In 1979, the indomitable Hannelore Schmatz etched her name in history as the fourth woman to conquer the mighty Mount Everest. Yet, her breathtaking ascent to the roof of the world would, regrettably, be her final adventure.

Passionate German mountaineer Hannelore Schmatz, accompanied by her equally adventurous husband, Gerhard, set out on the boldest expedition of their lives in 1979: to tame the towering Everest.

The intrepid couple triumphantly reached the summit, but their descent proved to be a perilous journey. Schmatz succumbed to the mountain’s wrath in an unfortunate turn of events. As a result, she became the first woman and German national to perish on its treacherous slopes.

For many years, Hannelore Schmatz’s mummified remains, unmistakable with her backpack pressed against her, served as a chilling reminder of the risks faced by those daring to challenge Everest’s unforgiving terrain.

Hannelore Schmatz, an Experienced Climber

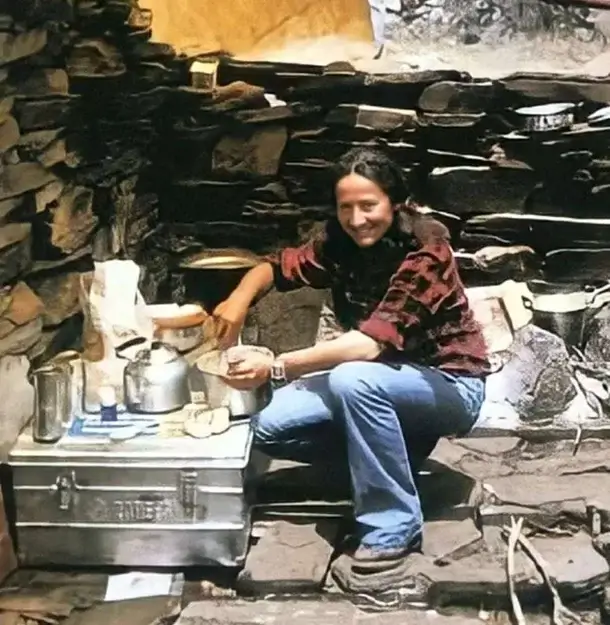

Experienced Himalayan climbers

Venturing into the realm of the mighty Everest is a feat reserved for the most intrepid and seasoned climbers.

Hannelore Schmatz and her husband, Gerhard Schmatz, formed a formidable mountaineering partnership. Because of this, they were fueled by a desire to conquer the world’s most breathtaking summits.

Undaunted and resolute, the husband and wife team set their sights on the ultimate challenge—Mount Everest. They applied for a permit with the Nepalese authorities and embarked on the demanding preparations required to face this supreme test of fortitude.

They bagged a few summits before their Everest expedition

The pair summited a new peak each year to acclimate themselves to the harsh conditions at extreme altitudes. As time passed, the mountains they climbed grew taller. After a successful ascent of Lhotse, the fourth highest peak in the world, in June 1977, they received the thrilling news that their request to climb Everest had been granted.

Hannelore Schmatz had solid expedition preparations skills

Hannelore, praised by her husband for her exceptional ability to organize and procure expedition materials, meticulously managed their Everest adventure’s technical and logistical elements.

During the 1970s, obtaining suitable climbing equipment in Kathmandu was quite challenging.

The necessary gear for their three-month expedition to Everest’s peak had to be sourced from Europe. To accommodate this, Hannelore arranged for a warehouse in Nepal to store several tons of equipment essential for their journey.

Summiting Mount Everest

A group of experienced mountaineers

Hannelore, Gerhard, and Ray Genet were all accomplished mountaineers who had challenged themselves on some of the world’s highest peaks. Together, they embarked on a daring expedition to conquer Everest and return to base camp with their team.

Ray Genet, affectionately known as “Pirate,” was a Swiss-born American mountaineer and the pioneering guide on North America’s tallest peak, Alaska’s Denali (Mount McKinley).

In May 1973, after their successful Manaslu expedition, Gerhard and Hannelore applied for permission to climb Mt. Everest. When their request got accepted by the Nepal Ministry of Foreign Affairs, they started their preparations and training.

Over the next three years, they climbed numerous towering peaks to expand their high-altitude mountaineering skills and experience.

Gerhard, who led the expedition, was 50 years old at the time. He then earnt the distinction of being the oldest person to reach the summit of Everest.

The preparations

The moment they received permission for their Everest quest, Hannelore and Gerhard sprang into action, meticulously preparing for the monumental undertaking.

