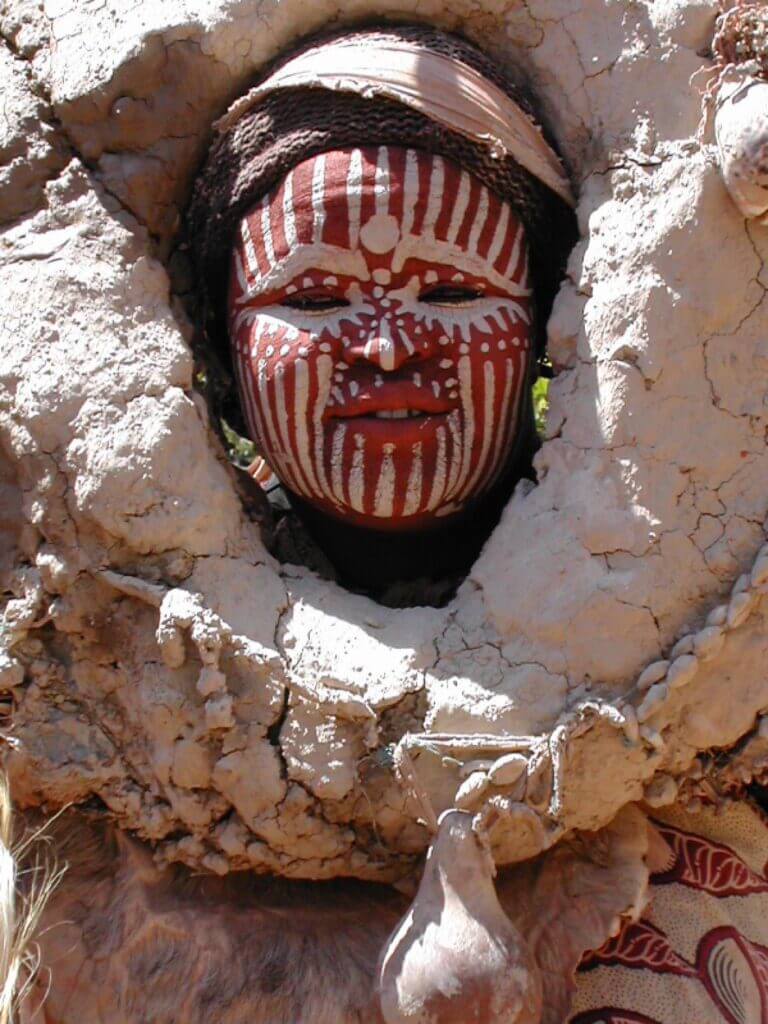

Surrounded by stunning landscapes, Mount Kenya is home to several tribes, including the Kikuyu, Embu, Maasai, and Wakamba. Each of these tribes holds a rich history and traditions that maintain a strong connection with the mountain, which holds profound cultural importance for each of them.

The Kikuyu, for instance, view Mount Kenya as the abode of their supreme deity, Ngai, deeply embedding the mountain within their spirituality and rituals. Similarly, the Embu, Masaï, and Wakamba also have stories and legends pertaining to the mountain, bearing testimony to their ancestral bond with this majestic peak.

In addition to its cultural and spiritual significance, Mount Kenya also represents a source of income for these communities. The flourishing tourist activity, drawn by the striking beauty and the sporting challenges the mountain offers, provides many employment opportunities. Some members of these tribes work as guides, utilising their in-depth knowledge of the terrain and weather conditions to help tourists navigate the mountain safely. Others act as porters, assisting in carrying the necessary equipment for expeditions. Still, others find employment as refuge wardens, hotel employees or within the authorities of the Mount Kenya National Park, thereby contributing to the preservation of the mountain whilst supporting the local tourism industry.

It is also worth mentioning a traditional practice dating back to a time when these communities utilised the mountain as a refuge to evade tax collectors. The relationship between the mountain and the local populations transcends mere economic aspects and unveils the significance of the mountain as a place of safety and sanctuary.

In essence, Mount Kenya is not just a spectacular peak for mountain and outdoor enthusiasts; it also serves as a living space for several tribes whose traditions and lifestyles are intimately connected to the mountain, making it a living tableau of Kenyan culture.

