Nanga Parbat, or the “Killer Mountain”

The killer mountain

Nanga Parbat, nicknamed “the killer mountain”, is a summit as fascinating as it is formidable. As of July 11, 2009, 322 intrepid climbers, including 22 women, had succeeded in reaching its summit. However, this merciless mountain has also taken the lives of 68 adventurers. This represents c.22% of attempts to date, bringing the tragic toll to 74 climbers by March 2019.

The sinister nickname “killer mountain” was given to it by the German expedition that finally managed to climb its flanks on July 3, 1953, after numerous unsuccessful attempts. Before this victory, thirty-one souls had perished trying to tame this giant of the Himalayas.

Between Albert F. Mummery’s daring first attempt in 1895 and Hermann Buhl’s successful first ascent in 1953, the Nanga Parbat tragically cost the lives of 30 intrepid adventurers. This summit holds a sad record testifying to its danger and the determination of the mountaineers to overcome its challenges.

The majestic Nanga Parbat, towering at an altitude of 8,125 meters, proudly stands as the ninth highest peak in the world and belongs to the famous Himalayan mountain range. Located entirely within Pakistani territory, this iconic mountain is also the westernmost peak over 8,000 meters. Its name, Nanga Parbat, means “naked mountain,” but it is also known as Diamir, which translates to “King of the Mountains,” reflecting its grandeur and majesty.

Many disasters

The legendary mountaineer Mummery was the first to tackle the formidable Nanga Parbat. He was followed by two Austrian-German expeditions in 1934 and 1937, which paid a heavy price to this merciless mountain. With its three immense and complex faces exposed to avalanches, Nanga Parbat presents a real challenge in terms of route.

Contrary to most other peaks over 8,000 meters, there is no obvious route to the summit.

Until the first successful ascent in 1953, mountaineers focused their efforts on the north side and the Rakhiot Glacier. We invite you to relive the tragic and epic moments of Himalayan history, as well as to discover the stories of more recent and contemporary expeditions that have marked the exploration of Nanga Parbat.

Among mountaineers, Nanga Parbat is considered one of the most difficult peaks over 8,000 meters to conquer. Unlike Everest, even the most classic and “easy” route to reach its summit, the Kinshofer route, proves to be extremely difficult. This path features steep slopes, avalanche corridors, and areas exposed to rockfall, making the ascent perilous and pushing climbers to the test of their limits.

Distinctive features

Located at the western end of the Himalayan chain, Nanga Parbat stands out as one of the most imposing and isolated mountain masses on Earth. The altitude difference between the summit and the bottom of the Indus Valley, located only 25 km away, is about 7,000 meters, testifying to its dizzying grandeur.

Moreover, the south wall of Nanga Parbat, also known as the Rupal Face, stands majestically at 4,500 meters, making it the highest rock wall in the world. These exceptional characteristics are sure to inspire respect and fascination among adventurers and mountain lovers.

From a geological standpoint, Nanga Parbat is primarily composed of granites and gneiss, metamorphic rocks that give it a solid and impressive structure. Depending on weather conditions, this composition can sometimes earn it the nickname “blue mountain” due to the hues it emits.

On the climatic level, Nanga Parbat is located at the border between two thermal zones, which causes violent and impetuous winds. These difficult climatic conditions add an extra challenge for the mountaineers who attempt to climb this extraordinary summit.