Hannelore’s exceptional skills in sourcing and transporting expedition materials were crucial during this time. Suitable food and equipment were unavailable in Kathmandu. Everything they and the Sherpas needed for the three-month expedition had to be purchased in Europe and shipped to Nepal.

Resourceful and determined, Hannelore penned hundreds of letters and secured a sponsored truck to transport the gear. With assistance, she spent months packing several tons of materials into 30 kg parcels in a warehouse. She was making sure they were ready for the porters to carry.

A strong team surrounded Hannelore Schmatz

In addition to equipment, the couple needed to assemble a top-notch team of climbers.

Joining Hannelore and Gerhard Schmatz were six other seasoned high-altitude mountaineers:

- New Zealander Nick Banks

- Swiss Hans von Känel

- American Ray Genet—a trusted expert who had climbed with the Schmatzs before

- German climbers Tilman Fischbach, Günter Fights, and Hermann Warth

Hannelore was the sole woman in the group.

By July 1979, all was set for the daring venture. The Schmatz’s Everest expedition consisted of a formidable team of eight climbers. They were supported by five Sherpas who guided them on their ambitious quest.

The 1979 expedition

During their ascent, the team scaled around 24,606 feet (7,500m) above sea level, venturing into the challenging terrain known as “the yellow band.”

To reach the South Col camp, they crossed the treacherous Geneva Spur. It is a sharp-edged ridge connecting Lhotse and Everest at an altitude of 26,200 feet (7,985m). On September 24, 1979, the group elected to establish their final high camp at the South Col.

However, an unexpected, multi-day blizzard forced the entire team to retreat to Camp III. Undeterred, they made another attempt to reach the South Col, this time splitting into two large groups. Hannelore Schmatz joined one group with fellow climbers and two Sherpas, while her husband Gerhard led the other.

After their gruelling three-day climb, Gerhard’s group reached the South Col ahead of the others. Then they set up camp for the night and awaited the arrival of their teammates.

Arriving at the South Col signified a crucial milestone for the team. Travelling in groups of three through the unforgiving mountain landscape, they were now on the brink of the final phase of their ascent to Everest’s summit.

While Hannelore Schmatz’s group continued their trek to the South Col, Gerhard’s team commenced their hike towards the peak early on the morning of October 1, 1979.

Reaching the summit

By 2 p.m., Gerhard’s group had reached the south summit of Mount Everest. At 50 years old, Gerhard Schmatz etched his name in the annals of mountaineering history. He became the oldest person to stand atop the world’s highest peak.

Gerhard observed the perilous conditions spanning from the southern summit to the peak as the group celebrated their triumph. Recognizing the risks, Gerhard’s team swiftly began their descent, facing the same obstacles that had challenged them during the climb.

Upon reaching the South Col camp at 7 p.m. that evening, they found Hannelore’s group—having arrived around the time Gerhard had summited Everest—already preparing their camp for their own ascent to the peak.

Gerhard and his teammates cautioned Hannelore and the others about the treacherous snow and ice conditions. As a result, they urged them to reconsider their climb. However, Hannelore’s determination was unwavering, as her husband described her as “indignant,” resolute in her quest to conquer the mighty Everest.

The Tragic Demise of Hannelore Schmatz

Weary from their arduous ascent, Hannelore Schmatz and another climber found themselves trapped by darkness at 8,300 meters (27,200 feet) just below Everest’s summit. Despite the Sherpas’ insistence that they descend, both Hannelore and American climber Ray Genet chose to rest and never rose again. Hannelore became the first woman to perish on Everest’s upper slopes.

Hannelore successfully reaches the summit

As the first light of day broke, Hannelore Schmatz and her group began their final ascent to the summit of Mount Everest, starting from the South Col point. In the meantime, her husband, Gerhard, began his descent towards Camp III as the weather conditions took a turn for the worse.

As the day progressed, news reached Gerhard via walkie-talkie that his wife and her team had successfully reached the summit of Everest. Hannelore Schmatz had become the fourth woman in history to stand atop the world’s highest peak, marking an impressive achievement for the seasoned mountaineer.

A difficult descent

Tragically, Hannelore’s descent proved perilous. According to her group’s surviving members, Hannelore and Ray Genet were exhausted despite being strong climbers. As night fell, they decided to bivouac at 28,000 feet (8,500 m), disregarding their Sherpa guides’ advice to continue moving.

Hannelore and Genet, determined to stop and set up a bivouac camp (a sheltered outcropping), faced strong opposition from Sherpas Sungdare and Ang Jangbu. They were in the midst of the notorious Death Zone, where perilous conditions leave climbers extremely vulnerable. The Sherpas urged them to press on and make it back to the safer base camp further down the mountain.

