Ladakh. What a place. I have wanted to go there for a long time, and it did not disappoint. Some of the world’s most spectacular mountain scenery, matched by a Tibetan-flavoured culture, make it a unique place. The whole area is a high-altitude desert and has a good share of Himalayan “big peaks” to play with. And so, with a planned trek through the amazing Markha Valley, it was inevitable that I would look for another 6000m peak to climb. Of course, I do have aspirations for mountains higher than that, but after the success of Island Peak in 2010, I wanted to see if it was just a lucky break or did I have the ability to do it all again?

Two days before the climb, the sky was blue, the weather warm. Kang Yatze sat proudly among the treeless round mountains of the Nimaling area. We had left the jagged spike peaks of the Markha Valley, where we had travelled around 80km over high passes and through arid rugged terrain.

But now, the hills seemed more reminiscent of the Australian Snowy Mountains, complete with granite boulders. But, of course, Australia has no peaks that resemble the glaciated massif of Kang Yatze and its neighbours, so it was still worth being there!

On the way to Nimaling, I noticed a rainbow of ice in the blue skies. This is a strong omen of colder weather ahead. Our guide Namgyal had phoned the HQ of Overland Escape (our trekking company), and the weather was going to include some clouds and maybe snow but clear later. Again, the sky told the story.

Sure enough, the day we arrived at Kang Yatze base camp (5100m), it was snowing all afternoon, apart from a clearing near sunset. Then as I prepared to sleep until my wake-up time of 12.30 am, I could hear the gritty sound of sago snow falling, sometimes as heavy as rain. My heart sank every time I woke up. More snow is falling! I had come all this way to climb a peak, and now it seemed as if it was not going to happen. We would not attempt it if it were snowing heavily.

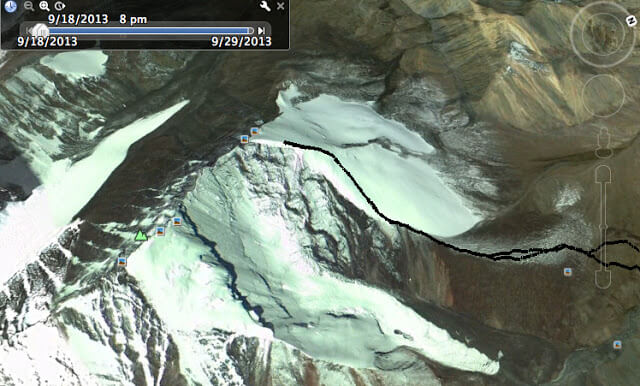

Kang Yatze is made up of several mountains, KY 1 through 4. KY 1 is 6400m and is considered to be quite technical. Therefore, it receives a much lower number of climbers than its shoulder peak KY 2, which comes in between 6200m and 6175m, depending on what maps you refer to! KY 2 is the second point on the right-hand side of the mountain. This is the “trekking peak”, needing only basic alpine techniques to reach the top.

But at 12.30 am, the porridge was cooking, and I sat in the mess tent having an early breakfast. My Nepali climbing guide Nima was confident we were OK to go. And at 1.30 am, we set off into the night, head torches illuminating the falling snow, as we somehow found the stone cairns leading the way up the ridge.

Although I could feel the altitude making the climb harder, I think I felt well acclimatized after trekking for nine days at a high altitude. Of course, it was hard and breathless, but I only had a slight headache, which a Nurofen soon took care of. It must have been cold, as my hydration drinking hose froze, and soon I could not drink. I recall Brigitte Koch-Muir (my guide, mentor and now friend) had warned of this on the Island Peak trek. But I found that if I shoved the hose in my jacket, it thawed in a few minutes, and I soon got the precious flow of water happening again.

Drinking lots of water is crucial at high altitudes.

It seemed like an endless up and endless night, but finally, at a small strand of prayer flags, we were at the “crampon point”. I think the elevation was about 5400m. The sun began to rise amid clouded and misty dawn. Kang Yatze 1 looked down on us with a stern rocky face. Who dares come up to these heights? Its fearsome ice cliffs and broken blocks of ice as big as small buildings showed that despite its size, it could deliver destruction at any time. I now understood its bipolar character. Our side was a huge snow cone, the other side a nasty mix of crevasses, ice cliffs, steep fluted chutes and a knife-edge ridge.