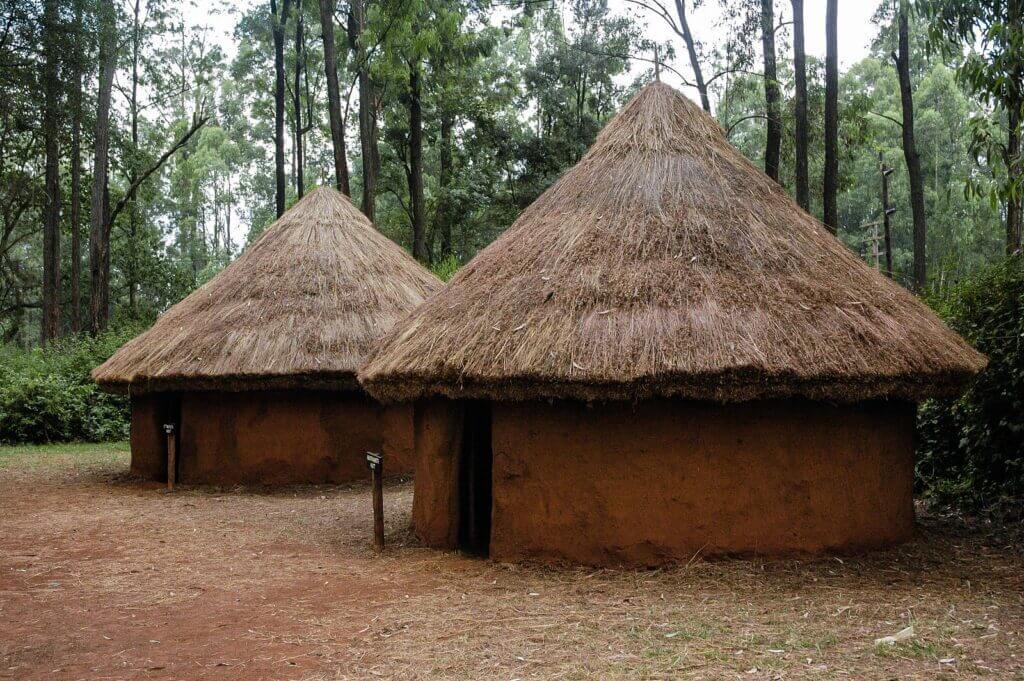

The Kikuyu

Nestled on the southern and eastern slopes of Mount Kenya, in the Kirinyaga district, reside the Kikuyu. This tribe, primarily agricultural, has expertly utilised the fertile lands imbued with volcanic ash from the lower slopes of the mountain, thereby producing diverse and plentiful crops.

The Kikuyu maintain a profound spiritual connection with the mountain, which they refer to as Kirinyaga or Kilinyaga, signifying “The White Mountain”. For them, Mount Kenya is the dwelling of their deity, Ngai. As a continual homage to this divine entity residing at the summit, Kikuyu homes are traditionally built with the door facing the mountain.

The Kikuyu view Mount Kenya as a source of divine inspiration and wisdom. Kikuyu healers frequently undertake pilgrimages to the mountain in search of guidance for finding remedies and therapeutic solutions from Ngai. According to Kikuyu tradition, “When the earth was formed, a man named Mogai created a great mountain called Kere-Nyaga. A white powder known as Ira covered the summit, which was the bed for the god Ngai.”

The mountain also plays a pivotal role during significant tribal ceremonies. Weddings, initiation rites and other noteworthy Kikuyu social events typically take place with the mountain as a backdrop. The majestic presence of Kirinyaga provides a striking setting for these occasions, continuously reminding us of the presence and blessings of the god Ngai.

The Kikuyu exemplify how the local people of Mount Kenya have managed to integrate the mountainous environment into their spiritual beliefs and daily way of life, forging an inseparable bond between man and nature.

The Embu

Living on the southeast side of Mount Kenya, the Embu share similar beliefs and common architectural practices with the Kikuyu, linked with the god Ngai. The Embu term for Mount Kenya is “Kirenia,” translating to “the mountain of whiteness.”

Despite the commanding presence of the mountain in their daily environment, the Embu seldom venture to explore its heights. The low temperatures and rigorous conditions at higher altitudes pose a natural barrier for these tribes. However, this hasn’t deterred them from reaching as far as the Afro-Alpine region of the mountain.