The macabre history of Nanga Parbat

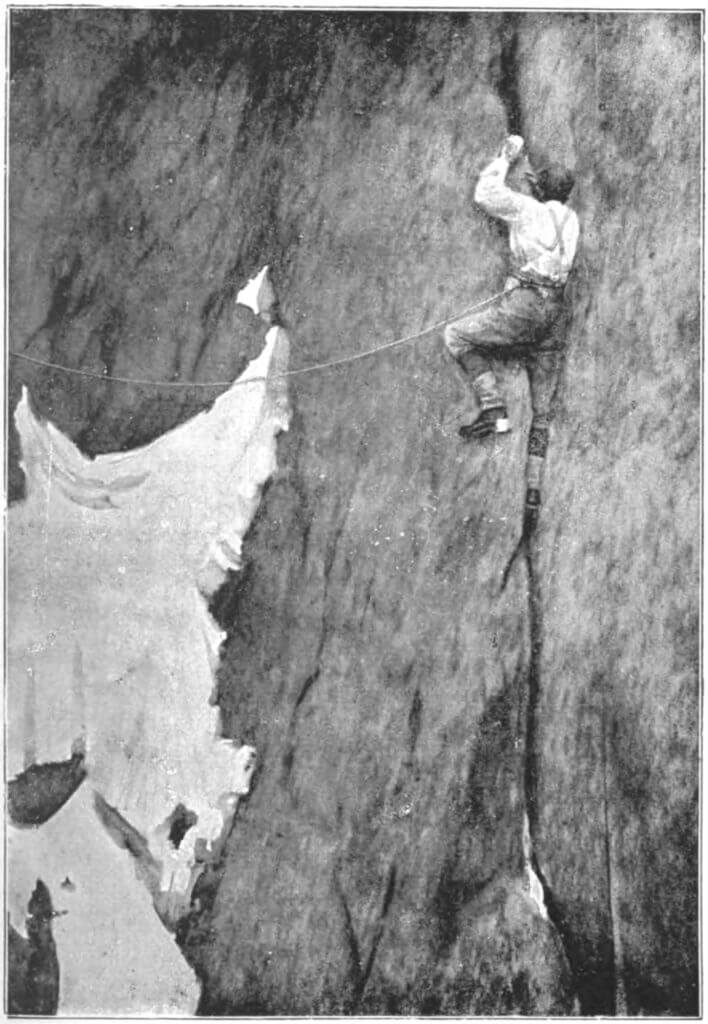

Mummery and the first attempt

The very first attempt to climb Nanga Parbat was made in 1895 by the greatest English mountaineer of the time, Albert F. Mummery. This historic expedition marked the first attempt to climb a peak over 8,000 meters.

Mummery was an experienced climber. He had already accomplished daring ascents, such as the Grépon via the great crack (Mummery crack) and the Matterhorn via the Zmutt ridge.

On August 18, 1895, the first serious attempt of the expedition on Nanga Parbat failed at 6,200 meters altitude. Despite this failure, Mummery refused to make the long detour through the low valleys to return to Kashmir. He then began the ascent by the Diamir side, probably reaching an altitude of about 6,600 meters.

Convinced that a breach at the top of the Diamir Glacier offered a shortcut, Mummery set off on a new attempt with two porters. Alas, they disappeared without a trace and were never seen again. This first tragic expedition highlighted the danger of Nanga Parbat and the merciless challenge it presents to mountaineers.

The early 20th-century German attempts

The first failures

During the 1930s, the German mountaineer Willy Merkl also attempted to conquer the summit of Nanga Parbat. In 1932, he participated in the German-American Himalayan Expedition (Deutsch-amerikanischen Himalaya-Expedition (DAHE)), referred to as a “reconnaissance expedition”, but he also failed to reach the summit.

During the next expedition in 1934, Alfred Drexel succumbed upon the establishment of the base camp. He died of pulmonary oedema. Subsequently, a snowstorm on the southeast wall, at about 7,500 meters altitude, claimed the expedition leader Willy Merkl, Willy Welzenbach and Uli Wieland, as well as six Sherpas. They all perished one after the other.

Following this tragic expedition, the Nazi propaganda press renamed the Nanga Parbat “the mountain of the German destiny” (Schicksalsberg der Deutschen). Despite these failures and losses, Erwin Schneider and Peter Aschenbrenner managed to reach an antecime at 7,895 meters of altitude. It marked a significant advance in the exploration of this formidable mountain.

The Disasters and Failures of 1937 and 1938

Until the late 1930s, Nanga Parbat added many members of the German alpine elite to its grim tally. During the 1937 expedition, no fewer than sixteen people perished in an avalanche, including seven German climbers and nine Sherpas. The following expedition, led by Paul Bauer in 1938, paid increased attention to safety conditions but did not manage to climb the mountain to the altitude reached during the 1934 expedition.

During this expedition, the remains of Willy Merkl and the Sherpa Gay-Lay were found. Gay-Lay, although having the possibility to go back down, had preferred to stay with his sahib. The Nazi propaganda of the time celebrated him as a hero who had bravely faced death.

The 1939 expedition and the beginning of the Second World War

During the summer of 1939, a new exploratory expedition was undertaken on the northwest face of Nanga Parbat, the Diamir face. However, World War II broke out during the return journey of the team, composed of Peter Aufschnaiter, Heinrich Harrer, Lutz Chicken and Hans Lobenhoffer. The participants were interned in the British Indies due to the conflict.