Once the crampons were on my boots, the ascent began. The snow seemed innocent enough at first. Just a big climb up the snow… Nima broke the ground, but I soon found the snow was so loose and fluffy that following steps did not amount to much ease. Every step collapsed, and the climbing began to seem very hard indeed. I had thought I would be going up hard-pack snow like on Island Peak. Usually, this route looks like that (on the YouTube clips I had seen). Hard snow, just a big hill to climb in crampons. Perhaps a bit like when my friend Steve Gottschling and I climbed up Ngaurahoe (2291m, North Island, New Zealand, in a raging blizzard) in 2011. Hard snow that crampons bite into. Not this sugary, loose junk.

Nima looked like he was climbing into space; the sky was a dark blue in this high atmosphere. And the cone of snow loomed higher, and slowly the slope became steeper. The mountain appeared to have no end to its heights. There were times when I had to stop short of Nima by only a few steps to regain my breath and energy. But we pressed on; his Nepalese doggedness to climb ever upward amazed me. These people really are made in the mountains! At least the views were astounding, so at any rest stop, I had time to shoot photos and take in the fantastic views.

Slowly, we neared what appeared to be an increase in the steep slope. Then we started following the edge of the cornice that led to the summit ridge. Nima had said that this section would be more vertical. A complete understatement!

As we inched our way up the steep section, suddenly, I heard a surreal “whoomph!”. Deep and bassy, I had never heard such a sound before. I looked to my left and saw a 20m crack zigzagging its way toward the cornice line. Unfortunately, I didn’t think to take a photo. I just stood there wondering if anything else was going to happen. Finally, Nima calmly said, “The new snow, it causes an avalanche”.

“Good to know,” I thought…

I have since learnt that the sound I heard is a classic avalanche release sound, and upon reflection, it’s very lucky it didn’t let go that day!

Time seemed to escape us. 10m seemed like 100. What looked like it would take 15 mins took 45. The altimeter now showed 5900m then creeping slowly over 6000….

I’m sure the slow progress was my fault, as Nima would just push (seemingly effortlessly) upwards. I struggled along behind him, often taking three steps before bending over my ice axe and gasping. Then with a grunt and groan, I would try and manage a few more steps. It was heartbreaking work, the snow never had any structure, and the ice axe would plunge in and not grip anything. Sometimes the snow seemed wet in appearance, and the ice axe made a metallic squeak as it went in. It would give some hold then, but mostly it was just soft and powdery. Great for skiing and snowshoeing. Not for crampons and axes.

Finally, at about 11.30 am, it looked like we were near the top of the endless slope, yet I felt I had reached my energy limit. After all, I still had to make it down. We had been climbing since 1.30 am. I suggested to Nima that we were high enough. After all, the true summit of KY 1 was not our goal.

The second summit is more of a ridge point, although it still has the highest point on a rocky bluff. We were literally at the most, about 60m below that, at 6140m.

The views were fantastic. At that point, I felt happy, well above my goal of 6000m and with amazing views. I went over to look at KY1s summit, near the cornice line. Just as I approached it, about 10m away, a large section broke off and tumbled into the abyss below. I took the hint and stepped back from the cornice after that!!

We ate some lunch. Well, what I could eat of it since I was almost too exhausted to eat anything. Then photos were taken of the amazing vistas across the Markha Valley, Stok Range and Zanskar Mountains. My prayer flags meant for the summit cairn were laid to rest in the snow. The mountain had given us a pardon and allowed a climb, although Nima confirmed that “normally, people don’t climb here in such deep fresh snow”. Yep…. I had that figured for sure!

But the mountain had also given me a few signs that it held the aces. Even a “trekking peak “deserves respect once it becomes a 6000 m one.

Our descent was uneventful but mesmerizing (perhaps it was the thin air). Snowballs of all shapes and sizes, dislodged by our boots, would hurtle down the steep slope, gaining speed, breaking into two or having erratic paths if they were oddly shaped. It kept me amused on the long walk down anyway.

Namgyal had thoughtfully sent one of the kitchen boys up with juice and biscuits, 300m above the camp (in sneakers). What a welcome sight he was, although when he offered to carry my backpack, I declined. I would rather he carried me!

By4.30 pm we were back at base camp. A 15-hour odyssey. And now I have six times two. Two peaks I have climbed over 6000m. Perhaps now it was time to think about going up a number. 7000m still remains my goal for now…

I played out the climb over and over in my mind like some mental case. Did I have enough to have kept going? Should I have rested and then gone for the summit? We did have enough time, and we could have come down with headlamps if need be. But was it too dangerous?

I am not unhappy about not summiting since I had passed the 6000m line. I just don’t deal well with ‘unfinished business’!

But I won’t do Kang Yatze again, and There is no need.

It was a totally fun and amazing experience, and there are many other peaks yet to be climbed!