In fact, it was while venturing into these altitudes that the Embu discovered a significant geographical fact about the mountain. They reported to Johann Ludwig Krapf, a European explorer, that the waters of Mount Kenya flow into a vast lake, which then feeds the Tana River. The descriptions given suggest that the only matching lakes would be Lake Michaelson and Lake Ellis, both located in the Afro-alpine zone. This knowledge transfer demonstrates that, despite their reluctance to venture into high altitudes, the Embu have a close and intimate relationship with Mount Kenya, its environment, and its resources.

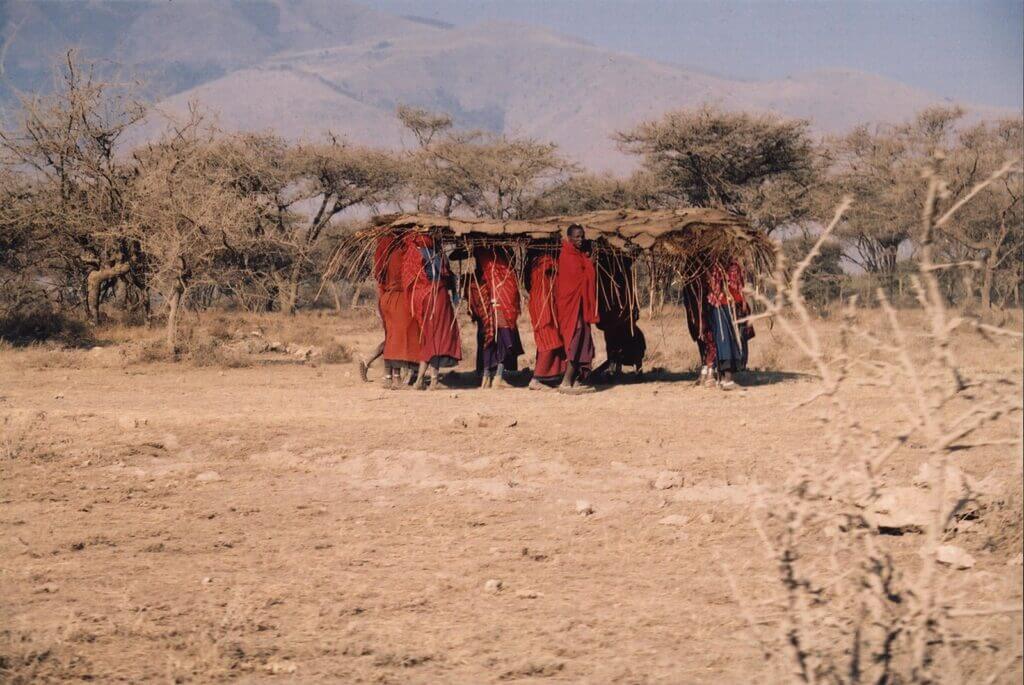

The Maasai

Formerly residing on the north and north-western slopes of Mount Kenya, the Maasai saw their territory diminished by European intrusion. Acknowledged as a nomadic tribe, they used the vast northern regions of the mountain to graze their cattle. However, colonisation pushed them towards reserves further south.

Mount Kenya holds a special place in the ancient beliefs of the Maasai people. According to them, their ancestors first appeared at the dawn of time, descending directly from the mountain. Their affection for this mountain is reflected in the names they give it: “Ol Donyo Eibor” and “Ol Donyo Egere”, which respectively mean “the white mountain” and “the speckled mountain”.

In 1899, when Halford John Mackinder made his first ascent of Mount Kenya, the mountain was regarded by the Maasai as an integral part of their territory. Mackinder believed that the name “Kenya” was a distortion of the Maasai word for “fog”. In tribute to this belief, he named the gap between Batian and Nelion, two peaks of Mount Kenya, as the “Gateway of the Fog”. A suggestive name, highlighting the profound connection between the Maasai and this majestic mountain.