The fate of Harrer and Aufschnaiter was later popularized thanks to Harrer’s book, Seven Years in Tibet, published in the early 1950s. This account, which became world-famous, recounts their adventures from their detention to their escape and journey to Tibet. The book was also adapted into a movie in 1997. It also contributed to the fame of this story of adventure and perseverance.

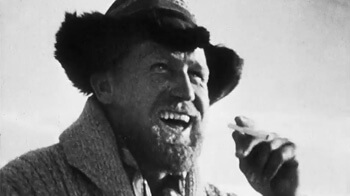

Hermann Buhl and the Post-War Success

After World War II, K. M. Herrligkoffer, half-brother of Willy Merkl, began preparing a new expedition to Nanga Parbat. Despite the thirty-one people who had perished in previous attempts, Austrian climber Hermann Buhl finally reached the summit on July 3, 1953, achieving an exceptional climbing performance.

Buhl began his ascent to the summit from the base camp located at 6,900 meters altitude. He reached the summit without artificial oxygen supply in a record time of 41 hours, considered then as impossible.

This feat was initially met with reluctance by members of the expedition, notably by its organizer Karl-Maria Herrligkoffer, as Buhl had not followed the expedition leader’s instructions. However, the crucial decisions made by Buhl, though contrary to orders, proved to be wise. Today, Buhl’s accomplishments are recognized and celebrated for their true worth as a pioneering act in extreme ascents.

A first by the face of the Diamir

In 1962, the Bavarian mountaineers Toni Kinshofer, Siegfried Löw and Anderl Mannhardt succeeded in climbing the Diamir face for the first time. It also marked the second successful ascent of the summit since Hermann Buhl’s. Unfortunately, the descent cost Siegfried Löw his life, while Kinshofer and Mannhardt returned with severe frostbite.

This expedition was also organized by K. M. Herrligkoffer.

The Messner Expedition, Success and Tragedy

In 1970, Günther and Reinhold Messner succeeded for the first time in climbing the most difficult face of Nanga Parbat, the south face or Rupal side. They climbed without a rope, but the support rope teams following them, being slower, could not catch up. This forced them to descend via the unexplored and unmarked Diamir side, still without a rope or equipment.

According to Reinhold’s accounts, Günther Messner was swept away by an avalanche during the descent. It was not until 2005 that his words were confirmed by the discovery of Günther Messner’s remains. The next day, the Tyrolean Felix Kuen and the Bavarian Peter Scholz also succeeded in the ascent by the south face. However, unlike Reinhold Messner, they descended by the Rupal slope.

This third successful expedition was also led by Herrligkoffer, who organized eight expeditions on this mountain between 1953 and 1975.

In 1978, Messner made a first on Nanga Parbat

In 1978, Reinhold Messner achieved a new ascent of Nanga Parbat and became, on this occasion, the first man to have climbed a summit of 8,000 meters from the base to the summit without interruption.

To accomplish this feat, he took the Diamir side, choosing an unprecedented route both for the ascent and for the descent.

At the base camp, he only had the support of a doctor and a liaison officer.

The Nanga Parbat from the 1980s to the early 2000s.

In 1984, Maurice and Liliane Barrard reached the summit of Nanga Parbat by taking a variant on the Diamir side. They thus achieved the first French ascent and Liliane became the first woman to reach the summit.

In 1990, Hans Kammerlander and Diego Wellig made the first ski descent of Nanga Parbat, taking the Diamir side.

In 2003, Jean-Christophe Lafaille opened a new route on the mountain. He first climbed the first bastion on June 20th and 21st in the company of Italian Simone Moro. However, exhausted at the exit of the route, around 7,000 meters, Moro decided to descend. Jean-Christophe then continued towards the summit by the normal route in the company of his American friend Ed Viesturs. Initially, this new line was to be baptized Tom & Martina (in homage to their respective children), but due to tensions with Moro, Jean-Christophe Lafaille finally only named the route Tom, considering that he had accomplished the ascent alone.

The ascent was completed entirely without oxygen. Back in France, Lafaille declared he never wanted to climb with Moro again.

The most recent ascents and attempts of Nanga Parbat.