An unforgiving zone

Tragically, Ray Genet succumbed to the elements that night. Distraught but determined, Hannelore and the two Sherpas resolved to continue their descent.

However, the unforgiving climate had already taken its toll on Hannelore. At 27,200 feet (8,300 m), an exhausted Schmatz sat down, called for water, and passed away. Sungdare Sherpa, one of the guides, remained with her body, ultimately losing most of his fingers and toes to frostbite.

In the aftermath of this tragedy, Hannelore Schmatz became the first woman and the first German to die on Everest’s treacherous slopes.

Schmatz’s Remains: A Chilling Warning for Fellow Climbers

Ray Genet’s body vanished and has never been found. In contrast, Hannelore Schmatz’s remains were visible for years to those daring to summit Everest via the southern route. Her body, frozen in a seated position, became a macabre landmark just 100 meters above Camp IV. The extreme cold and snow horrifically mummified her remains, with her eyes open and hair blowing in the wind.

Hannelore’s death garnered notoriety among climbers, particularly due to the state of her body, which served as a chilling reminder of Everest’s unforgiving nature. Clad in her climbing gear and clothing, her seemingly peaceful pose led other climbers to refer to her as the “German Woman.”

Norwegian mountaineer and expedition leader Arne Næss Jr., who successfully summited Everest in 1985, recounted his haunting encounter with Hannelore Schmatz’s corpse: the haunting presence of Hannelore Schmatz’s corpse, sitting as if resting above Camp IV, serves as a chilling reminder of the mountain’s unforgiving conditions. Her eyes seem to follow climbers as they pass, reinforcing that they are at the mercy of Everest’s harsh environment.

In 1984, a Sherpa and a Nepalese police inspector attempted to recover Hannelore Schmatz’s body, but tragically, both men fell to their deaths during the effort. Eventually, the mountain claimed Hannelore for good. A powerful gust of wind pushed her body, causing it to tumble over the Kangshung Face, where it disappeared from sight, forever lost to the merciless elements of Mount Everest.

Hannelore Schmatz, a sombre reminder of the perils mountaineers face

Hannelore Schmatz is not the only one on the mountain

Before it disappeared, Hannelore Schmatz’s body was a chilling reminder in the infamous Death Zone, where climbers contend with dangerously thin oxygen levels above 24,000 feet. Many bodies are scattered across Mount Everest, many resting within the perilous Death Zone.

Despite the snow and ice, Everest’s low relative humidity helps preserve these bodies, which now serve as stark warnings to other climbers. Among the most renowned of these bodies—apart from Hannelore’s—is that of George Mallory, who tried to reach the summit in 1924. Climbers stumbled upon his body 75 years later, in 1999.

Throughout the years, Everest has claimed the lives of an estimated 280 climbers. Until 2007, one in every ten adventurers who braved the world’s highest peak never returned to share their tale. The death rate has risen since 2007, exacerbated by an increase in the number of summit attempts.

The general causes of death on Everest

Fatigue is indeed a common cause of death on Mount Everest. Climbers may become too exhausted from the physical strain, lack of oxygen, or excessive energy expenditure to make their way back down the mountain after reaching the summit.

This fatigue can lead to a lack of coordination, confusion, and incoherence. In some cases, the brain may even bleed internally, exacerbating the situation.

Exhaustion and possibly confusion contributed to Hannelore Schmatz’s tragic death. Despite her experience, she chose to rest instead of continuing to the base camp. The decision proved fatal. In the unforgiving Death Zone above 24,000 feet, the mountain ultimately prevails if climbers are too weak to carry on.

Conclusion

For years, Schmatz’s mummified corpse remained visible to climbers on the southern route, a chilling testament to the harsh conditions and the extreme risks involved in scaling the mountain. Her frozen body, sitting against her backpack with eyes open and hair blowing in the wind, became a haunting landmark and a stark warning for those who dared to challenge the mighty Everest.

Although her body eventually disappeared, tumbling over the side of the Kangshung Face, the memory of Hannelore Schmatz’s fate lingers in the minds of climbers and adventure enthusiasts. Her story underscores the importance of respecting the mountain. Understanding one’s limits and making well-informed decisions while navigating the treacherous Death Zone above 24,000 feet (7,500m).

In the end, Hannelore Schmatz’s legacy is a potent reminder of the extreme challenges and potential consequences faced by those who pursue their dreams of conquering Mount Everest.