The Wakamba

Situated in the shadow of Mount Kenya, the Wakamba attach symbolism to it, which is as rich as the varied landscape of its slopes. Two names, in particular, stand out: “Kima Ja Kegnia” and “Kiinyaa”, which translate respectively as ‘the mountain of whiteness’ and ‘the mountain of the ostrich’. This latter designation is a direct reference to the striking visual contrast of the peaks, where the eternal snow’s whiteness mixes with the rocks’ deep black, thus reminiscent of the distinctive plumage of the male ostrich.

Other names, such as “Njalo”, are also used by the Wakamba tribe to refer to the mountain. This term, meaning “gleaming”, shares a common root with “Kilima Njaro”, the name of the celebrated Kilimanjaro.

The explorer Johann Ludwig Krapf made the first documented observation of Mount Kenya from a Wakamba village, Kitui, in 1849. Today, it is widely accepted that the modern name “Kenya” originates from the Wakamba term “Kiinyaa”, thus highlighting the enduring influence of this culture on the naming of the entire country.

The other tribes

Ascending above the plains, Mount Kenya is encompassed by a mosaic of tribes, each adding its unique colour to the region’s cultural diversity canvas. The Meru tribe, inhabiting the northeastern slopes, believe that the mountain is the dwelling place of their deity, Ngai. They name the mountain “Kirimaara”, which translates as “the mountain that shines,” likely reflecting the spectacle of the snow-capped peaks glistening under the sun.

The Wakuafi, residing on the southern slope, also refer to Mount Kenya as “Orldoinio eibor”, which translates to “White Mountain”. Meanwhile, the Wadaicho, dwelling on the eastern slope within the forests, sustain a lifestyle centred on nature.

A bit further north, the Wasuk tribe once shared territory with the Maasai. On the western slope, near the base of Mount Kenya, live the Andorobbo, skilled hunters who track buffalo and elephants for sustenance and to sell ivory. They call the mountain “Doinyo Egeri”, which means “black mountain”, a nod to their unique perspective from a slope where rocks prevail and glaciers are less frequent.

Accustomed to exploring or even dwelling in the Afro-Alpine altitude, the Andorobbo nowadays rarely venture beyond the forest. The 1899 expedition of Halford John Mackinder encountered members of the Wanderobo tribe at an altitude of approximately 3,600 metres, testifying to their exceptional adaptability to this environment. Lastly, the Zanzibari name for Mount Kenya is “Meru”, another illustration of the richness of the names and traditions surrounding this giant of nature.

Embrace the Adventure: Activities and Experiences at Mount Kenya

Environmental Protection

The mountain that presides at the heart of Kenya has benefitted from a gradual roll-out of environmental protection throughout the 20th century. As early as 1932, the Mount Kenya Forest Reserve was established, highlighting the importance accorded to the preservation of this exceptional natural landscape. This initial initiative was strengthened in 1942 by the adoption of the Forest Act, aimed at protecting the forested surrounds of the massif.

In 1949, Mount Kenya National Park was established, encompassing the entire area situated above 3,400 metres in altitude and covering a surface of 620 km2. A road was even constructed from Naro Moru, easing access to the moors.

Recognised for its biological and geological richness, Mount Kenya was granted biosphere reserve status by UNESCO in 1978. In 1980, a buffer zone was established to prevent farmland encroachment on the forest, thereby extending the national park’s boundaries up to an altitude of 3,200 metres and expanding its area to 715 km2. This buffer zone was later transformed into tea plantations.

In 1982, the Forest Act was revised to prohibit all forestry operations, ensuring the preservation of the ecosystem. Furthermore, a nature reserve was established, extending the boundaries of the park across 705 km2.

In pursuit of global recognition, the site, which includes the park and nature reserve spanning a total area of 1,420 km2, was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1997. The rationale for this classification emphasises the imposing landscape of East Africa, with its glacier-capped peaks, Afro-Alpine moorlands, and diverse forests, signifying exceptional ecological processes.

A major cleaning operation of rubbish took place in 1998, marking a renewed commitment to the protection of this natural site. Today, the park welcomes more than 15,000 visitors annually, a testament to the importance of tourism for both local and national economies.

The Kenyan government’s decision to designate the region as a national park is underpinned by four main principles: the significance of tourism, the preservation of the site’s natural beauty, biodiversity conservation, and the safeguarding of the area’s water sources for the surrounding regions. This holistic approach ensures the sustainability of this unique natural space.