In July 2008, the Italian alpinist Karl Unterkircher found death on the Rakhiot wall, at about 6,400 meters of altitude.

On June 22, 2013, the Nanga Parbat massacre took place, in which eleven mountaineers were killed by Pakistani Taliban disguised as Gilgit Scouts at the base camp on the Diamir face.

An expedition composed of Simone Moro (Italy), Alex Txikon (Spain) and Muhammad Ali Sadpara (Pakistan) reached the summit on February 26th, 2016, thus achieving the first winter ascent of Nanga Parbat.

On January 26, 2018, after reaching the summit in alpine style, Polish alpinist Tomasz Mackiewicz and Frenchwoman Élisabeth Revol began their descent. Mackiewicz was suffering from ophthalmia and frostbite, which complicated their progress. The two alpinists eventually separated, and Élisabeth Revol was rescued by a rescue expedition at 6,300 meters altitude. Tomasz Mackiewicz, on the other hand, could not be recovered as planned by helicopter and remained stuck at 7,200 meters. He was declared missing. In March of the following year, British Tom Ballard and Italian Daniele Nardi lost their lives on this mountain.

The main ascent routes of Nanga Parbat

The Rakhiot slope

The Rakhiot side, also known as the “Buhl route,” is the northern route that was taken during the first successful ascent of Nanga Parbat. It is likely the longest and least steep route to reach the summit.

The ascent begins with the Rakhiot Glacier (the base camp in 1953 was located at an altitude of 3,967 meters), located just below the northeast wall. Then, the climbers climb the snow-capped peak of Rakhiot (7,070 m), the Maure Head (Mohrenkopf), and then pass on its eastern slope before reaching the Silver Saddle (Silbersattel), at 7,400 meters altitude.

From there, the route continues on a less steep portion of the Silver Plateau (Silberplateau) before reaching the northern summit. Then, climbers must pass through the Bazhin escarpment (7,812 m) before scaling the final pyramid leading to the summit of Nanga Parbat.

The flank of the Diamir of Nanga Parbat

The Diamir flank, which is the western face of Nanga Parbat, was first taken during the 1962 expedition mentioned earlier (the base camp was at about 4,100 meters altitude). The team did not directly use the “Kinshofer route” (the most frequently used route today), but instead chose a route to the left of the wall. In 1978, Reinhold Messner used a more direct route by taking different tracks on the ascent and descent. Towards the end of the climb, the Diamir route intersects with the other routes on the Bazhin escarpment.

The Diamir face is characterized by a complex network of glacial corridors, huge seracs, and dangerous avalanche chutes. The “Mummery spurs” (Mummery-Rippen) are located halfway up the wall and provide partial protection from avalanches. However, at the base of the spurs, there is an extremely steep and difficult-to-navigate slope.

The Rupal side

The Rupal side, facing south, has an impressive height of 4,500 meters. It is bordered on the right by the spectacular southeast fracture.

The route, first successfully climbed in 1970, follows the steepest area of the ridge line and crosses very difficult sections towards the end, such as the Merkl couloir (Merkl-Rinne) at 7,350 meters and the Welzenbach glacier (Welzenbach-Eisfeld).

An alternative route was taken in 1976 by the reduced expedition led by Hanns Schell, which included four climbers and a doctor. This route went through the left wall, leading them to the southwest ridge, and then finally to the summit after crossing the Mazeno couloir. This “Schell route” is considered to be relatively “easy.”

From September 1st to 8th 2005 (summit on September 6th), Vince Anderson and Steve House (USA) succeeded in the ascent of a new alpine-style route on the central pillar of the Rupal face. This achievement earned them the prestigious Golden Ice Axe (Europe) that year.

The south-east pillars, located to the right of the Direttissima, were first conquered in 1982.

The Diama Glacier

The Diama Glacier, located on the north-west route to the left of the Diamir slope, had not been climbed until 2018. This route was attempted for the first time in 1990 and also by Messner in 2000, but without success. Finally, the summit was reached on January 26, 2018, in winter and alpine style, by Tomasz Mackiewicz and Élisabeth Revol.

Unfortunately, Polish climber Tomasz Mackiewicz perished during the descent attempt, while French climber Élisabeth Revol was rescued by Denis Urubko and Adam Bielecki. Revol suffered multiple frostbites as a result of this expedition.