From Hiking to Mountaineering: Conquering the Heights of Mount Kenya

Majestic Escapade: Exploring the Eight Hiking Routes of Mount Kenya

Mount Kenya, this giant with imposing peaks, offers hikers eight major routes winding towards its summits. These access paths, each unique in their own way, are named: Meru, Chogoria, Kamweti, Naro Moru, Burguret, Sirimon and Timau, to which is added the picturesque circuit of the peaks. Chogoria, Naro Moru and Sirimon stand out from the others due to their popularity. These routes are frequented by a large number of outdoor enthusiasts, making them the most marked routes with defined entry points. The other routes, offering a more wild and isolated experience, require special permission from the Kenya Wildlife Service, thus highlighting their preserved nature and the importance given to the protection of the mountain environment.

Sirimon Route

The journey along the Sirimon Route, acclaimed for its beauty and diversity, begins fifteen kilometres east of the Mount Kenya Ring Road from Nanyuki. The entrance point, nestled ten kilometres further on a footpath or by two-wheel drive vehicles, marks the start of a captivating adventure.

At the outset of this journey, walkers ascend through a dense forest. It is worth noting the absence of bamboo zones on this northern slope of Mount Kenya, a distinct feature that quickly gives way to moorlands dominated by gigantic heather. At the end of this trail, the Old Moses Hut serves as a stopover before the path continues its ascent to the top of the hill.

Here, the path splits into two routes. The left option, though less travelled, offers a scenic crossing along the side of Barrow up to the Liki North Hut. The vegetation here is more sparse, showcasing giant lobelias and senecios.

The trail then ascends along a ridge before joining the main path that rises through the Mackinder Valley. Just before reaching Shipton camp, one can discover Shipton cave, nestled within a rocky outcrop to the left of the escarpment.

From Shipton camp, there are several choices available to hikers. Some may choose to climb directly up the ridge facing the camp towards the old site of the Kami Hut, while others may prefer to follow the river course to Lower Simba Tarn and perhaps even to Simba pass. Each of these places is a stop on the famous circuit of peaks. This adventure takes you through landscapes of exceptional diversity and beauty that forever leave a mark on nature and mountain lovers.

Timau Route

With a somewhat unique nature, the course of the Timau Route presents itself as a limited yet emblematic pathway of the Kenyan mountain range. Beginning in the village of Timau, this journey is closely tied to that of the Sirimon Route. It stands out by circumventing the edge of the forest over a notable distance, thus providing a contrasting immersion into the mountainous ecosystem.

In the past, this path was utilised to travel by vehicle to the highest accessible point of Mount Kenya, thus demonstrating its ease of access compared to other routes. Nevertheless, the Timau Route bears the marks of time and has been neglected through the years, turning its practicability into a sweet memory for former visitors.

From the end of this ancient trail, the adventure is by no means over. In just a few hours’ walk, it is indeed possible to reach the Hall Tarns, a collection of high-altitude lakes with crystal-clear waters. From there, the path continues along the course of the Chogoria Route, leading straight to the circuit of peaks, the cherry on the cake of this exploration of Mount Kenya. Therefore, even if it is less used these days, the Timau Route still has its share of surprises and memorable experiences for those who dare to venture on its paths.

Meru Route

The Meru Route, less conventional, provides a unique experience to hikers. It commences from Katheri, located to the south of Meru, a starting point which stands out from other routes. Instead of aiming directly for the peaks, this route favours a more lateral exploration of Mount Kenya.

Indeed, the trail follows the Kathita Munyi River, a waterway that meanders through the majestic mountain landscape. This route offers a rich and diverse natural spectacle, where the calming sound of the flowing water accompanies walkers throughout their journey.

But the zenith of this route is not a lofty peak, rather, it’s an equally magical place: Rutundu Lake. Nestled in the shadow of towering summits, this crystal-clear lake offers a tranquil and serene scene, almost out of time.

The trails of the Meru Route also traverse the alpine moors that cloak the slopes of the mountain. These landscapes, steeped in a unique and resilient flora, provide a striking natural spectacle that marks the minds of hikers. In summary, the Meru Route, although it does not reach the peaks, promises an authentic and emotionally rich experience at the heart of the splendour of Mount Kenya.

Chogoria Route

The Chogoria Route, a breathtaking journey, begins in Chogoria and leads to the circuit of Mount Kenya’s summits. The initial section, a 32-kilometre trip from the forest entry point to the park, is typically covered by vehicle. Travellers may be astounded by an abundant wildlife population in the forest, with columns of Dorylus ants crossing the road, arboreal monkeys, and potentially even elephants, buffaloes, and leopards. The track, in poor condition, requires a certain degree of caution.

As travellers approach the park, they are greeted by a bamboo area, with specimens growing up to twelve metres high. The path then winds its way through rosewood forests, where lichens dangle from the branches. At a certain point, the route divides into two trails: the smaller one leads towards Mugi Hill and runs along Ellis Lake.

At the end of the trail, a small bridge spans the Nithi stream, and after a few hundred metres, it opens up onto the Gates Waterfall. The path then reaches a ridge overlooking the Gorges Valley, offering a striking panorama of the peaks, Michaelson Lake, the Temple, and Delamere and Macmillan peaks at the other end of the valley. The Hall Tarns, small mountain lakes, are situated to the right of the path, above the Temple, a 300-metre high rock bar overlooking Michaelson Lake.

As the trail continues, it intersects the sources of the Nithi, where the slope suddenly turns steep. It ultimately splits into two, leading west to the Simba pass and southwest to the Square Tarn, both of which are part of the peak circuit.

Kamweti Route

The Kamweti route follows the course of the Nyamindi West River, thus providing a journey into the heart of the mountainous currents. However, this path is not without its challenges and mysteries. Access to it is indeed strictly regulated, adding a shroud of inaccessibility that could attract the most adventurous. Nevertheless, an aura of uncertainty surrounds this route. In fact, Kamweti is no longer mentioned in the official guide published by the Kenya Wildlife Service, calling its very existence into question.

Furthermore, no guarantee of practicality is provided for this trail, adding an additional layer of intrigue to this route. Thus, it presents a challenge for intrepid hikers, ready to discover less trodden and perhaps forgotten paths of Mount Kenya.

Naro Moru Route

The Naro Moru route, highly favoured by hikers eager to reach the Lenana peak, holds distinct appeal. Its ascent, achievable in just three days, along with the presence of dormitories at each camp, absolving hikers from bivouacking, contributes to its popularity. The path typically offers good terrain, with the exception of a section known as “the Vertical Bog”, which poses a particular challenge. Beginning its trajectory at Naro Moru, the route makes its way towards the park headquarters, following the ridge between the Northern and Southern Naro rivers.

At its end, a weather station – accessible by vehicle during the dry season – provides a particular point of interest. From there, the route descends into the Northern Naro Moru valley, down to the Mackinder camp, located on the peak circuit.

Burguret Route

The journey along the Burguret Route, despite being regulated, offers an unforgettable mountain experience. The journey commences in Gathiuru, a place tucked away within the shelter of massive mountains. The route largely follows the winding course of the North Burguret River, a constant companion whose tumultuous waves bring life to the journey. Progressing along the trail, immersing yourself within the region’s lush and rugged landscape, concludes at the Hut Tarn, a strategic point on the peak’s circuit. This journey, juxtaposing natural beauty and physical challenges, provides a true immersion into the beating heart of the mountain.

Peak Circuit Route

The Peak Circuit Path, with its length of roughly ten kilometres and a total elevation gain of over 2000 metres, is a demanding but incredibly rewarding experience. Winding around majestic peaks, this route offers breathtaking views and an unparalleled closeness to the mountain’s contours. While some intrepid walkers choose to complete it in a single day, most prefer to savour it across two or three days. Despite the physical challenge, the route does not require any technical climbing, making this wonder accessible to all duly prepared hikers. Furthermore, the Peak Circuit Path can also serve as a connecting route to join other trails, thus providing endless possibilities for discovering the hidden treasures of the mountain.

Mountaineering – Climbing Mount Kenya: Between Challenge and Wonder

Mount Kenya, the second tallest peak in Africa, standing at a height of 5,199m, has long been overshadowed by the popularity of Kilimanjaro. This mountain exhibits a distinctly different profile, sculpted by the erosion of an ancient volcano, revealing a series of peaks reminiscent of the Alps. It proudly bears a name derived from the Wakamba term meaning “Mountain of the Ostrich”, a reference to its contrasting colouration: effusive black rocks mingling with the white patches of glaciers and snow.

Scaling this peak, which was first conquered in 1899, presents an invigorating yet achievable challenge. The expedition typically lasts between three and four days, but can extend up to a week, depending on the chosen route. There are at least six paths, of which three are more popular, and the number of porters can vary.

The standard route, known as Naro Moru, isn’t necessarily the most picturesque, but nonetheless affords breath-taking views. The initial 20 to 25 kilometres of the approach can be covered on foot or by 4×4 over tracks that often morph into rivers of mud, cutting through dense, humid forest. The scenery gradually transforms into bamboo forests, then bare, steep slopes, scattered with jagged volcanic rocks. Large endemic plant species, such as giant groundsel and swollen lobelias, contribute to the unique landscape.

Beyond Mackinder’s Camp, which one departs before dawn, the high mountain unfolds with sheer and vertical walls, peaks dotted with clouds, corridors, moraines where rock hyraxes live, and finally, the first snows. The glaciers, constantly melting, mostly resemble stumps. However, there is still enough ice and snow to make Mount Kenya the water tower of the country’s centre.

The ascent typically concludes at Lenana peak for novice climbers, peaking at 4,985 metres. Only experienced mountaineers dare venture to the Nelion (5,188 m) and Batian (5,199 m) peaks, additional challenges offered by this unique mountain.

The Shelters of Mount Kenya: A Haven of Comfort in a Demanding Environment

On the slopes of Mount Kenya, various shelters provide basic accommodation and comfort to hikers. These facilities, ranging from the most rudimentary to the most luxurious, are often overseen by on-site managers.

The most basic shelter, Liki North, offers little more than a roof to protect oneself from the elements. At the other end of the spectrum is the Meru Mt Kenya Lodge, offering more luxurious amenities such as a fireplace and running water, a striking contrast to the wild surroundings it is nestled in.

Most shelters on Mount Kenya, despite the lack of heating and lighting, are spacious, featuring dormitories and communal areas where hikers can rest and mingle. These shelters also offer separate lodgings for porters and guides, who play a crucial role in the hiking experience on Mount Kenya.

The common areas of the shelters are not solely reserved for residents. Campers can also utilise them for protection against inclement weather or for storing provisions out of reach from hyenas and Cape hyraxes, curious inhabitants of the mountain. These shelters play a vital role in providing a safe and comfortable space amidst the demanding and at times unpredictable nature of mountain hiking.

Austrian Hut / Top Hut – 4,790 metres

The Austrian Hut / Top Hut refuge, nestled at 4,790 metres on the Mount Kenya peak circuit, sets itself apart with its altitude. It is the second highest refuge on the mountain, surpassed only by the Howell Hut perched atop Nelion. The refuge serves as a strategic starting point for numerous adventures, from ascents of Lenana to the Thomson, Melhuish, and John peaks. For those choosing to embark on exploring the Nelion Normal Route, a stay at the Austrian Hut / Top Hut refuge is a must.

The surrounding landscape of the refuge is remarkably austere yet possesses a peculiar beauty. The ridge where the refuge is located is dotted with lava formations that sketch fantastical silhouettes onto the scenery. Despite the extreme environment limiting fauna – with neither mammals nor birds surviving at this altitude – certain small flowers manage to surprisingly grow amidst these conditions. The ridge is covered with scree that freeze every night and bake in the day, adding to the rusticity of the environment. The Austrian Hut / Top Hut refuge is truly a restful oasis in a landscape shaped by extreme forces.

Two Tarn Hut – 4,490 metres

Nestled along the circuit of Mount Kenya’s peaks, lies the Two Tarn Hut, a refuge situated at an altitude of 4,490 metres. Much like a rare gem, it is located in an austere yet awe-inspiring mountainous environment, providing necessary shelter for hikers and climbers embarking on this picturesque trail.

Meru Mt Kenya Lodge – 3,017 m

Perched at an altitude of 3,017 metres, on the edge of Mount Kenya National Park, Meru Mt Kenya Lodge unfurls its charm on the Chogoria route. Home to several log cabins, this private lodge stands out for its warm and rustic character. Each cabin provides comfortable accommodation, with a bedroom, a kitchen, a bathroom and a living room adorned with a fireplace, thereby creating a cosy atmosphere for weary visitors after a day of hiking.

The carefully considered interior layout can accommodate three to four individuals in each cabin. Luxury is not in short supply within these mountain retreats, where hot running water is a blessing after a long day’s trek in the coolness of the heights. Approximately 500 metres from the park entrance, the lodge requires the payment of national park entrance fees.

The Meru Mt Kenya Lodge, with its log cabins and breathtaking views of the surrounding landscape, provides a true haven of comfort and tranquillity in the wild hinterland of Mount Kenya. This is an ultimate destination for adventure and outdoor enthusiasts who wish to immerse themselves in the stunning beauty of this part of the world, whilst enjoying the conveniences of civilization.

Urumandi Hut – 3,063 metres

At the heart of Mount Kenya, along the Chogoria trail, stands a relic of the past: the Urumandi Hut. Constructed in 1923, this historical refuge bears the marks of almost a century of mountaineering history in Kenya. Its structure, now neglected, appears to blend into the mountainous landscape, a silent witness to the evolution of hiking practices and routes.

Despite its current disuse, the refuge once served as a shelter and rest point for intrepid hikers navigating the Chogoria route. Today, even though it no longer provides respite for weary hikers, its existence remains a tangible relic of the history of mountaineering in this region. The Urumandi Hut, with its solitary silhouette against the mountain’s grandeur, stands as a symbol of the passage of time and the evolution of outdoor adventures on Mount Kenya.

Minto’s Hut – 14,075 ft

Perched at a formidable altitude of 4290 meters and nestled near to the Hall Tarns on the Chogoria route, Minto’s Hut provides sanctuary for eight individuals, typically porters. Nearby, there is a camping area for those who prefer to sleep under the starlit sky.

Water, a vital resource at this altitude, is directly drawn from adjacent mountain lakes. However, due to the lack of an outlet, it stagnates and must be carefully filtered or boiled before consumption.

Warden’s Cottage – 2,400 m

The Warden’s Cottage, once the residence of the park’s veteran wardens until 1998, takes pride of place on the Naro Moru route. Within this charming retreat, one will discover two bedrooms, a bathroom, a kitchen and a living room equipped with a veranda and a fireplace. Running hot water is a welcome luxury in this rustic setting. Due to its location within the park, payment of taxes is required.

The Weather Station – 3,050 m

Under the management of the Naro Moru Lodge, the weather station provides a number of dormitories for tired travellers, as well as a camping area for those wishing to be closer to nature.

Mackinder’s Camp – 4,200 metres

Mackinder’s Camp, another retreat managed by Naro Moru Lodge, offers a substantial dormitory and abundant camping space, thus providing a plethora of options for mountain explorers.

Liki North Hut – 3,993m

Located on the Sirimon Route, the Liki North Hut offers a refuge providing shelter against inclement weather. Able to accommodate eight people and encompassed by a camping area, the hut is conveniently set close to a river for water supply. It can also serve as a starting point for ascending Terere and Sendeyo, or as a stopover on the route to Shipton’s Camp.

Sirimon Bandas – 2,650 m

The Sirimon Bandas, a collection of retreats nestled within Mount Kenya National Park, provide a genuine taste of African wildlife. The bandas comprise two bedrooms, a kitchen, a dining room, a bathroom, and a veranda. Park entrance fees apply here too. A nearby camping area also boasts running water.

Old Moses Camp – 3,400 m

The Old Moses Camp, a campsite on the Sirimon route, is another shelter run by the Mountain Rock Bantu Lodge. Equipped with dormitories, a vast camping area, and accommodation for guides and porters, the camp is a welcome stop for travellers on this route.

Shipton’s Camp – 4,236 metres

Shipton’s Camp, another encampment on the Sirimon route, is a natural marvel not to be missed. Managed by the Mountain Rock Bantu Lodge, this camp is home to a diverse range of wildlife, including numerous rock hyraxes, striped grass mice and various species of sunbirds and wheatear.

Howell Hut – 4,236 metres